Almost two weeks ago, I was in Vienna, taking a long walk. Not on the busy shopping boulevards, not around its historical landmarks, but among hundreds of artworks exhibited by more than one hundred galleries under one roof. For the second year, viennacontemporary has gathered artists, art dealers and art collectors at Marx Halle, the freshly reinvented industrial space, situated in the heart of Neu Marx, the district which keeps the heart of Austrian creative and tech industries beating. Viennacontemporary is the largest art fair in the country and the most important event of this kind in the region. Its geographic position is not a coincidence at all, as the fair strongly focuses on promoting art created in Eastern European countries and at the same time on creating and consolidating a market for it. Eastern European arts have not enjoyed their time in the global spotlights, and the social, economic and political context in the region can provide a part of the explanation.

Many galleries in countries belonging to the former so-called "Eastern Bloc", such as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine or Hungary, have been struggling to support contemporary arts in a very fragile world, following the fundamental shifts in the 90s. They had to invent their own rules, to adapt to a system that had been mostly shared by artists approved by the state versus artists working rather as outsiders. They had to plant the very first seeds of a feeble art market in their countries and at the same time connect to the stronger hubs of the European and global art world. Not even now, after more than 25 years of democratic regimes, are contemporary art galleries in this part of the map thriving by all means. As I was speaking to many Eastern European gallery representatives exhibiting at viennacontemporary, most of them were sharing the same version of the story: creating and promoting contemporary art in their homelands often comes hand in hand with mastering the art of survival and perpetual reinventing. No matter how strong the artists' voices may be, having the necessary resources to make them heard is still problematic enough.

This is one of the reasons why an art fair focused on Eastern European art is good news. Step by step, it ensures access of commercial art galleries to a network of collectors and connoiseurs. At the same time, it helps creating a stronger sense of identity for Eastern European artists and their very diversified aesthetic approaches, in the eyes of the global art world. In a moment when living and creating in a former Communist country is no longer exotic, it is time this European countries are known through their contemporary art, which, to some point, creates a challenging scan of their social transformations.

After two days of feeding on the artworkd exhibited at Marx Halle, many of them sharing the minimalist language of conceptualism and formalism, I had the chance to have a brief discussion with Christina Steinbrecher-Pfandt, the artistic director of viennacontemporary. Christina was born in Kazakhstan and, after she studied arts in Great Britain, she started working for major artistic events. She was the artistic director for Art Moscow, an international art fair with already a long tradition, and was a member of the curatorial team for the Moscow Biennale 2009. Since 2014, she has been the sole artistic director of viennacontemporary.

How was working for the Art Moscow fair different from working for viennacontemporary?

Moscow has a completely different focus: while viennacontemporary focuses on Eastern Europe, Moscow focuses on Russia and everything else. The mission of the Moscow fair was to be more international, but without a specific focus, like we have in Vienna.

Are there any specific elements for Eastern-European art?

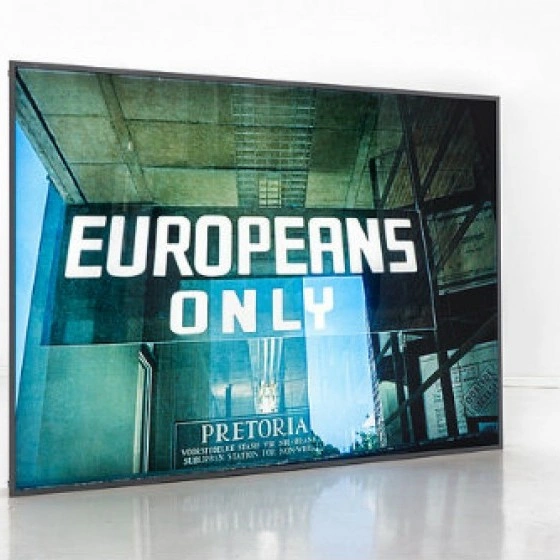

To be honest, if you look at art from the 60s, 70s and 80s, especially at artworks that involve lettering, sometimes you cannot tell apart if it is Western or Eastern. A lot of Eastern European art is now becoming very attractive for Western Europeans, who say Wow, it's of very good quality. They don't need to read a lot of materials to get the whole context they were created in; it is just very good art. Another aspect, related to artworks that comment on the context, on specific political and local issues, does not only apply to Eastern European art. Americans comment on American situations, Africans comment on African situations and so long.

What you mean is that Eastern European art has only lacked a platform, a frame to promote it to a wider audience?

Yes, that's one thing. If you go for creating such a platform, you have to structurally work for it, to make it happen. It's not necessarily a comfortable market and if you do an art fair, not everybody will come your way. You have to do proper research, you have to go out, to motivate people to come, to raise money for projects etc. The market is not rich, so to speak.

I was reading there are 269 art fairs in the world right now and many speak of an "art fair boom". How do you see this?

I think this is now going to be over pretty much. You have to sustain it. Either an art fair creates a working marketplace for the participating galleries - that means they sell - or the market per se has enough money to support itself, and the city that invests in it, to become like a driving force behind it.

So why do you think this boom will soon be over?

Because it was sort of fashionable to start an art fair, but it is actually a lot of hard work and people are just very selective on how they distribute time. The hardest point of having an art fair is actually to create visitors who come annually. You can do an art fair enthusiastically, for one year, but then you actually realize you have to do it again. This is why you have to create mechanisms for them to come back. And this is very difficult.

Is this the most difficult part for you, as an artistic director?

It's one of the difficulties, to create a situation that makes sense for people to return. You have to work with galleries, with the city and its institutions, so that they also create arguments for people to come back.

How do you think the art fair market influences the way artists and galleries work together?

Every gallery that participates is different - this is one thing. Galleries do 6 to 12 shows a year, it depends on their schedule, so the artists deliver to a certain deadline. Some people can deal with deadlines, some people can't do with stress, but that's what it is. Then, if a gallery goes to an art fair, the gallery will think who to bring. That means, they will try to sell and probably select something that they think will sell. That means a certain number of artists will probably not be selected, because they are not suited to that particular area. So only certain number of artists from a particular area will be shown and known in a particular other area. So that area stronger in sales and money will make so that some artists are more famous in that particular area and there will be more demand for that particular artwork and this artist will have to work more in comparison to others.

Speaking of the artworks that are mostly present here, I noticed a lot of minimalist / abstract works. Has this something to do with the collectors' preferences or with the German-Austrian tradition in art?

The reasons why dealers are coming back is an interest in abstract art and painting. They feel more comfortable that they will sell painting, and particularly abstract painting.

How difficult is for you to reach out to collectors?

It's becoming easier, because people have now heard of viennacontemporary. They know Vienna is fun, is a good place, is interesting. It took some time and now we see that the word of mouth is spreading.

Who are the collectors who are hardest to reach, that you would really like to have here?

At some point, you have to be patient with collectors. Because, as a fair, you only open once a year. That's why, some people suddenly can't make it and they can only come next year. This is why you have to be very focused and go for it and understand that if you want some famous person, they will probably be very busy. So you only know that they come when they are really here.