(The original version of this article was published in Romanian on November 6, 2018. The current English version has been lightly edited in general accordance with new data issued ever since. An update on the recent actions of the Romanian Ministry of Health regarding the topic of the HPV vaccine has also been added into the text.)

When you do a Google search for “I got the HPV vaccine” in Romanian, you find no results written in the first person.

That may be because, over a decade ago, the Romanian state failed to carry out its only national campaign for vaccination against HPV and cervical cancer. And that may be because little is done to stop a virus which has been striking a more devastating blow in our country than anywhere else in Europe. Romania has had the continent’s highest rate of illness and death due to cervical cancer for decades.

In the summer of 2018, I also failed when I tried to get the vaccine. Here, I’ll be talking in the first person about how I and the country I live in botched, together and in our own way, the same vaccine.

One winter evening, I had a Tinder date with a guy who happened to tell me that he had HPV. My only reaction was a secret sense of safety, as I didn’t really like him anyway.

We were in Rosetti Square, sitting at a wooden table in a piano bar with high windows, the wind slipping like threads of spaghetti beneath them. We drank wine from small glasses, the bottoms of which would stick for a moment to the table every time we picked them up, like we were pulling out staples. He spoke quietly and challenged every sentence out of my mouth. When he went out to smoke and asked if I wanted to join him, I said I don’t like cigarette smoke and that’s it. That’s how little interested I was in him.

We started talking about HPV as if it were a joke about Michael Douglas, who’d got throat cancer because of it. I don’t remember who brought it up, but I remember there were his words and my cowardice—because it seemed like the anecdote had become too human, too personal, too fast—and I headed straight for something theoretical, saying, “that’s just the way it is, everyone has HPV”. And I drank my wine, satisfied with that compound word—every and one— always accompanied by the silent but-not-me of the person using it.

*

HPV is one of the most wide-spread sexually transmitted infections in the world. At that date in the piano bar, I’m not sure if I didn’t know, didn’t want to accept, or I just didn’t want to face this truth.

You don’t have to search Google much to come to the official statements. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “80% of people will get an HPV infection in their lifetime.” The World Health Organization (WHO) points out that “[m]ost sexually active women and men will be infected [with HPV] at some point in their lives and some may be repeatedly infected.” HPV is so common that it is nearly as universal as feelings.

HPV is not HIV or herpes or hepatitis. HPV stands for human papillomavirus and its beautiful molecule looks like flowers or stars strewn over a sphere. It is the cause of 99% of cervical cancer cases worldwide. Without HPV, according to the WHO, cervical cancer would be nearly nonexistent. The researcher who proved this, Harald zur Hausen, won a Nobel in 2008 for his discovery.

After breast cancer, the most common form of cancer for women in Romania between the ages of 15 and 44 is cervical cancer. At nearly three times the average in Europe, our rate of cervical cancer has simply catapulted us to the top on the continent.

HPV exists in the vagina, on the cervix, on the tip of the penis, in the anus, in the mouth, in the throat—which is to say in the mucous. Also, on the skin. It is transmitted horizontally through any kind of sexual contact, but also skin to skin contact which is why condoms don’t always protect against it. It is also transmitted vertically from mother to fetus. Some studies claim that it may also be picked up from surgical gloves and medical instruments.

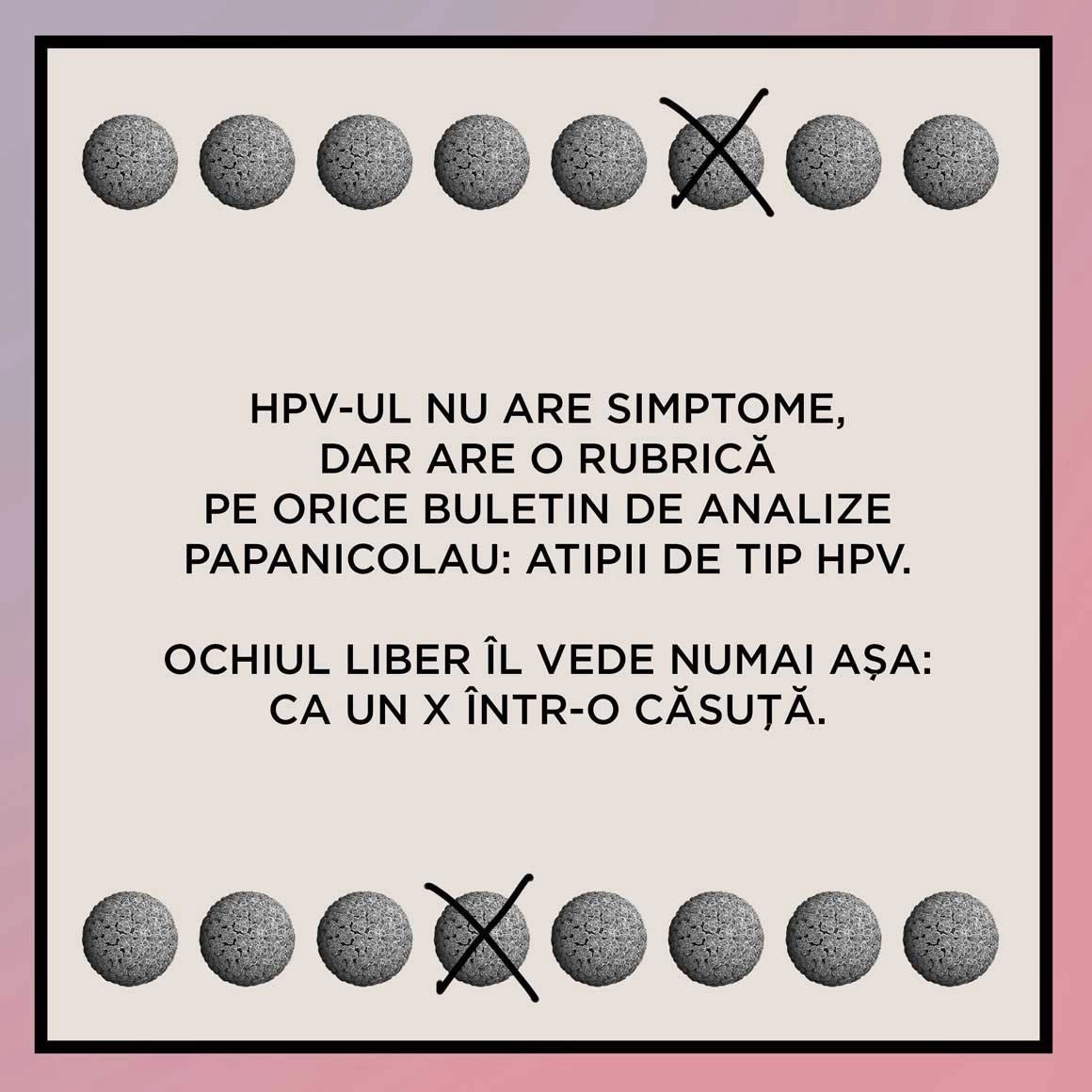

HPV has no symptoms, but it does appear as a line item on Papanicolaou test results around the world as HPV Atypia, represented by an X in a box.

There are nearly 200 identified strains of HPV, but the worst of them are strains 16 and 18. They are solely responsible for 70% of cervical cancer cases and they can cause various other cancers for both sexes: anal, oral, throat, tonsil and tongue. Beyond them, another 10 strains are considered high-risk, or cancerous. 40 others can produce skin warts or a recurrent respiratory tract papilloma, a disease which covers the larynx in small polyps and blocks breathing. The remaining strains are relatively innocuous, but HPV continues to be a sufficiently multifaceted virus.

The good news is that, in general, the body can eliminate the virus within 1-2 years of infection, and only the persistent infections are problematic. The bad news is that, over a lifetime, you can catch the same strain multiple times, and you can have multiple strains at the same time. Fortunately, the lesions which lead to cervical cancer develop slowly, over 10 to 15 years, and the disease can be detected and prevented with regular Papanicolaou tests. In Romania, however, only around 8% of the female population has had a PAP. The other kinds of HPV infections, such as an oral infection, are rarely detected before the cancer stage.

*

There was a moment in the piano bar when I came to fully believe that the guy across the table simply wanted me to understand that he had HPV. Looking back, I can’t explain it, but I knew that this confession on fear and illness had managed to come through to me, to cross the boundary between us which was represented by a sticky table and two glasses of wine. My current granular memory doesn’t help. Nor does the unease I had back then.

I think I remember that he was going on about Michael Douglas and he told me it wasn’t a joke. A few weeks before he was admitted to an ENT section for a few days, in a room with several other men. He had a sinus infection, they had throat cancer. I imagined how he’d have looked at them, having read a study that HPV, not smoking, is the leading cause of throat cancer. Then he gave me a strange look of anticipation as he started a sentence which ended in a plea, his voice growing even softer than before: “I got scared, you can imagine.”

I nodded, but I couldn’t imagine it.

I couldn’t imagine it when we’d gone from being on the defensive to confessing. I couldn’t imagine the specter of a contagion there, between us, the shadow that closeness between any two people can bring about. I couldn’t imagine that now, beyond a medical perspective, an emotional one was needed, and that the binary language of dating which I’d been practicing for years—seduction or unresponsiveness—would ruin any such chance. I couldn’t imagine how the fear of illness involves not only a realistic self-evaluation, but also a declaration of belonging to the world, involves you saying: I’m like all of you, more vulnerable than I’d like to be.

When I got home, on my phone screen there were three text bubbles, like the last breath under water. All from him: I liked our discussion. / Especially the part about HPV. / It was intense.

The only thing I remembered feeling intense about that night was my desire to go home and go to bed. I went to sleep without writing back.

*

After not writing back to him, I was left with a nagging thought: but what if I had liked him? I didn’t know the answer because I’d never thought about it, because up until then, I’d never spoken about HPV at any of the interesting dates I’d been on. Come to think of it, I’d never spoken about HPV on any date.I’d gone out with a man who was closed-off to my ideas and open about his illness, and because I didn’t understand and I didn’t like this kind of interchange—the opposite of what I’d come across until then—I took the liberty of sweeping any decorum of social responsibility under the rug.

I was starting to believe that the reason everyone remained silent about this virus which everyone had was because no one had an antidote. And at this thought, I began to despair.

In her book, On Immunity, American author Eula Biss observes that, since the natural and social sciences began to conceive of the human body as a complex system within other larger systems, people began to feel an overwhelming sense of responsibility for their own health. Biss quotes anthropologist Emily Martin: “The first consequence might be described as the paradox of feeling responsible for everything and powerless at the same time, a kind of empowered powerlessness.” You are just a body dependent on other bodies. Like in a democracy, says Biss.

My empowered powerlessness as concerns HPV was the threat of an invisible thing materialized only by shreds of information and underscored by two beliefs. One was the fact—unverified, but inarguable—that I don’t have the disease. The second followed the first, and it was the vaguely articulated idea that, being exceptionally healthy, everyone around me was exceptionally responsible for keeping me that way—me, more so than anyone else. The fact that, up until then, nobody had made an antidote for HPV, to me was a personal insult on the part of science, intentional negligence.

*

It’s true that, today, there is no antidote for HPV—a medication which, once in the body, would eradicate the virus—but there is a gatekeeper, preventing it from entering: the vaccine.

The first HPV vaccine was invented by two researchers from The University of Queensland, Australia, and it appeared on the market in 2006 under the name Gardasil. Gardasil is tetravalent, meaning it protects against four threads: 16 and 18 (the most likely to cause cancer) and 6 and 11 (the most likely to cause skin warts). It was manufactured by the American company Merck, known in Europe as Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), and was approved in 2006 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the federal agency for medicine in America. One year later, in 2007, the FDA would also approve the vaccine Cervarix, produced by a competitor on the market, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Cervarix was bivalent, protecting only against 16 and 18.

Dozens of countries quickly included one of the two vaccines in their national immunization program. Between 2008 and 2010, Romania attempted a campaign to do just that, purchasing 330,000 vaccines. The Ministry of Health initiative then brought on a maelstrom of accusations, ranging from the suspicion that the vaccine was insufficiently tested, to the fear of adverse effects, to the speculation that the whole program was a big pharma experiment on the local population. In the first year, only 2.5% of the targeted population’s families accepted immunization, and between 2010 and 2011 the Romanian state began destroying the vaccines they’d purchased because they were beginning to expire.

Since then—I’ve been told by Health officials the ministry has stopped purchasing either kind of HPV vaccine for a whole 12 years. (Update, March 4, 2020: In January of 2020, the Romanian Government has eventually purchased a first batch of 20,000 shots of HPV-vaccine aimed at immunizing cca 10,000 girls. Nevertheless, the real need for the vaccine remains widely unprovided for, as roughly around 500,000 people are comprised in the cohort officially eligible for vaccination -- girls aged 11 to 14.)

In contrast, Australia has become a superstar in the fight against HPV. And not only because the inventors of the vaccine originated from there. The legend goes that Australia was the first country to implement nationwide HPV immunization in 2007. (Although, in Europe, Austria had done it in 2006.) At first, the Australian program included only girls, but as the virus continued to grow in the male population, the program expanded in 2013 to include boys. Today, any person in Australia under the age of 19 can benefit from free HPV immunization.

A WHO report shows that, in 2013, 47 countries around the world had already included the HPV vaccine in their national immunization programs: Western European and North American countries, but also Bhutan, Rwanda and Uganda, to name a few. Romania, however, to this day is failing to provide an encompassing HPV-vaccination program for its eligible population.

*

In March 2018, an article from The Guardian popped up on my Facebook feed. It was a photograph of a syringe over a pink, phosphorescent ball, like a rocket about to enter the earth’s atmosphere. Underneath, the title of the article announced that “Australia could become first country to eradicate cervical cancer”. According to the article, a recent study shows that the rate of HPV infections in Australia among people of 24 years or younger has dropped from 22% to 1% and forecasts that, in 40 years, the number of cervical cancer cases in the country will be nearly 0. One specialist states that there are many women in the world, however, who do not have access to the same treatments as the women in Australia. He concludes that, “[u]nless we do something, it will still be one of the major cancer killers in developing countries.”

I was so dumbfounded that I’d forgotten to go back to the post and like it. I was just staring at the photograph at the top of the page—not at the round purple virus on the black background, but at the syringe in the front, in the foreground. So, it wasn’t an experiment. So, maybe science wasn’t exceptionally negligent. And I wasn’t exceptionally healthy, just exceptionally uninformed.

And then I decided to seek out the vaccine and take it.

*

When I asked my gynecologist if it would be too late for me to take the vaccine, she shook her head no. Back in 2018, the Romania prospectus stated: “[t]he safety and efficacy of Gardasil 9 in women of 27 years and over was not studied”.

I’d turned 27 a few days prior. My gynecologist took it at 33, and her friend at 40. She told me, “that’s how it is. You take it when… you hear about it”.

The words “when it’s invented” were stuck in my throat: I was unable to notice the chasm between innovation and information.

I was used to casually bearing the traces of preventive medicine established over half a century ago—the mark on my arm from childhood vaccines which my parents and grandparents also have, a lean neck from a potassium iodide pill against endemic goiter. I had never been told about the devastation of any epidemic, or the hysteria following a new antidote. I’d been living in a period of medical repose, which was just another word for stagnation.

*

That same month, March 2018, when I’d also read the article in The Guardian about Australia’s achievement, a new Gardasil vaccine was being introduced in Romania which protected against nine strains of HPV, whereas the first protected against four. Gardasil 9 had been approved by the FDA in the US in 2014 and, in the EU, by the European Medicines Agency, in 2015.

In a video at its launch in Bucharest, in a green room at the Matei Balș Institute of Infectious Diseases, a few experts in Romanian medicine hold a panel and get behind the idea that everyone should be concerned about cervical cancer.

“It’s a public health issue,” says Alexandru Rafila, the president of the Romanian Society for Microbiology and professor at the Carol Davila University. Adrian Streinu-Cercel, the manager of the institute, adds “and when we say it’s a public health issue, it has been made a priority. Period.” “What’s most important is that we’re talking about the issue,” says Gindrovel Dumitra, the group coordinator of immunization at the National Society of Family Medicine.

Journalists ask questions. When will we see a coherent and sustained informational campaign about the HPV vaccine? Rafila says that the vaccination law needs to be passed. Corneliu Buicu, then president of the Chamber of Deputies’ Committee for Health, struggles to explain why we don’t have health education in schools. Slowly but surely, the discussion slides into tabloid news platitudes. There are schools that still don’t have a bathroom. At others, kids have to walk whole kilometers to get there. Words are repeated: “material resources,” “human resources.” Coordination. Streinu-Cercel cleans his fingernails. The general manager of MSD Romania calmly and gracefully looks to the audience. Dumitra and Buican scroll on their phones. Adriana Pistol, director of the National Center for Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases, tells a joke about a German standing in a line.

A man in the room wants more concrete information about the vaccine: How much does it cost? Rafila and Cercel are given the floor. The first says he doesn’t know, mumbles a bit, then says it will only appear on the market in April. The second shrugs and shuffles with a folder on the table. A woman in the first row in a little black dress and a honey-colored bob gets up out of her chair and whispers to Cercel: 625 lei. Cercel declares, “this just in: 625 RON.” He laughs. The other speakers in the panel laugh, too. It’s funny.

*

When I heard how much the vaccine costs, I wasn’t laughing. Not to mention that I need three vaccinations. My monthly rent is only slightly more expensive than a Gardasil 9 vaccine. For many of us, this comparison sounds less coincidental and more conflicting. It seems like you have to choose between paying to live in a body and paying to live in a home, because the price of a body in a home is too expensive.

Nor was I laughing when my family doctor told me that she can’t give me the vaccination. Her office is part of a private clinic in Pipera with potted orchids at reception and the smell of coffee in the air. Their internal policy there is not to inject vaccines coming from outside the clinic. Ok, but can I order it through the clinic? She said she’ll ask but doesn’t think so. Then she put me through a series of cyclical, discouraging arguments: I need a recommendation from a gynecologist; actually, the gynecologist should give me the vaccine; anyway, if I order it from their clinic, I should expect it to cost MUCH more than from the pharmacies.

I started calling all the private clinics I knew of to ask if they can give me the vaccine. Some responses were direct refusals, others were, initially, confusion—“so, which vaccine?”, “for a baby?”—and then refusal. The only call-center to accept was also the only one to understand from the beginning. I was twice put on hold while they checked with their supervisor, listening to a piano jingle. In the end, they told me to bring the vaccine and a written recommendation from the doctor and they gave me the address and their opening hours.

My family doctor also agreed to finally give me a prescription for the vaccine to show the other clinic, as a recommendation. I asked her if she had other patients who took the vaccine. “No. You’re the first,” she said. That’s how I came to see through her words to a fear of the unknown, like looking through windows.

*

In On Immunity, Eula Biss writes, “[t]he natural body meets the body politic in the act of vaccination, where a single needle penetrates both.” But the natural body and the body politic do not meet only through the needle that penetrates, but also through those vials whose contents are held captive inside. In 2011, the Romanian state had to destroy 95,000 expired HPV vaccines following the failed national vaccination campaign. It is difficult to ignore the weight of this act: a state actor destroying the chance to immunize a demographic. So, too, is the habit which fell involuntarily to all of these small vials of vaccine: better keep it outside the body.

The first HPV vaccination campaign in Romania began in 2008, the same year as in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. In other European countries—such as Austria, Germany, the United Kingdom, France—it was already included in the national immunization program one or two years earlier.

Following the HPV immunization book, the vaccine should: a) be taken in three doses of the vaccine over the course of a year; b) be taken before becoming sexually active, before you can catch the virus. The recommended age is between 9 and 15, because that’s when most antibodies are produced. Therefore, in 2008, the Ministry of Health set out to immunize a group between of 10- and 11-year-old girls. This meant a cohort of 103,000 girls for whom the ministry purchased 330,000 vaccines. The state signed contracts with both pharmaceutical companies—MSD, the producer of Gardasil, and GSK, the producer of Cervarix—purchasing half of the total number of vaccines from each brand. The final cost was 23 million Euro—an apparently advantageous figure, considering that the state was then paying around 70 million Euro for cervical cancer care.

The vaccine was free, it could be taken with the school nurse, and the parents who were for the vaccination needed to give their approval in writing (opt in).

The vaccination campaign began on a Monday, November 24, without any prior public information campaign. On Sunday that same week, there were parliamentary elections—the first since 1990 to not use a list of candidates, but an uninominal ballot. In just a week, many people were forced to consider some major decisions: on a new vaccine and on a new voting system; on a brand for their children’s health and on a political representative.

Meanwhile, there wasn’t even much consensus in the Romanian medical world. In fact, the positions of the thought-leaders were contradictory. For example, Geza Molnar, then the president of the Romanian Society of Epidemiology and a revered giant in the field, declared that if he’d had a daughter or granddaughter in 4th grade, he’d refuse to get her the vaccine. Streinu-Cercel, who was already the manager at Balș and an ambassador of the vaccine, declared, “for the time being, the discovery of the correlation between HPV and cervical cancer was awarded the Nobel. There is nothing else to add.” Molnar was less incisive: “we are addressing a population in which 80% of the people have no idea what this vaccine is or what human papillomavirus is.”

The end result of that week in November 2008, laden with choices, was: a) only 2.57% of parents agreed to vaccinate their kids; b) Emil Boc was named prime minister. In December 2008, the vaccination campaign was called off.

A month later, in January 2009, Ioan Bazac said that “this program was like a gift offered in the dark from a stranger”. Bazac was the new Minister of Health in Boc’s new cabinet and seemed poised to put things in order. “Now, we need to turn the light on and to open the package so that people can see it is a good thing and was given with the best intention”.

Looking back, it seemed like Bazac’s ministry was rolling up its sleeves and started to get things done: they negotiated with the producers to delay the delivery of the second shipment of vaccines so there’d be time to inform the public. He founded the National Information Center for Preventing Cervical Cancer which had a website and a free hotline. He raised the age of vaccination between 10 and 14 years, so that sexuality wouldn’t come as such a distant concept. He launched a two-step informational campaign with specialists to instruct the doctors and the teachers who, in turn, instructed the parents. Bazac took the bull by its horns himself, stating, “I believe in this method for preventing cervical cancer and I’d have no reservations about vaccinating my own daughter”.

An opinion survey carried out in the summer of 2009 with the parents of the new target group showed that over half who were making a decision on the vaccine were in favor of it. Things seemed to be working. In October 2009, the campaign got a second life.

This time, consent was assumed—it was presumed that everyone agreed to vaccinate, and only the parents who did not consent were required to express their choice verbally or in writing (opt-out). And still, there were many who continued to refuse the vaccine. As a result, the Ministry of Health, with vaccines still in their repositories, expanded the age of eligibility to 24 years old, then, in 2010, to 45 years old.

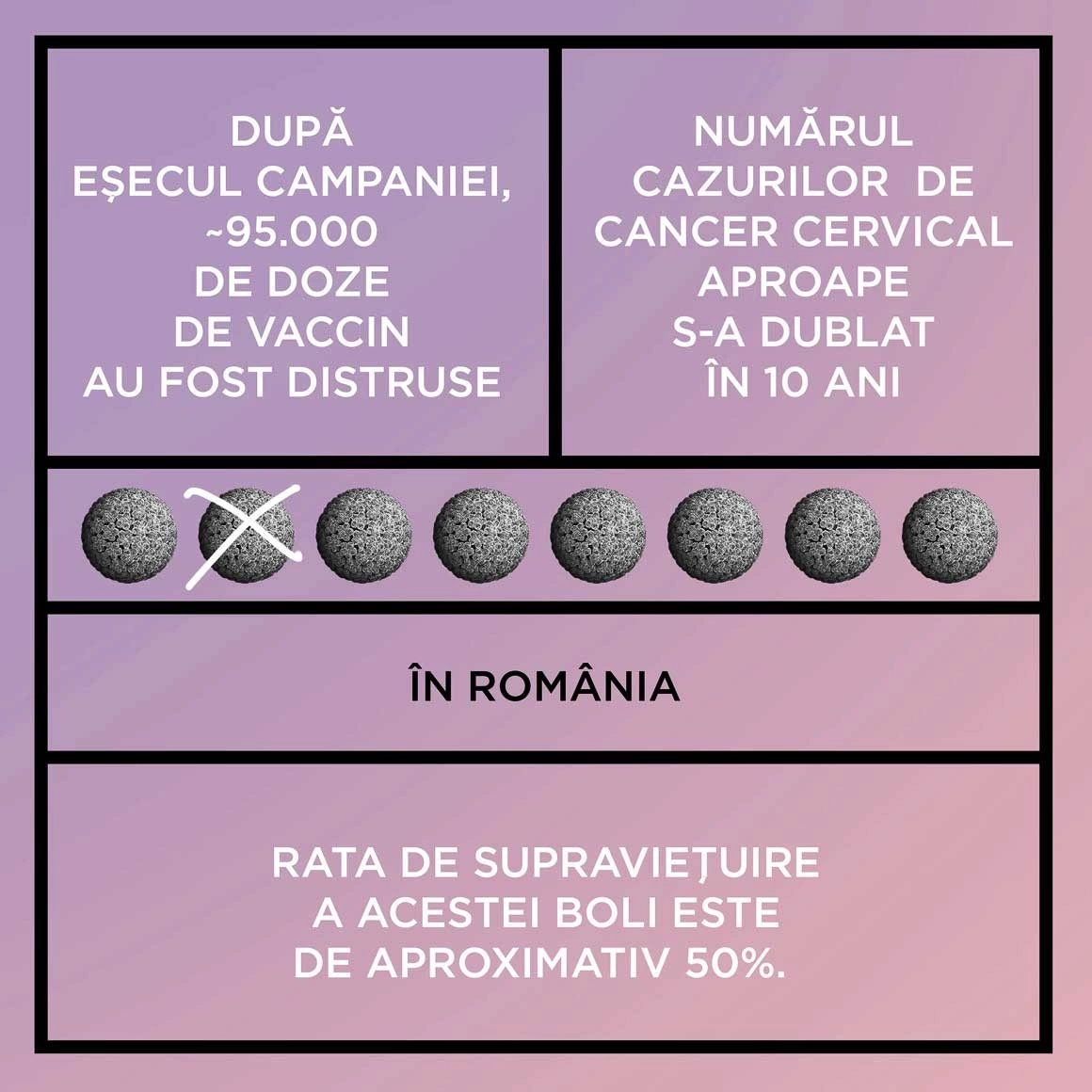

Also in 2010, the ministry returned 50,000 vaccinations still in the validity period to the manufacturers. In 2011, articles in the press began to appear about how batches still in repositories at county health departments were gradually expiring. The Ministry of Health communicated to me that, out of the total 215,489 vaccines they had acquired from manufacturers, only 120,065 were used. The rest of the vaccines, roughly 95,000, were destroyed “through the general procedure of disposal”. The vaccination campaign was officially dead and buried.

Since then, some tens of thousands of women also died of cervical cancer in the last decade in Romania. The number of cases has nearly doubled in 10 years: if, in 2000, 2,862 cases were reported, in 2012, the number had already grown to 4,343 cases. The survival rate of this disease, in our country, is roughly 50%.

*

I was determined not to let my country crowd me into a dark statistical corner. This came to mind—maybe not exactly in these terms—in the reception of the clinic where I was to get the vaccine. The reception door was held open by a fire extinguisher. It was the night before the summer solstice and the heat from outside poured in. In the waiting area, the last appointments of the day were myself and a man fanning himself with a medical brochure, and an old man with black spots on his scalp, like little truffles squashed on his skin, who kept asking his daughter to take him outside to smoke.

I’d found the vaccine at only one pharmacy chain, after asking in over ten: neighborhood pharmacies and pharmacies downtown, pharmacy chains with furniture as bright and colorful as their logo, or plain white and nondescript. The pharmacist packed and rolled up the vaccine in the shape of a doughnut, several times larger than its box, like a grenade. First she took a cooling pack and set it in a white bag, set it in another white bag, and she wrapped them together with a green rubber band, like she was arming a time bomb. At that moment, all the bags of protection were like a sign of caring, their ruffling telling me I was in good hands.. I gave the pharmacist a satisfied look, thinking, finally, someone knows what they’re doing (for me). When I put the white package in my backpack and headed to the clinic, I felt like a kind of fateful courier, like I was delivering a living organ or a state secret.

Now holding my backpack in my lap, in a chair in the clinic, I felt the cold on my thighs and on anything I touched from inside the backpack: the cards in my wallet were cold, my pens were cold in their case, and some ibuprofen pills were cold in their plastic blister packs.

Before she called me to the doctor’s office, the nurse came out into the hall to argue with the receptionist: “We don’t do vaccinations!” “But that’s what they told her at the call center!” “But we don’t!” “But that’s what they told her.” I listened and began to feel all the more clearly that this package with the vaccine carried something impossible and impertinent: transplanted cold into a scalding hot waiting room, a middle finger I’d given to the feverish temperatures and the suffocating statistics of the small world I was living in. The continuous dodging of the people around me had begun to pile up and weighed heavier and heavier on me: I thought I was doing an injection, not an insurrection.

Finally, after phone calls and consultations, the nurse angrily invited me into the office to give me the vaccine. It says in the prospectus that you may get cellulitis at the injection site and I didn’t want cellulitis on my arm, so I decided to get the shot on the side of my thigh. The prospectus said it was ok there too. I stood up, in the middle of the office, holding up the front of my dress, the nurse crouching next to me, a syringe in her hand.

I felt the needle go into the soft layer under the skin and stay there, not entering the muscle, like it was supposed to. The syringe was emptied into me, but my body kept refusing to translate the serum into intensifying pain. When I let my dress down, I was already sure that this wasn’t right.

*

The next day I woke up to a morning storm. The trees violently smacked the window like insolent children. I turned on the lamp and looked where the needle had gone into my thigh. There was a tiny pink dot on the soft side of my thigh, the side I grab like a bag of mozzarella every time I try on jeans that don’t fit. Before going to bed, I drew a circle around the injection with a pen. Two paradoxical and contradictory perspectives were packed into the drawing on my skin: the hope that, by the second day, the mark from the injection would spread outside the circle and, at the same time, the fear that it would completely disappear. The prospectus states that redness, swelling, pain and soreness are common side-effects and I was waiting on them like on a memory of the injection. The main function of the vaccine is to introduce parts of a microbe into the body, creating memory cells which, should they encounter the real infection, even years later, would remember it and kill it. But my body didn’t seem to remember the shot just a day after. My doubt that it would remember years and years later grew.

That morning, I felt like the only friend for me would be an adverse effect. The nurse’s purple scrubs weren’t proof enough of her competence, nor was the family doctor’s stethoscope around her neck, nor the white robes of dozens of pharmacists who’d been clueless about the vaccine. And seeing my gynecologist’s white robes would cost too much money and waiting time (2-3 weeks) to ask a single question about a pink dot. Wherever I turned, I’d be greeted with the same no, I don’t know repeated a capella by a chorus of figures in medical uniforms, then repeated by the white uniform of Google searches which didn’t give any results in the first person when I wrote in my language: am+făcut+vaccinul+HPV (I got the HPV vaccine).

When you find no certainty beyond your own body, you are only left with the guarantees which appear beneath: a bruise, a headache, a sore throat, weakness in the arms. But my skin was still white, my head light, my arms agile, and I wanted an adverse effect as an ally.

*

I feel like I failed to get the vaccine twice. Once now, and another time in 2010, when I was 19 and the state had vaccines in repositories with the initiative to vaccinate women up to 45 years old. It seems like the virus didn’t live in our bodies but in the decibels of our voices, like we ourselves could spontaneously decide when to bring it back to life it and when to bury it, since the people in government—the only voice loud enough to keep it alive—won’t commit to keeping it away.

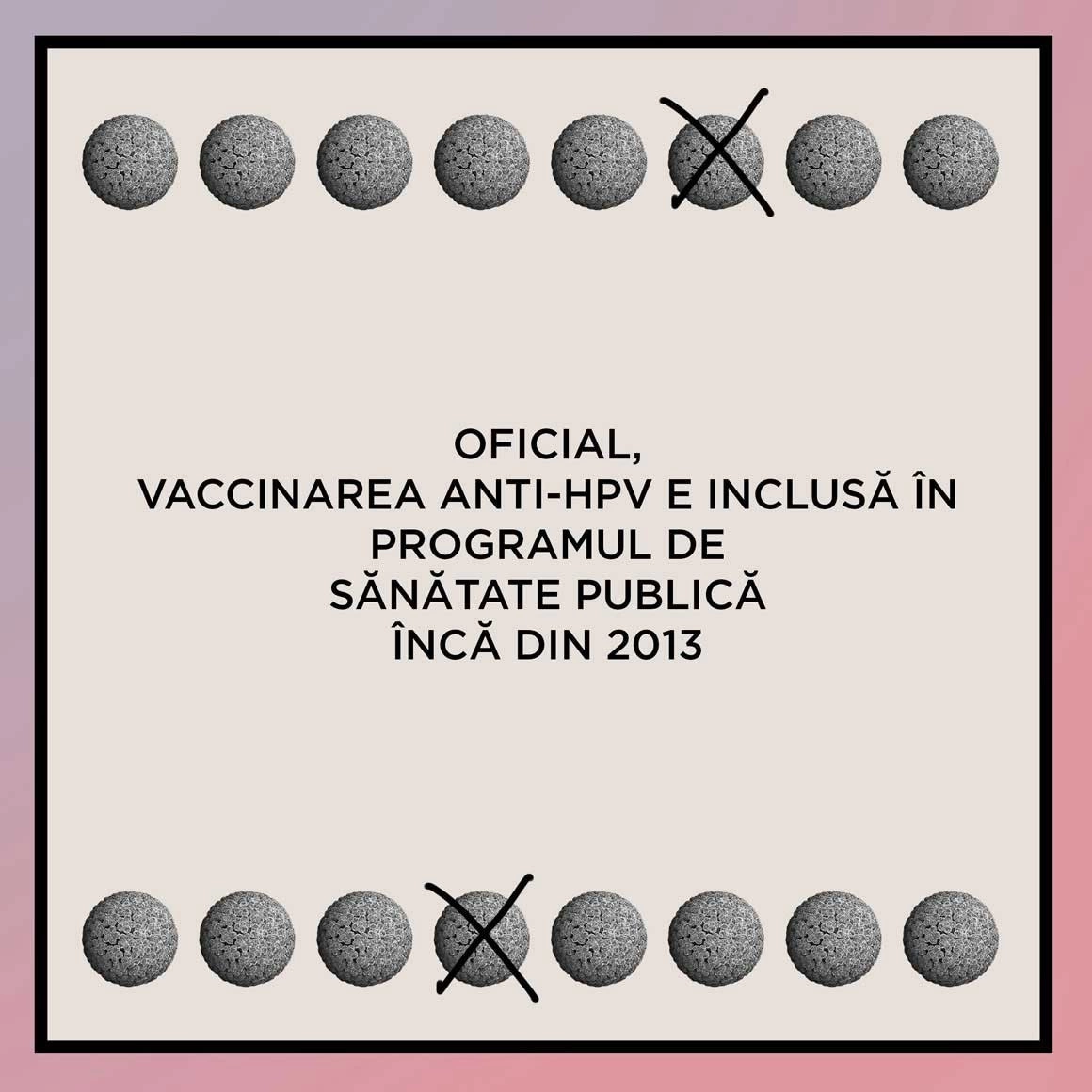

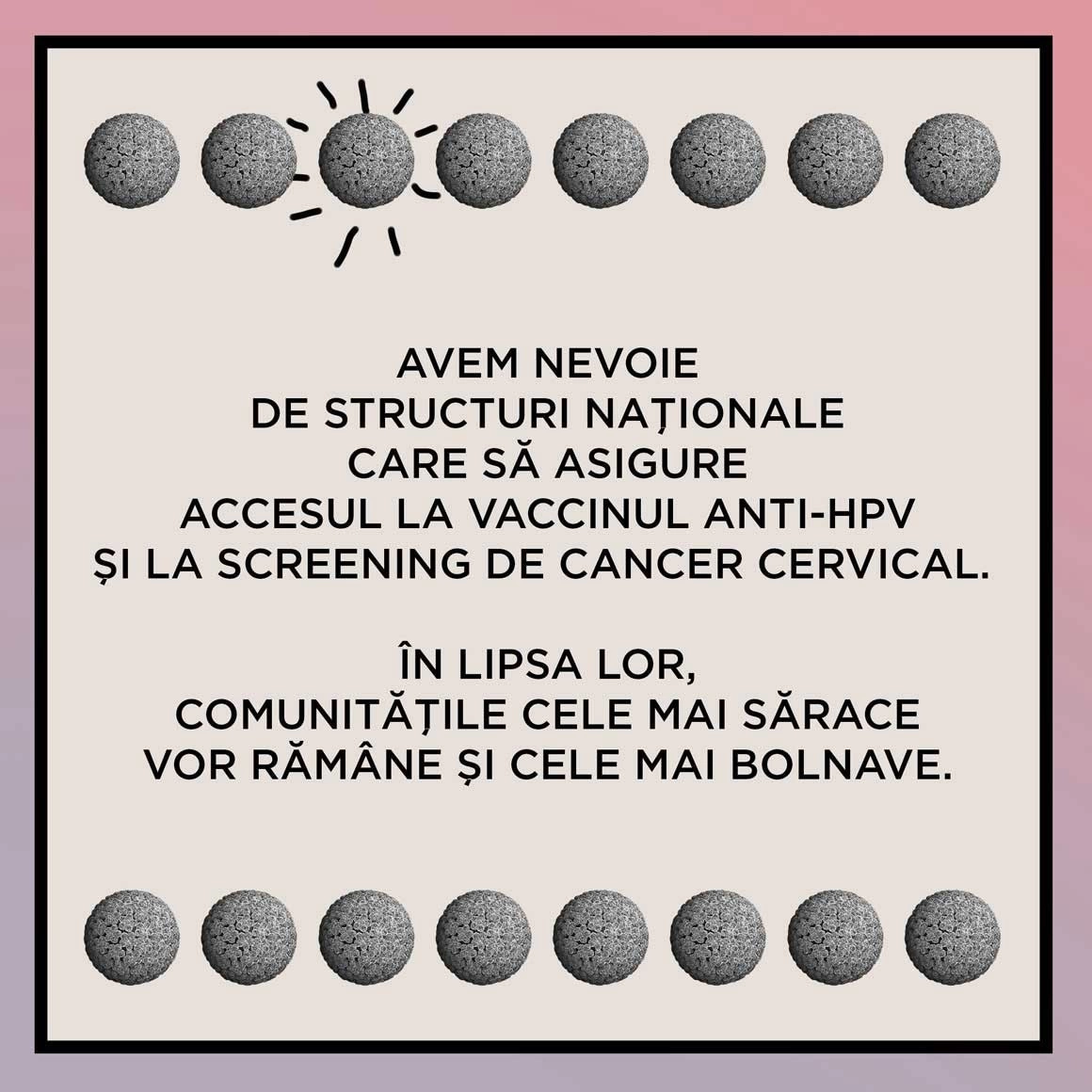

Since the failure of the 2008-2011 campaign, the Ministry of Health has constantly passed decrees mentioning the HPV vaccine as part of the public health program. The decrees come like clockwork, once every two years in the spring (March 2013, March 2015, April 2017). They all lay out the same conditions: the HPV vaccine is guaranteed to the cohort of girls between 11 and 14 years old. Parents who would like it, must submit a request with their family doctor, who will then send it to the county health department (DSP) which, in turn, sends the requests every quarter to the ministry. The decrees in 2013 and 2015 also imposed an informational campaign before the vaccination itself, that was never carried out.

In theory, after receiving the requests from the DSP, the ministry should buy the vaccines requested. It is a strictly theoretical requirement as, for the HPV vaccine provision, there is a slight amendment, in italics: this can be done providing the availability of funds. What’s more, “there is a line for vaccines to be purchased [just like] with car tires,” Doctor Gîndrovel Dumitra explains to me. That’s the way the law works for public procurements: first come, first serve. If there’s a demand for pens and “the pens were submitted in the procurement system before the vaccine, then pens will be purchased first.”

Gîndrovel Dumitra is the immunology group coordinator at the National Society of Family Medicine. He also told me that there are currently 12,000 HPV vaccination requests which have gathered at the national level and have yet to be approved by the minister. Dumitra is a family doctor in Sadova, an area in Dolj county with a significant Roma minority. He became an important figure in the matter of HPV prevention in 2009 when, during the campaign, he vaccinated half of the girls eligible for the vaccine in Sadova. (A local acceptance rate of 50% was huge compared to the 2.57% reported at the national level one year prior.) He managed this after 11 meetings in school with parents and after he “took the lead and told them: I, Doctor Dumitra (…) recommend that you get the vaccine.” Since then, Dumitra has continued to convince patients of the vaccine’s importance and, currently, only a few of the eligible girls’ families have not submitted a request. I ask him how long ago the oldest request was submitted and not yet approved by the ministry. He said that it should be “around 2012-2013”. And some of the people requesting the vaccine will no longer benefit from it as they have aged out of the group identified for vaccination.

If people are having to wait so long for the state to buy the vaccine for them, I wondered how many of them had the drive and, what’s more, the budget to go to a pharmacy and buy it themselves. I asked the manufacturers how much they sold on the private market in the last ten years. GSK responded 10,468 Cervarix vaccines between 2007 and 2015. In 2015 the product was taken off the Romanian market. MSD said that roughly 6,000 Gardasil 4 vaccines were sold between 2014-2017, given that in the previous years there were some “problems in the supply chain,” on which they refused to comment further.

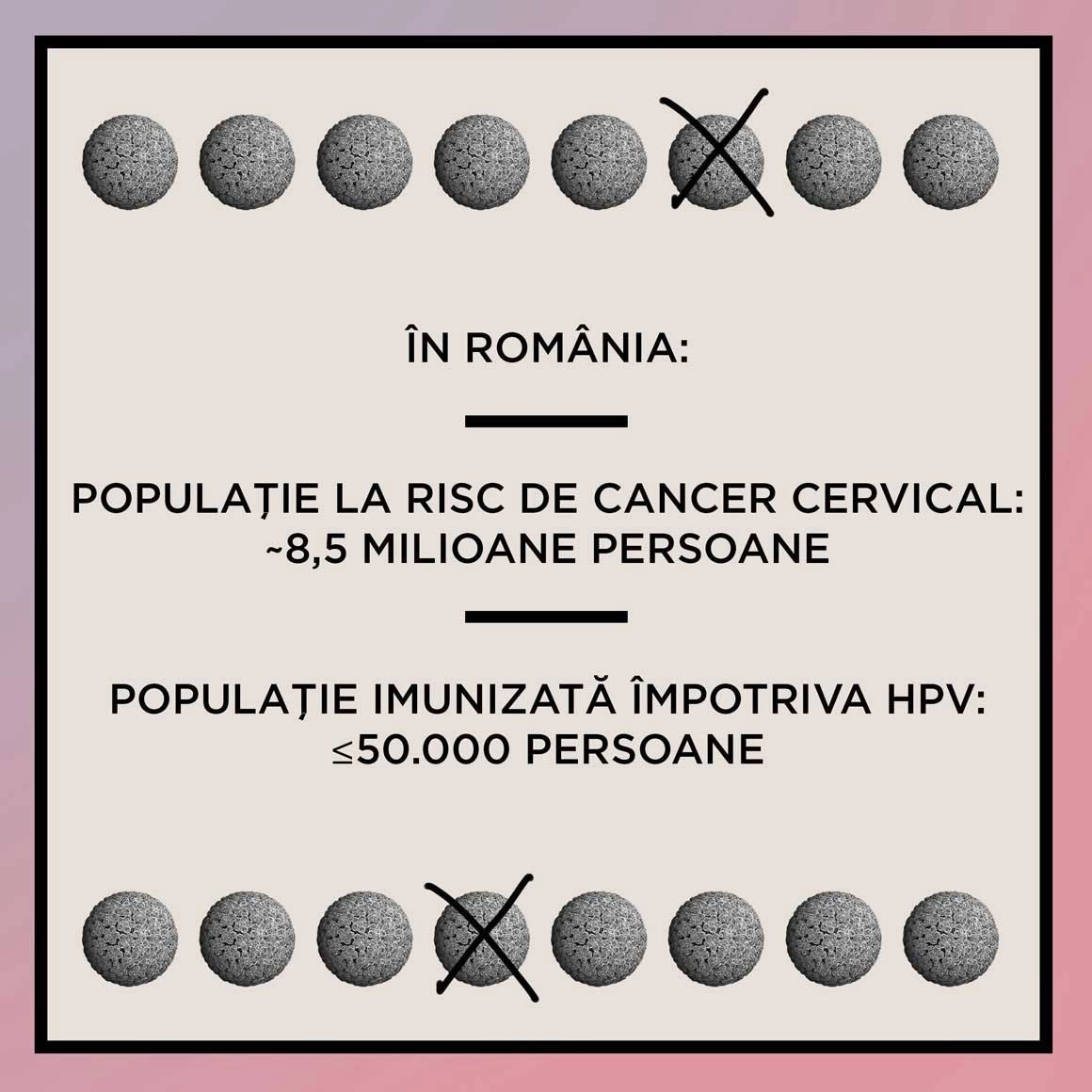

If we add all the figures together and assume that every buyer properly took the immunization—in three doses—then we get about 5,550 Romanians who got vaccinated on their own initiative in the last ten years. If we apply the same logic for the vaccinations purchased during the 2008-2011 national campaign, then we get roughly 43,000 women immunized. Therefore, it would seem that around 50,000 Romanians are completely or partially immunized against HPV. However, a report from the HPV Information Center shows that the population at risk for cervical cancer in Romania is 8.5 million women. So, the current immunization coverage is a drop in the bucket.

About the HPV vaccine, Iuliana Balteș says, “unfortunately, it won’t work that way, only upon request.” Balteș is a family planning doctor. She works at the Urziceni Town Hospital and at the Caraiman Multifunctional Complex, a medical center dedicated to vulnerable people in Bucharest’s District 1. At her office in the Caraiman Complex, Balteș sees people from all around the city and offers them counseling on reproductive health. Then, if need be, she directs them to other doctors who can help them further. About the current situation with requests submitted to the family doctor for the HPV vaccine, she says it’s a painstaking process which didn’t work for her patients: “ this thing only works sporadically, locally and poorly, really.” On the other hand, she says that the 2008-2011 campaign was “well-received.” My eyes grow to the size of saucers. “But first we had to provide counseling for a few months.”

She tells me that the family planning offices were (later) included in the campaign, because not all family doctors can handle talking about a delicate subject like reproductive health, and gynecologists don’t have time. Planning doctors have both: a conversation with Balteș in her office can last between 15 minutes and two hours. “You need to honestly tell people what’s going on with an adequately precise vocabulary,” Balteș says. “And then they’ll understand.” That’s how she managed to vaccinate hundreds of girls at the hospital in Urziceni.

But not everyone was so lucky as to talk with doctors like Balteș, and no illness is more frightening than the unknown. Two researchers in Cluj, Catrinel Crăciun and Adriana Băban, carried out a psychological study with a group of parents following the failure of the campaign. They found that the parents came to believe that the risk of the vaccine’s adverse effects was greater than the risk of cancer. Their study is called Who will take the blame? This was the question in the mouths of the parents they interviewed. It was also a puncture in the bag of collective fear. The state had asked its citizens, for the first time in 2008, to provide informed consent for a medical procedure. They had pushed all the weight of responsibility onto us, but not the information to cushion the fall: the individual needed to be able to answer for his choice, but the state, itself, was unable to answer the people’s questions.

Băban and Crăciun explain how, lacking data, the human brain takes emotion for information, a shortcut called the affect heuristic. The population had filled the logical gaps with fear, had filled the gaps in communication from the experts with conspiracy theories. The rumor was going around that the vaccination was a big pharma experiment in Eastern Europe, a strategy to stunt women’s fertility and shrink the world population. The fact that the vaccine was distributed for free only raised suspicions. “Infertility is seen as much worse than getting cancer”, the authors noted. And at the crossroads of a lack of responsibility on the part of the experts and rampant patriarchy, fear occured. In interviews, mothers discussed that the inability to procreate would have meant, for their daughters, “the destruction of their femininity,” and “no longer being a woman.”

To consider the threat of no longer being able to have kids more serious than the threat of a sexuality transmitted disease means that we separate fertility from sexuality, and it means that we accept an inversion of their order in reality. Cristina A. Pop, an anthropologist who also studied the vaccination campaign, says that the most visible societal norms and taboos are those projected onto the undefined bodies of preteens, such as the 10-, 11-year-old girls included in the HPV immunization program. Pop writes: “[t]heir genderless anatomies do not bear childhood traits anymore, but bode future sexuality and reproductive potential.” Between the two, cultural customs have the say in which will be given voice. In the US and in the UK, it was presumed that vaccination against HPV would make girls’ sexual life begin sooner while, in Romania, it was presumed that it would render them unable to have children. It’s clear to me how their and our speculations on the unknown address the different measures of freedom and duty in social expectations.

Pop studied the failed vaccination campaign in Roșiorii de Vede, Teleorman, in a community at the outskirts of the city and on the margins of medicalization. When it’s a matter of their daughters, the women there talk about “purity” and “virginity”.When it’s a matter of the state-owned health system, they talk about old traumas: the memory of decades of illegal abortions Chernobyl; the fires at Bucur and Giulești maternity hospitals in Bucharest. A woman named Ana proudly tells about how, after she gave birth prematurely, she faked an “attack of hysteria” so that she’d be released as quickly as possible from the hospital. I think about this image: a mother pulling her child back from a state’s watch which has nothing good to offer her. The vaccine, coming from the same deficient state, was seen only as another encroachment on the purity of their daughters.

The meeting of the individual body and the body politic through the act of vaccination is impossible when people believe the two are made of different materials: one of purity, the other of corruption. “Purity discourse” Pop writes, “seems to expand to a form of agency that validates refusal of state-provided medical care.” It makes me think about Ana again. Ana runs away clutching her child.

*

It’s June of 2018 and I’m in a four-star hotel in Sinaia, at the National Congress on HPV. The conference room is dark, the AC is just spewing cold air . I see women’s legs sticking bluish from under their skirts. I think I’m the only woman in jeans and with a backpack. And it’s full: water, sandwiches, sweater, cheese pastry, voice recorder, notebook. Out a window, to the left of the projector screen, the hills arch at their ridges. They’re warm, green, bright. I wonder what the hell I’m doing in this refrigerator full of people in expensive suits. I wonder why we have to talk about a vaccine in a hotel where a night in a single room costs as much as one shot of the vaccine.

The speakers keep showing the same world map in their presentations, where each country has its own nuance on the number of victims, like the disease were another kind of landform. On the projector screen, the map shows all the levels of pain, like a geography of trauma. There are areas where cervical cancer is light pink, a barely perceptible scar line: North America, Northern Europe, Western Europe, Western Asia. Brown spots spread across Africa like great, big blood clots. Russia and Ukraine in orangish coral. Below them, Romania, smaller but more intense, lit red like an ambulance siren stuck in traffic. Over the massive surface of the world, during every speech, I can always find Romania first, screeching and urgent and alone across whole centimeters of map.

The studies show that, due to a lack of structural accessibility to cervical cancer screening programs and to the HPV vaccine, cervical cancer is rampant throughout developing countries and the poorest communities, like that of Ana’s. The disease is so classist that some see it as “a case study in healthcare equality.” Cervical cancer is a biological anomaly but, more than this, it is a social anomaly: it renders the invisible ones visible if it affects enough of them.

In spite of this, it seems like the doctors at the congress find it easier to talk about another category of victims. I hear Victoria Aramă saying that cervical cancer kills “young women, (…) at the height of their professional career.” “Professional women most of all,” adds Radu Vlădăreanu. Aramă and Vlădăreanu talk one after the other at a symposium on Gardasil 9, sponsored by its manufacturer, MSD. Aramă is an infectious disease doctor at Balș, and Vlădăreanu is several things. He’s the section head of gynecology at Elias Hospital. He’s the founder of the Romania Society for HPV. He’s the president of the congress. He’s the doctor who assisted local stars such as Mihaela Rădulescu, Monica Columbeanu, Andreea Antonescu when they gave birth. He’s the man who appears on the last page of MSD’s Gardasil 9 brochures. He’s the man who tells the doctors at the congress to take the brochures (with his face) and to hand them out to their patients. He’s the man whose recommendation makes the loads of materials at MSD’s stand disappear.

During the Q&A after the symposium, Vlădăreanu explains why the government isn’t doing anything for the HPV vaccination: mounting a campaign, even now, would lead to a visible drop in cancer cases throughout the population only after 10-15 years. “That’s why they aren’t financing it, because there are no results during their mandate,” he adds. Everyone claps. I do an interview with him in the hall and ask him if his association pressured the ministry for the HPV vaccination. “The ministry did not seek an opinion from us.” I ask him then if they took any action to inform the population. He tells me that their association is not like an NGO and that they have other work to do. “I have neither the time nor the patience nor the necessary internet to sit around and ask….” The sentence was left suspended, without an end. Vlădăreanu fumbles madly with the keyboard on his phone and avoids eye contact with me.

In fact, few people find the time and patience and internet to ask the ministry. At least that’s how it seems when you search on Google. In February 2013, the National Patient Protection Association made a call to the ministry to relaunch the HPV vaccination campaign. In 2017, the deputies Costel Alexe (National Liberal Party) and Petru Movilă (People’s Movement Party) each submitted an inquiry to the Ministry of Health asking what they plan on doing for the whole cervical cancer situation. In February 2018, the deputies Cosette Chichirău (Save Romania Union) and Antoneta Ioniță (National Liberal Party) each submitted an inquiry. Both asked for roughly the same information: how many parents’ requests had the Ministry of Health received, how much money will they allocate to purchase vaccines and roughly when will it do so.

The ministry gave the four deputies pretty much the same answer in the same ambiguous voice linking the tenses of an unfulfilled promise to a future full of possibilities. “The vaccination has not been carried out over the last years,” funds “were insufficient,” “it’s not in the budget.” BUT, the ministry “is looking at” drawing down Norwegian funding and “steps will be made to amend the budget.” In none of their answers can you find any responsibility or explanation for the grim facts they’re listing. What you do find, invariably, is assurances of their “highest consideration.”

On the Chamber of Deputies’ website, I downloaded all four testimonies of indifference. I saved them in a folder called HPV_politic. I gave each one a number according to the order in which it appeared, along with the name of the deputy to whom it was addressed. Evening after evening, I opened them in Adobe Reader, each time in an orderly row of tabs which I blankly stared at, not knowing what to do with them. I went from one to the other with a wan click, left to right, right to left, as if the meticulosity of this inventory could compensate for its futility. Then, I closed them all and went to sleep, without so much as a new shred of understanding.

“The vaccination has not been carried out over the last years.” This sentence, making clear that the state had been doing nothing to prevent its citizens from dying of cancer, to me seemed to hamstring any means of fighting against an irresponsible government. Cosette Chichirău confirmed this for me. “They are the executive, they execute. And if they don’t execute, there’s little you can do to them.” I interview her about the inquiry she submitted at the Ministry of Health. We talk on the phone because she’s in Iași and I’m in Bucharest. As we talk, I feel like I’m getting further still from a solution. All punctuation marks fall away from my sentences like an unravelling necklace—hopelessness often renders me incoherent.

Some weeks after the discussion with Chichirău, in July of 2018, Health officials confirmed in an email that “since the year 2008, the Ministry of Health has not procured any kind of HPV vaccine,” although “approximately 6,000 requests have been submitted per quarter every year.” This would mean an average of 24,000 requests submitted annually—double the figure Dumitra told me, which was also circulating in the press. Yet the ministry does not mention for how many years it’s been keeping track, making it so I could not determine how many people were being kept on hold, waiting for the Government to acknowledge them.

Chichirău says that the only instrument available to the opposition in Parliament to impose that the government, the ruling party, take action would be through a law. However, in the case of the HPV vaccine, this is not a viable tool: vaccination cannot be legislated because it is already included in the national immunization program. She sums it up for me, “that’s the problem. The government is assuming obligations which it doesn’t meet.”

In the same email from July of 2018, Ministry of Health representatives wrote that their institution requested that the budget be amended that summer for funds covering 12,000 vaccines, fulfilling 6,000 requests. (If, in 2008, the experts considered that three vaccines are needed for ideal protection, they have since decided that immunization with two vaccines is just as efficient if it’s done before the age of 15.)

I wrote to the ministry again, in the fall of the same year, to ask how much money they requested for the 12,000 vaccines and if the funds were approved. “The estimated necessary funds for acquiring 12,000 HPV vaccines comes to approximately 7,034,554 RON. The Ministry of Health will begin the acquisition process for this vaccine in the near future.”

I wondered if the “estimated necessary funds” for a vaccine meant “allocated funds.” I wondered what “the near future” meant. If the authorities know how much it costs does that mean they are also going to pay it? And if so, when?

I asked for clarifications and they clarified. “The Ministry of Health intends to purchase the HPV vaccine (…) in the year 2019.” They also said that the minimum required would actually be 50,000 vaccines—4 times more than stated in the prior email --, and that “it intends to undertake the steps” towards the signing of an acquisition framework contract for the relaunch of the national campaign. But all this next year, a fantasy world containing the classic proportionality of a populist government: if the problem grows in scale, the horizon for a timely resolution is pushed back.

In the meantime, seven NGOs sent a letter to the Government requesting—on the occasion of the same budget amendment in the summer of 2018—that they adhere to the provisions of the National Vaccination Program and they allocate the funds for the vaccine. I was happy to hear the news about the mobilization of civil society, and then I read the letter from one of the signatory NGOs. The petition had recycled the same rhetorical chronology from the deputies’ inquiries. The mortality rates of women between 15 and 44 years old. The appearance of the vaccine in the National Vaccination Program in the category “demographics at risk.” We are EU leaders “regarding both the cases and mortality rate of cervical cancer,” and the letter contained the same grammatical errors as one of the deputies’ inquiries.

Clearly the synchronization of the political arguments and those of the civil society is not a coincidental consensus but came out of the same head. Andreea Bragă, director of the FILIA Center which was a signatory organization, confirmed as much. “[The idea of the letter] was suggested to us, and our association somehow endorsed it.” In fact, the petition’s strategy was orchestrated by Good Affairs, a lobby and market access company which then worked with MSD to push the vaccine onto policy makers. Sânziana Mardale from Good Affairs is the one who, according to Bragă, “coordinates this activity of gathering signatures, of mediating with NGOs.” Mardale and her team also advised Deputy Cosette Chichirău in the first inquiry submitted to the Ministry of Health and informed her as to what budget to request in the second letter, during the budget amendment in the summer of 2018. “I will request 25,000 vaccines,” she stated, “at 600-something lei per vaccine,” which was the price—as was whispered to Streinu-Cercel at the conference—it sells for in the pharmacies.

During our first discussion over the phone in June of 2018, Chichirău told me that Sânziana Mardale’s team “does a pretty good job of keeping me updated or asking me to do one thing or another.” During a conversation in September of the same year, I asked her if she doesn’t see any conflict of interest in the lobbying agency representing the manufacturer and proposing she undertake certain activities, telling her how much to ask the Ministry of Health for the vaccine. Chichirău answered that she already had “a very clear interest in the subject before,” and the meetings with Good Affairs only helped her to get more information much easier. The team’s lobby efforts only had the effect “of reminding,” like she was being told, “hey, you care about this subject, right?”

“That’s right, I care about it,” Chichirău says over the phone during a fall evening.

Between our two discussions, in June and September of 2018, Chichirău did not submit the second letter to the Ministry of Health which she’d been planning on sending that summer, during the budget amendment. Sânziana Mardale and Eliza Rogalski from Good Affairs confirmed that their agency had arranged meetings with Chichirău and the other three deputies—Movilă, Alexe and Ioniță—who also made a Government inquiry on HPV vaccination. The letter initiated by Good Affairs and signed by the seven NGOs never got an answer from the authorities. And my letter, wherein I asked them if they actually allocated money for the vaccine in the summer budget amendment, was only met with a delay to the solution.

I also asked Chichirău if the money was allocated for the vaccine after the amendment and she told me that she didn’t know. I asked her to help me and to check, and I wrote a WhatsApp message a few days later to ask her again and, because it was a few days before the anti-gay marriage referendum and she was the president of the party’s committee in her county, monitoring over 700 polling sites, and was “under water,” she didn’t answer. I was tired of unanswered messages and I couldn’t stop thinking about how, in a country impaired on so many levels, the only apparatus which keeps attention on a life-saving vaccine—albeit expensive and taboo—is the industry of reminders also known as the lobbying industry, for a healthcare industry which is also known as big pharma, and how somewhere in the middle, between the silence financed by public funds and the commotion reimbursed from the safes of a pharmaceutical goliath, our whispered fears struggle to survive in the distance between us.

*

Walt Whitman writes: “I too had receiv’d identity by my body.” And continues, “That I was, I knew was of my body—and what I should be, I knew / I should be of my body.”

When I decided to get a vaccine that a whole country doesn’t get, I was—like Whitman—convinced that that I am, I am of my body. I was the first to my family doctor, first to the pharmacies, first to the call centers and first to the nurse in purple scrubs, and every time I would make note of this position, first, I would secretly fawn over myself, like it was a trophy I’d won, like the encumbrance wasn’t shared among us. It took an imprecise injection for my initial idea to be made more precise: the condition of my body is essential but insufficient for my existence. What I should be, I now know I should be of the body of the other.

I wish I could tell Whitman that, even though I suspect he wouldn’t have been totally unfamiliar with the idea. But I still wish I could tell him, loud and clear, the way I wish the guy from Tinder would have told me, denying me any access to indifference.

It was two months after my first vaccination —due already was the second one—, that I’d just begun to think about giving up my search for the guilty party and accepting that the world around me simply cannot keep me any healthier than it can keep itself. In my failed vaccination attempt I could read the millions of people before me who did not get vaccinated.

In medical work, as in the sexual act, my body is, to the other, the object of a long line of knowledge derived from the bodies of other women. We do not belong only to ourselves, and our health is not a merit granted only to our names—at best, it is our private holding and we give every piece of the world with which we intersect usufruct rights to it. This is all coming into the picture for me and I hope it is for the government officials, as well, because our last chance to act is now.

A note on biases and limitations:

This piece began from a Google search of “I got the HPV vaccine” in Romanian. The search gave no results written in the first person, so I decided to write about my own experience of the vaccination against HPV. At first, I imagined the text to be an investigation into the vaccine’s clinical and emotional implications in my life. It followed that, at the beginning of June, I wrote an email to Cristina Velicu, Public Health Manager at MSD, proposing a naïve and questionable trade with the drug manufacturer: to offer me the vaccine for free in exchange for me writing a text which would serve to raise awareness about the dangers of HPV and about the benefits of the vaccine. Fortunately, my editor, Luiza Vasiliu, turned down this undertaking and the cost of the vaccine was included in research costs covered by the editorial staff. The idea of collaborating with MSD was not pursued so as to retain the independence and objectivity of the research. I thank Luiza for wisely raising the red flags and for setting me on the ethically sound path.

As concerns the doctors quoted here, the lists (2014-2017) of sponsorships published by the National Agency for Medicines reveal that three of them have benefited in the past from smaller or larger payments from MSD. They are Gîndrovel Dumitra, Radu Vlădăreanu and Victoria Aramă. (The latter of the three neglecting to declare income from her collaboration with MSD and, thus, the amounts can only be found on the lists provided by the manufacturer.) I met with, listened to, and interviewed all three experts at the National HPV Congress in Sinaia in the summer of 2018. Payments made to Doctor Adrian Streinu-Cercel by MSD—mentioned here in the context of the Gardasil 9 launch—were published by a RISE Project investigation.

Rogalski Damaschin PR is a public relations agency that was contracted, at the time of this reporting, to represent MSD’s interests in Romania. Good Affairs is a lobby agency which collaborated with Rogalski Damaschin PR to represent their shared client, MSD. Lobbying activities, themselves, are not problematic, however, in the absence of transparency, they are. Good Affairs interfaced through Sânziana Mardale, an employee at the agency, with four of the people I interviewed in this piece. They were also invited to get involved in promoting the vaccination. I spoke with Deputy Cosette Chichirău and the representatives of three of the NGOs who signed the letter introduced by Good Affairs: Andreea Bragă (FILIA Center), Maria Isabella Pîslă (FASFR) and Carmen Suraianu (SECS).

In the interviews with the representatives of the NGOs it came out that Mardale never informed them of the business relationship between her employer and the vaccine’s manufacturer, or of the consequent potential conflict of interest. Two of the presidents of the NGOs told me that their interaction with Sânziana Mardale was based on her position as the promoter of the national informational campaign “Protect Their Wings”. The campaign was carried out by MSD in collaboration with the Institute of Public Health and coordinated and implemented by Rogalski Damaschin PR. Good Affairs used the campaign materials as means of information and persuasion both for the three NGOs, mentioned above, and for Deputy Cosette Chichirău.

The three representatives of the NGOs declared that the letter for the Government was sent to them by Sânziana Mardale of Good Affairs who'd written the letter. I could not find the letter published anywhere, however one of the interviewees sent me a copy of the letter signed by their organization. This was a Word document titled “Letter_civil society_HPV vaccine budget allocation_23 July”, and “Merck & Co., Inc.” is provided as the document’s author.

Concerning political involvement in the anti-HPV vaccination issue, Deputy Cosette Chichirău’s inquiry came to the Ministry of Health on the same day as that of Deputy Antoneta Ioniță, February 13, 2018. I wanted to understand what was behind this concomitance and tried to contact Ioniță by email, but she never replied to my message. Chichirău said of the coincidence, “if it’s in February, it’s probably due to the beginning of parliamentary sessions.”

I also contacted the other two deputies who submitted an inquiry related to the vaccine a year earlier, Costel Alexe (National Liberal Party) and Petru Movilă (People’s Movement Party), to learn what prompted their initiative. Neither responded to my email at the time of this text’s publication. On the other hand, Eliza Rogalski, head of the strategic department at Good Affairs and of the corporate communication department at Rogalski Damaschin PR, while also being a shareholder with both companies, confirmed to me that her team had meetings with all four deputies who submitted inquiries to the Ministry of Health.

Talking with the four women involved in the activities initiated by Good Affairs, I felt that they were not previously aware of Mardale’s association with MSD and that they’d begun to see the connection more clearly only during our discussion. Regarding Sânziana Mardale’s practice of not informing the NGO representatives of the relationships between her employer and the manufacturer of the vaccine, Rogalski refused to provide written comment.

Editor: Luiza Vasiliu

With help from Sorina Vasile and Victor Ilie

Additional note: some days after this piece was published, the Rogalski Damaschin PR agency sent a right of reply on behalf of the manufacturer MSD Romania. You can read it in Romanian here.

Translated by Andrew Davidson-Novosivschei.