The life of Tania Mouraud is a work of art. At 74, Tania employed all the means of projecting on the outside how the world looks like on the inside of her own consciousness. She started painting in the ‘60 but shortly she burned all her works and has not stopped experimenting ever since. She converted words into objects, she tried photography until she melted images into paintings, she transformed sound into something concrete, and she used the camera to ‘take notes’ from life in order to induce the spectator into trance.

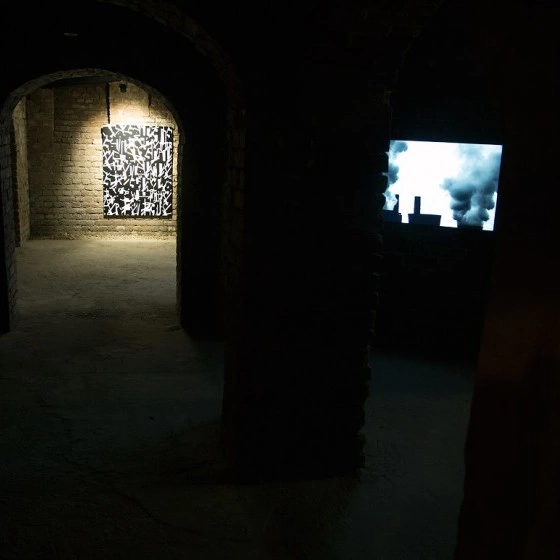

On 19 may, at 19h, at Eastwards Prospectus Gallery in Bucharest, Tania Mouraud’s OTNOT exhibition opened, comprising on two floors some of the newest works belonging to the French artist. The ground floor gives the impression of a conventional exhibition, incorporating only photographies. Some of them, displayed for the first time, belonging to the Balafres (Open wounds)

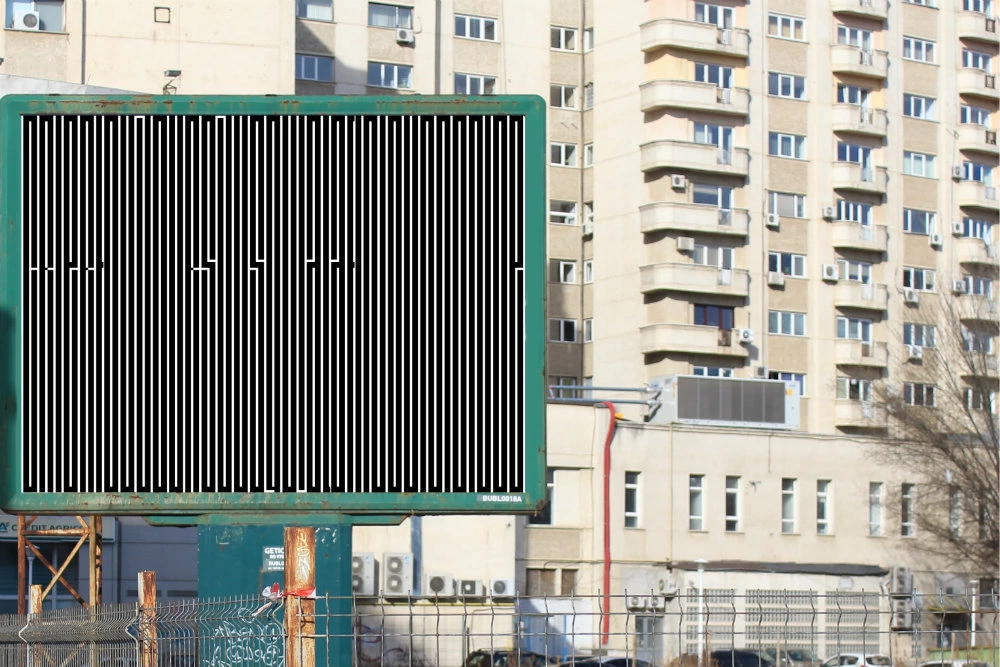

series, depict the beauty of a disaster: a lignite quarry in Germany which, seen from a great distance through the lens, looks like the landforms of an alien planet. But the video installations and the digital ‘writings’ at the basement transport you directly in the depths of the world, as Mouraud says. Pandemonium, a video artwork divided into three screens, showed for the first time too, looks like a moving and sound-making painting that depicts furnaces continuously spitting out dark clouds. I remained minutes in a row in front of the enormous screen on which the work Face to Face is played in a loop, hypnotized by a gigantic iron arm which, like a deadly flower, swallows the garbage from the biggest garbage dump in Europe. No Name is the heart of the exhibition because one can trace its sources deep into the personal history of the artist: a part of the work is recorded in the Jewish cemetery from Iasi, a place Mouraud visited recently searching for her roots. Her Jewish father was born in Roman whence he fled for France. OTNOT, a name you must decipher by yourself in the gallery has an extension on the streets of Bucharest and various Romanian cities in the form of billboards; these are the medium on which Mouraud chose to write one of Benjamin Fondane’s verse. I recommend you to try to decipher it when you will discover them among the city’s numerous ads.

A couple of days before the exhibition I talked to Tania Mouraud, an experience that made me hope time would dilate.

I saw your video works displayed in the basement of the gallery and I felt overwhelmed.

This is exactly the purpose of the exhibition: to share. All I want is to share my emotions with the viewer. After all, we all want to have a close friend with which to share all the significant things in our lives. The advantages of an artist in a free state is that he can express what he thinks and he can say this is what I see.

An act of generosity.

I cannot label it, but you can. All I can say is that us, human beings, are very alone thus being an artist is a way of dissolving the solitude of existence. It is a way of making your voice heard and of telling things that one hundred years ago were prohibited. You, whose parents lived through such a horrifying history, know it all too well. I was lucky my father fled Romania for France, where he was reborn, thus I haven’t known the impossibility of sharing.

In this exhibition as well as in all your work you always alternate between interior and exterior approaches connected to an interior universe or to an exterior, societal one. How do you find the balance between these two worlds?

People form my generation were born during the Second World War. Actually, we were born into death. We were born in a cemetery – Europe only had approximately 38 million dead. My father, as well as my entire family died with the exception of my mom. Thus I was born when history was being made. Many of today’s artists make such a Disneyland art precisely because this is the history we live in. When I was born there was no Disneyland, only suffering which was everywhere you turned your eyes to. I think I managed to balance the prospect of death and continuous suffering by employing aesthetic values in my work.

You don’t judge through your work, even though you present the viewer the image of a disaster.

That’s exactly it, I never judge and this is why the viewer is free. I really like to work with destruction. In my childhood war was everywhere and Hiroshima happened everywhere, then I grew up during the Cold War. I could only perceive around me the anxiety that the government liked to instill into the people. If we think a bit about it, even the stories that our parents tell us throughout our childhoods are dark, but we love them. Even though I am fascinated by all kinds of destruction, I never judge and my works are never political. Not one of these photographs can be used for political or ecological causes. If someone were to use the photo from the lignite quarry for criticizing Germany, the rest would say gosh, what a beautiful image. (Laughs)

You started your career with a destructive act aimed towards yourself. You burned your work.

Everybody is fascinated with this auto da fe. But honestly speaking, it was only my character. I was so tired of that art – because what I was doing was a case of bad painting – so I told myself this is not art, give up, let’s burn everything! (Laughs)

Following the evolution of your work I noticed that at the beginning you focused on your place in the world and as time passed by your view enlarged and started encompassing social and historical issues. Is this how your way to maturity looked like?

Certainly. When you are young, everything you see is peace&love. During my artistic infancy, I tried to create things that would convey peace&love. Then, the situation changed and I started reading more. For example, in Germany I read Bertold Brecht and I was deeply influenced by what he was saying about the responsibility of the artist. During that time, you were suffering here because of the communist regime, but for the French being communist was a sign of freedom.

How do you think the role of the artist changed from the ‘60 up until now?

You will be amazed by my answer. I will translate your question about the role of the artist into one concerning the role of the mother. Not the mother that cleans and cooks, but the one who transfers values to her children, who prepares them for facing life. My father died for liberty and I will transfer to my kids the same ideals he had. I am telling and teaching them not to become slaves, to be brave and strong. To be happy. The same thing I could tell all the artists. Don’t follow a trend just for the money, chose an ideal and respect the others.

You say that artist shouldn’t care about the money, but being an artist becomes more and more professionalized.

Certainly, for some that are boring and don’t care about you, art becomes a job. But you cannot quit art, as you can quit a job. When I taught art classes I was very happy and free to do whatever I wanted, without having in mind that I should sell my works. I never create for selling. I create because I think it is important to do it.

How is it to have such profoundly personal works in private collections?

If you are in a good collection you are happy because, implicitly, you are in the company of good artists; moreover, a person who has a good collection is a good person and if she/he bought your work then it means that you share a vision. Other times, my works ended up in collections that I didn’t like and I felt extremely sad for not having the money to buy them back.

But how do you feel when you see your art in a museum?

When I was young I was very unsure – I still am. When I first saw my works in a museum I felt even more skeptical. And as I like to forget the past, I found it extremely difficult to organize the retrospective from 2015 at Pompidou. It was terrible, because I am the kind of artist who only likes what she does in the present. Although I discovered works that I haven’t seen in 50 years and I told myself wow, this is extremely good!

Many artists specialize in only one medium, they are either painters or sculptors. You continuously changed the mediums in which you work.

That’s right, because I really like playing. It is as if you would have a new game, whose rules you don’t know or if you think it’s rules are way too complicated you invent new ones. Not because you are some sort of a genius, but because you want to play. It is like when a kid who wants to win a game which is unknown to him, we adults say he is cheating. Cheating means inventing new rules. (Laughs)

Are there ideas that you couldn’t translate in an artistic form?

There are many, many, many of them (Laughs) For example, every year, starting 1971 I go to India. I think I waited for forty years before making a work in India. But when La Fabrique was ready I felt Vrrrrrrraghhh! It is one of my best works: a video installation, with material recorded in a factory in India. It is the only work in which there are people, even though it is not about the people, but about the machines. In the recordings, you can see the bodies of the workers almost dislocated by the machines they work with on a daily basis and this image of destruction is terrible.

In many of your works the machine reigns: gigantic excavators which rummage the ground, the machine who destroys books, the machine controlled by people in a factory, the machine which growls deafeningly and spits dark clouds. Where does this fascination for the machine come from?

Maybe – but just maybe – from Antonioni’s Red Desert. But, after all, why do I like this movie? I don’t know why I am so fascinated by machines, but I know two things concerning this issue. In every place I go to create only men work. And, for me, the human being is not bad, but the system is, and I use machines as a metaphor for the system.

We now live surrounded by machines more than ever. How do manage this situation?

Very, very well. (Laughs). I am a geek. And I have 4.800 Facebook friends.

How and when did you start searching for your Romanian roots?

Honestly speaking, until recently I wasn’t interested at all by my Romanian origins. Because I was a free French republican woman. And that’s that. Then, in 2007, I went to the Sublime Objects exhibition at MNAC. My work, as big as an entire wall, contained the message I haven't seen a butterfly here because the museum is located in the palace of a tyrant and because it was the title of a poem written by Paul Friedman (an artist who survived in the Theresienstadt concentration camp and then killed in Auschwitz). At that time, Romania did not recognize the Holocaust and that was my way of taking revenge. This first visit was extremely difficult after so much time during which I blocked all this part of my life. Later, I went to Iasi where I recorded the work now displayed in the basement and this is when I started to find out more about what happened with the Jewish community in Romania. Since then, I learned to play Klezmer music at the clarinet, a thing which helped me accept my origins which I was denying. And I discovered Benjamin Fondane, who has a story similar to my father’s and who wrote this verse: Crier toujours jusqu'à la fin du monde (Scream until the end of the world). In a way, this is also my message – whatever happens in this world, it cannot silence me. I will scream until the end of the world.