Geta Brătescu is 91 and she is also the first woman artist with a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale, the world’s most important contemporary art event. Romania’s been sending artists at the Biennale for more than 100 years since and this is the first time a woman has been featured with a solo exhibition. „Apariții (Apparitions)”is curated by Magda Radu, and even though it’s only been a month, it is undoubtedly one of this year’s highlights, according to de Telegraph ot the New York Times. I invited Daria Ghiu, author of „În acest pavilion se vede artă. România la Bienala de Artă de la Veneţia (There’s art to be seen in this Pavilion. Romania at the Venice Biennale)” to give us a short tour of Geta Brătescu’s art. You can see Apparitions at the Venice Biennale until November 26.

Before we begin, let’s get acquainted. Geta Brătescu is versatile and mobile. She’s been working relentlessly for over six decades. The joy of art is running through her veins, but she’s hard to pin to an art movement (as she doesn’t like labels). She’s Dada, Neo-Dada, but also Neoavanguardia. She’s for tradition, but also outside of it. She is careful to take the routine out of every piece of object and paper she touches. She’s an intellectual, and a person of culture. She’s challenging through this performative device that she’s able to put into motion, at any time, but she’s not defiant. And she does this, every single day, without fail.

1. Venice, Italy

To paraphrase the title of Geta Brătescu’s first book, published in 1970 at Meridiane Publishing House, let’s start our journey today, From Venice to Venice. The artist went on a trip to Italy with her husband and his best friend, Mihai. It was the middle of the 60s and the journey begun and ended in Venice. Her visit of the city had nothing to do with the Biennale, but with Italy itself. A territory which artists always seem to include in their itinerary, as a vital space to their artistic development. To better understand the context, in 1966 Romanian Pavilion was dedicated to a post-mortem solo exhibition by Ion Țuculescu and was strategically curated by Petru Comarnescu.

“Venice is an empty stage. The modern man, with his simple clothing and unselfconscious manners, floats by this setting that is more suited to brocade and ritualistic gesture” – begins Geta Brătescu’s book. This description of a city that never seems ready for modern times is the way the artist shares her vision of the world with her readers: every space is secretly defined by its traces and routes. She sees all this, intertwined with the present tense, like a predefined memory.

2. The Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

In 1960, some of Geta Brătescu’s pieces were exhibited at the Romanian Pavilion in Venice. It was a collective exhibition by young artists, put together by surrealist Jules Perahim. It joined an exhibition dedicated to the “patriarch” recovered by the new regime, painter Gheorghe Petrașcu. The artist herself did not go to Venice on the occasion, it was only her light pieces that got to go. Among them, Sărbătoare (Celebration), a May 1st defilation, made up of simple and almost abstract lines.

At the age of 91, 57 years later, Geta Brătescu returns to Venice with her work, through a solo exhibition at the Romanian Pavilion. The Venice Biennale is a landmark event in the contemporary art world, and at the moment, the only one which still takes into account the idea of national representation. The presence of Geta Brătescu at the Pavilion is a complete event; the Pavilion was built in 1938 by none other than Nicolae Iorga, a good friend and admirer of Italy and its fascism. In 1929, he created Casa Romen di Venezia, in the Palazzo Correr. The Romanian Pavilion houses the first solo exhibition by a woman. Please keep in mind that our neighbors over at the Polish Pavilion were exhibiting the late Magdalena Abakanowicz in the 1980s. The Romanian Pavilion, located in the Isona Sant’Elena, can be reached either directly, if you are a Romanian and you simply can’t wait to go, or if you come from the Polish Pavilion, which is right next to ours, or even from the Greek one, to our right. Historically, there have been few solo shows at the Romanian Pavilion, and they have all been strictly male. Women artists appear sporadically in collective exhibitions, and are either included in a category that is always of a lesser importance, such as decorative arts (an isolated case in 1970), or graphics (1972). One more thing, women seem to pop up a bit during the interwar period, and also during the socialist realism period.Geta Brătescu is 91 and she is also the first woman artist with a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale, the world’s most important contemporary art event. Romania’s been sending artists at the Biennale for more than 100 years since and this is the first time a woman has been featured with a solo exhibition. „Apariții (Apparitions)”is curated by Magda Radu, and even though it’s only been a month, it is undoubtedly one of this year’s highlights, according to de Telegraph ot the New York Times. I invited Daria Ghiu, author of „În acest pavilion se vede artă. România la Bienala de Artă de la Veneţia (There’s art to be seen in this Pavilion. Romania at the Venice Biennale)” to give us a short tour of Geta Brătescu’s art. You can see Apparitions at the Venice Biennale until November 26.

Before we begin, let’s get acquainted. Geta Brătescu is versatile and mobile. She’s been working relentlessly for over six decades. The joy of art is running through her veins, but she’s hard to pin to an art movement (as she doesn’t like labels). She’s Dada, Neo-Dada, but also Neoavanguardia. She’s for tradition, but also outside of it. She is careful to take the routine out of every piece of object and paper she touches. She’s an intellectual, and a person of culture. She’s challenging through this performative device that she’s able to put into motion, at any time, but she’s not defiant. And she does this, every single day, without fail.

1. Venice, Italy

To paraphrase the title of Geta Brătescu’s first book, published in 1970 at Meridiane Publishing House, let’s start our journey today, From Venice to Venice. The artist went on a trip to Italy with her husband and his best friend, Mihai. It was the middle of the 60s and the journey begun and ended in Venice. Her visit of the city had nothing to do with the Biennale, but with Italy itself. A territory which artists always seem to include in their itinerary, as a vital space to their artistic development. To better understand the context, in 1966 Romanian Pavilion was dedicated to a post-mortem solo exhibition by Ion Țuculescu and was strategically curated by Petru Comarnescu.

“Venice is an empty stage. The modern man, with his simple clothing and unselfconscious manners, floats by this setting that is more suited to brocade and ritualistic gesture” – begins Geta Brătescu’s book. This description of a city that never seems ready for modern times is the way the artist shares her vision of the world with her readers: every space is secretly defined by its traces and routes. She sees all this, intertwined with the present tense, like a predefined memory.

2. The Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

In 1960, some of Geta Brătescu’s pieces were exhibited at the Romanian Pavilion in Venice. It was a collective exhibition by young artists, put together by surrealist Jules Perahim. It joined an exhibition dedicated to the “patriarch” recovered by the new regime, painter Gheorghe Petrașcu. The artist herself did not go to Venice on the occasion, it was only her light pieces that got to go. Among them, Sărbătoare (Celebration), a May 1st defilation, made up of simple and almost abstract lines.

At the age of 91, 57 years later, Geta Brătescu returns to Venice with her work, through a solo exhibition at the Romanian Pavilion. The Venice Biennale is a landmark event in the contemporary art world, and at the moment, the only one which still takes into account the idea of national representation. The presence of Geta Brătescu at the Pavilion is a complete event; the Pavilion was built in 1938 by none other than Nicolae Iorga, a good friend and admirer of Italy and its fascism. In 1929, he created Casa Romen di Venezia, in the Palazzo Correr. The Romanian Pavilion houses the first solo exhibition by a woman. Please keep in mind that our neighbors over at the Polish Pavilion were exhibiting the late Magdalena Abakanowicz in the 1980s. The Romanian Pavilion, located in the Isona Sant’Elena, can be reached either directly, if you are a Romanian and you simply can’t wait to go, or if you come from the Polish Pavilion, which is right next to ours, or even from the Greek one, to our right. Historically, there have been few solo shows at the Romanian Pavilion, and they have all been strictly male. Women artists appear sporadically in collective exhibitions, and are either included in a category that is always of a lesser importance, such as decorative arts (an isolated case in 1970), or graphics (1972). One more thing, women seem to pop up a bit during the interwar period, and also during the socialist realism period.

3. Apparitions

This is the title of Geta Brătescu’s exhibition at the Romanian Pavilion and the Romanian Institute of Culture and Humanistic Research. The exhibition is curated by Magda Radu (author of various studies on Geta Brătescu and curator of a 2012 exhibition entitled Atelierele artistului (The Artist’s Studios), at the Salonul de Proiecte (Show Projects) in Bucharest. The curator had many reasons to choose this title; it’s the title of a series of works that were partially done with the eyes closed: it’s a possible definition of Geta Brătescu’s artistic practice; it works towards the importance that the artists gives to the “spirit” of the work, not the technique (the artistic object as a dance of the mind); it’s absolute freedom, above and beyond social and political constraints; and as Magda Radu called it, it’s an epiphany, the transfiguration of the simple object into an expressive element.

4. The Artist and her studio. Drawing. Politics. „The exquisite sense of space”

The Vagabond Studio or the Continuous Studio: these are the titles of some of Geta Brătescu’s books. Since the 60s, the artist can be found inside an eternal mental studio, but also in a space as concrete as can be, her own studio. Geta Brătescu was born in 1926 in Ploiești. She studied Letters and Belle Arte in Bucharest, and her teachers included Camil Ressu, but also G. Călinescu and Tudor Vianu. On top of her artistic work, she writes a lot. Her books are a blend of journals, novels and short stories. Actually, inside every book she publishes, she writes about art and when she doesn’t, she still expresses her fondness for the visual through the way she perceives the thing around her. “Everything contracts, and reduces when a space is crossed. The crossing of a space is done with a line”, the artist confessed to me during a recent interview, published in Dilema Veche.

The editors of the artist’s Biennale catalogue, Magda Radu and Diana Ursan had a very good idea. The book is constructed around fragments of Geta Brătescu’s books, translated in English: De la Veneția la Veneția (From Venice to Venice), Atelier Continuu (Continous Studio), Atelier Vagabond (Vagabond Studio), A.R.: Roman, Copacul din curtea vecină (The Tree from the Yard Next Door), and Jurnal în Zigzag (Zigzag Journal). It is illustrated with the artist’s pieces, and sprinkled with the two the authors’ analyses. In 1985’s Atelier Continuu (Continous Studio), Geta Brătescu talks about the Proustian universe and about tactility; about Proust’s world as a world full of shapes and colors, a traversed world. A workd that is just just merely seen, where space and the objects are “experienced”. This experience, of traversing the space with your eyes, and this “tactility” of the brain seem crucial for an artist who draws, creates collages, does lithography, tapestry (or as she calls them, “sewing machine drawings”), photography, video works, experimental movies, who creates objects, or works inside the generous space of performance art. All this back and forth from one medium to another, this extraordinary mobility is what characterizes Geta Brătescu. The artist suggests that everything can be reduced to a single medium: drawing. To add to this, in her writings, the artist talks about a “clean” line, direct and without useless shades. About the lack of importance of trying to describe things through drawing, and about the necessity of inventing shapes for various states.

In the Romanian Pavilion, the importance of the studio is crucial to the curatorial discourse. We go inside the pavilion and we find ourselves in front of a large wall that takes advantage of the almost overwhelming height of the building. A wall with recent collages and drawings, that recreates the visual experience from inside the artist’s studio. Pieces born out of the movement and the scissors’ game, precise and colorful shapes, that seem to be the result of pure hazard, and unsullied choreographies. In the same Venice space, somewhere to the right, you can see the 1977 experimental movie Atelierul (The Studio): filled with ritualistic gestures that the artist performs inside the studio space, an attention to script, and an apparent spontaneity.

On the other side, the studio resides inside the mind: Geta Brătescu often states that no matter where she is, she is capable to recreate this imaginary space, that opens her door to freedom, thus making room for artistic autonomy and political uninvolvement. The series of works, Regula cercului (The Rule of the Circle), and Regula jocului (The Rule of the Game) (1982-85), is the clear result that was born out of a given theme (a visit to an industrial place, the cauldron room or the typography) and its result: drawing, abstract collage, the chance to reflect upon the circle and its constraints.

The physical place of the studio is present to an almost obsessive degree in some of her works. It merges with the interior space, which produces worlds and mythologies. The artist confesses that she was blessed with an “exquisite sense of space”.

5. Geta Brătescu self portrait

The artist is often present in her work, but as an object of her own art, consciously excluding the subjectivity. This can be seen at the Romanian Pavilion, in a series of works. We can see her hands working, in Linia (The Line), a video piece from 2014. It is placed at the entrance opening the exhibition, to help people understand about the way the lines “materialize” on the white piece of paper. We can see the exploration of her hands in a series of drawings, Mâini (Hands), 1974-1976; her old feet in a series of photographs from 2009; her multiplied eyes in Autoportret in oglindă (Self Portrait in the Mirror) (2001), a mirror on which there are the artist’s two pairs of eyes, her nose and mouth. The eyes are not watching me, the observer, but they are seeing beyond me, somewhere inside the artist. Instead of cheeks, the audience sees itself reflected in the loose mirror fragments, in a continuous staring game. In the series of photographs Alteritate (Alterity) (2002-2011), Brătescu is dressed in black and wearing white gloves. She stands in front of the lens, covers one eye, and then the other, then her whole face. She then hides herself altogether inside her black clothes, allowing the arms of a gym object to be seen, such a strange appearance. In the last photograph, the artist has her back to us, and is looking at the white wall.

6. Mythology. The territory of femininity, alter-egos

When the artist excludes herself from her work, she creates various feminine shapes. The series Femei (Women) (2007) is a collage of 200 small drawings, executed with the eyes closed. A multitude of small shots, created from fragile and shaky lines. Or the triptic Mame (Mothers) (1997) and the 1965’s Mutter Courage. One particular case is Portretele Medeeei (Medeea’s Portraits) (1979) and in general, all of her interest in Medea, which shines through her drawings, lithography or tapestry. Same with her continuous search for the Mediterranean space. When the artist is absent, and the delicacy of her lines makes room for hesitation, and the space allows itself to be possessed.

7. Faustus

Geta Brătescu is an extraordinary illustrator. We simply cannot fail to mention her presence as an artistic director to the editorial team of magazine Secolul XX (XX Century), nowadays Secolul 21 (21st Century). The magazine was created in 1961 and it has always been considered a breath of fresh air and freedom. In 1969, Ștefan Augustin Doinaș joined the team. At the center of the Romanian Pavilion, are her original illustrations for Faustus (31 drawings, watercolor, and paper collage, 1981-1982), which belong now to the Romanian National Art Museum. Faustus was translated by Doinaș. Every single image attains the statute of sign, as the artist invents a perfect Goethean alphabet, purely conceptual. It’s ironic that Faust is now as contemporary as ever and it’s also the core of the German Pavilion, the winner of the Golden Lion at this year’s Biennale.

8. Memory

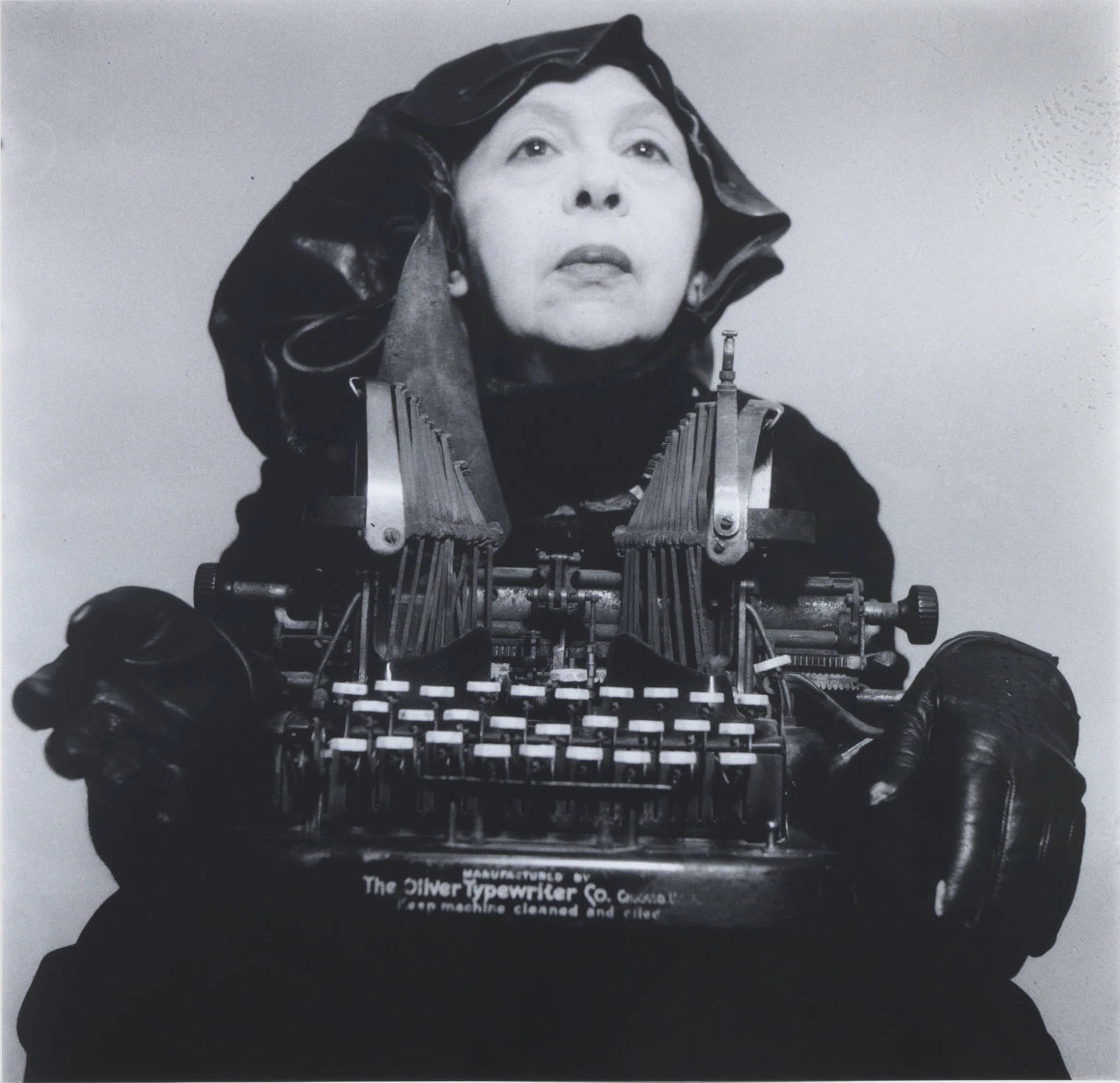

Everything is concerned with question of memory: objects from her and her mother’s childhood, (the typewriter from the photograph Mrs. Oliver in Traveling Costume, an alter-ego of the artist), her father’s glasses, her mother’s colorful patches that become her daughter’s collages (Vestigii (Vestiges), 1978) – memory fragments simply melt into her art. The memory’s total body of work bears this exact name: Memorie (Memory) (1990), and it is also exhibited in Venice: 40 paper collages, black paper on black paper, carefully folded, until it produces soft folds, the same way memory digs trenches in our brains.

9. The hand that draws “under the empire of the line”

Drawing is dancing – the artist has said time and time again. You need to invoke drawing. Drawing is writing, “I believe that drawing is made to be the most provocative means of expression by the line, its primary method of communication”, writes the artist in the 2012 Jurnal în zigzag (Zigzag Journal). Once the lines are out, playing on the white piece of paper, “they are no longer subdued, they ask the right to their individual life, with slim and thick characteristics that suit them”, she writes in the same journal. And: “the hand is free, it dances, it helps itself with slim ruler whenever it feels the need for it; then it launches itself in the pleasure of the arc of a circle.” Drawing and line become poems from the artist’s hands. “I continue to be under the empire of the LINE”, she writes somewhere else, making the distinction between her, a woman with “reduced powers”, and the man who has the capacity to become author of monumental works.

Main photo: Detail from the video piecee „Linia” (The Line). Image, sound, editing: Ștefan Sava. The artist was kind enough to share it with us.

More information and images with Geta Brătescu’s works can be found on the official webpage of “Apparitions”.

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea

For more fresh English-language cultural journalism, brought to you by the new voices of Romania, look here.