Over the past months, US and European cities have seen numerous statues knocked off their pedestals, covered in graffiti, sprayed with blood-red paint and, in some cases, removed by the authorities, scared of the protesters’ rage. The targets are invariably men who held power capital, at various times in history, which they employed both for political and economic reasons, as well as for fostering slavery and racism. What place do these statues hold in the collective memory and why are they being contested right now?

For a few months now, the entire world has seemed united - or at least shaken - by the same concerns. Until recently, the monopolizing theme on news channels in China, Europe, the US, South America, Africa, and Australia was the new coronavirus. After George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis, the debate on countering the pandemic was accompanied at an almost global level by protests against racism. Initially organized in solidarity with black people in the US, they soon became denunciations of local racism in the United Kingdom or Germany.

Of late, the public agenda has also accommodated the topic of statues associated with slavery or colonialism and their toppling by protesters in the United States, UK, and Belgium, all the way to New Zealand, as well as similar statues and monuments being contested in numerous other countries. Among others, the statue of slave merchant Robert Milligan was removed in London; the statue of Jefferson Davis, former Confederate president and plantation and slave owner, was sprayed with paint and then torn down by protesters in Richmond, Virginia; a London statue of Winston Churchill, who supported the idea that whites are superior to other races, was placed under watch after being targeted by protesters; and a statue of King Leopold II was removed from the public space by Antwerpen authorities. In fact, King Leopold II, whose reign saw the abuse and massacre of Congolese populations in the Belgian colonies, was also ‘attacked’ in Brussels; his statue was immediately covered in graffiti again, after being cleaned by the authorities.

In all these cases, from the coronavirus, to the antiracist demonstrations and to the sometimes spectacular toppling of the incriminated statues, we seem to be dealing with a domino effect or a bush fire spreading from one corner of the world to the other. But beyond the dizzying speed of contamination - either with the virus or protest gusto - is there a common denominator to these events?

The large number of racist aggressions targeting Asians all over the world, since, early on during the pandemic, they were regarded as ‘default’ virus carriers, says there is one. The aftermath of these often violent attacks saw the emergence of such anti-racist slogans as “I am not a virus” and “Racism is the pandemic”. The studies according to which people of color in the United States, Europe, or South Africa, as well as indigenous populations in Brazil or Australia are more exposed to the coronavirus and disproportionately contracting COVID-19 also point to a strong link between a virus, which, in theory, cannot discern between people’s origins and nationalities, and the profoundly unequal system within which this virus is spreading, thus, in practice, exacerbating preexistent inequalities. But what do the statues have to do with this discussion?

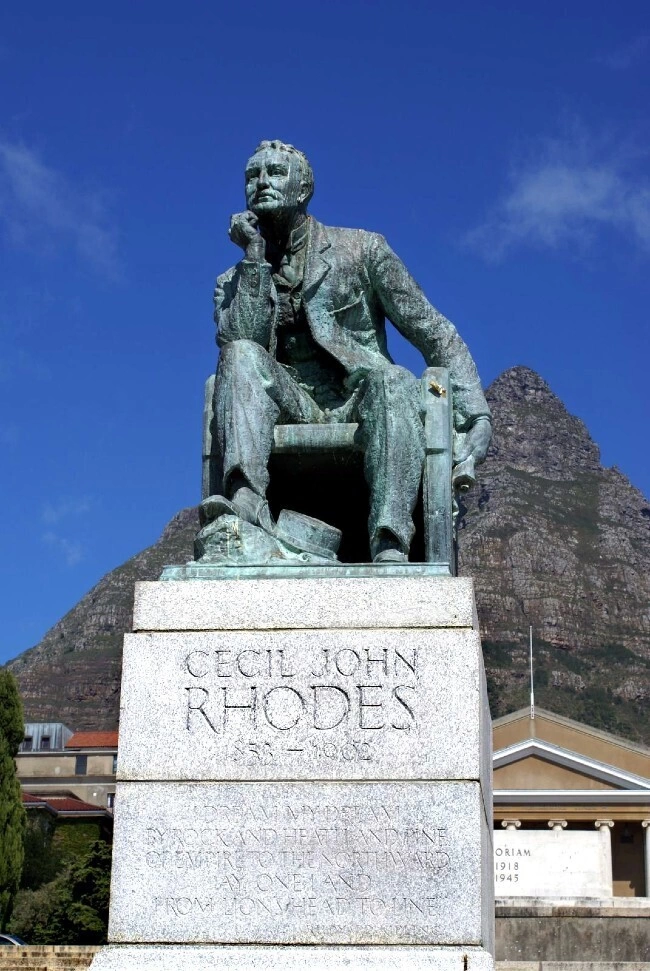

Critics often view the practice of tearing down statues as a mere makeover or even a purge of collective memory, which does nothing to change the unequal structures or racist attitudes in today’s society. The motivations of the protesters who toppled and flung the Bristol statue of Edward Colston into the water, a slave merchant with the Royal African Company, or those who paint-bombed King Leopold’s statue in Antwerpen, or those who are debating the need to remove the statue of colonialist tycoon Cecil Rhodes off the premises of Oxford University, or the Bismarck towers in Cologne and Berlin, are seen by many as politically correct exaggerations, if not as senseless vandalism, even.

Conversely, supporters of the protest movement draw attention to the fact that collective memory isn’t only preserved through monuments, but, first and foremost, through reading and civic education, while the removal of statues and the debates that preceded it are by no means new under the sun. They are, however, more visible: on the one hand, because of the chain of events that brought racism to the foreground - from the pandemic to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Rayshard Brooks; on the other hand, because they are being debated in parts of the world - the United States and Europe - which, for a long time, held racism for a problem foreign to - and even independent of them, that supposedly only existed in the former colonies.

Harriet Tubman graces the Lee monument this evening, beneath a quote: “Slavery is the next thing to hell,” and “BLM.” pic.twitter.com/lW5CUf7bIJ

— Zach Joachim (@ZachJoachim) June 21, 2020

In the above tweet, the image of abolitionist activist Harriet Tubman is projected onto the statue of Robert Lee, Confederate State Army commander during the American Civil War. His statue is located in Richmond, Virginia.

Indeed, Cecil Rhodes' statue was removed from the campus of the South African University of Cape Town as early as April 2015, following students’ protests to decolonize education - an aim deemed incompatible with the statue that paid homage to tycoon and politician Cecil Rhodes. However, there had been repeated calls for its removal up until that point - for the first time, in the 1950s, by Afrikaner students, descendants of the largely Dutch colonists in South Africa. Rhodes (1853-1902), prime minister of the Cape Colony during the British occupation and founder of the De Beers mining and diamond extraction company, founded a state initially called Rhodesia, which became Zambia and Zimbabwe respectively, after attaining independence. He was also an ardent supporter of the British Empire and of the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon ‘race’ at a global level. The protest movement initiated at the University of Cape Town, under the name “Rhodes Must Fall”, shortly thereafter followed by “Fees Must Fall”, which targeted the increase of university tuition fees, soon exploded at national, and then global level. The attempts to remove Rhodes’ statue from the frontispiece of the Oxford college that had served as alma mater to many heads of state (such as Bill Clinton), renowned politicians (such as Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull), and successful authors (such as Naomi Klein), through the support of the prestigious Rhodes international scholarship, were met with failure in 2016. At the time, Lord Patten, chancellor of Oxford University, refused to take any measures and claimed that “Education is not indoctrination” and that “Our history is not a blank page on which we can write our own version of what it should have been according to our contemporary views and prejudices.”

So, whose version becomes written history that makes for non-ideological educational content? As per the bitter remark made by American confederates following the Civil War, history is written by the winners. The fact that it is not a blank page actually means it’s more of a palimpsest - which has gradually erased all other perspectives, as it accommodated those of the winners. This, however, doesn’t make it any less ideological, or more prone to being taught as objective; it does, instead, reveal it as a power privilege. This singular version of history is what the well-known Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie dubbed "the danger of a single story". The protesters who ask for the removal of statues don’t seek to rewrite history, but to validate the perspectives of the colonized and exploited populations and of the descendants of those sold as slaves in the trans-Atlantic trade; in other words, of those long considered “people without history”, as (written) history only mentions them from the point of view of the colonizers, plantation owners, and slave traders.

Thus, political correctness is not a form without substance, but the logical consequence of a biased - and consequently politicized - historiography. After most colonized territories attained their independence in the second half of the 20th century and former ‘colonial subjects’ became postcolonial immigrants in Europe and the United States, this historiography could finally be contested.The history of the colonies never existed outside the history of colonial powers, but was living proof of the interdependence generated by colonialism and imperialism. As early as the 1980s, demonstrations against immigration restrictions and the limitation of the rights of African, Asian, and Latin American immigrants to Great Britain unfurled under the brief, yet comprehensive motto “We are here because you were there.”

Also in the 80s, another wave of demolitions, torn down monuments, and removed statues marked the transformation of Eastern European state socialism regimes, as well as a claim to recover the region’s repressed perspective on history. Removing Lenin’s statues in Berlin, Bucharest, Sofia, or Nowa Huta, tearing down the Berlin Wall, Marx’s statue in Budapest, or that of Romanian communist leader Petru Groza in Bucharest symbolized the passage from dictatorship to democracy and rewriting history onto the same palimpsest page, but by a different author. The former socialist countries saw the political regime and the symbolic register represented by state propaganda iconography undergo a simultaneous change in 1989, many other populations never had such a ‘year zero’ of reconstruction, on both political and symbolic grounds. Gaining state independence was not followed by the removal of monuments dedicated to dictators, nor by redrafting school curriculums from the perspective of the former colonial subjects. This is why we are witnessing a series of protests that, aside from judicial reform and material resource redistribution, are also demanding a recalibration of the symbolic register, which needs to reflect more than “a single story”. Throwing the statue of slave trafficker Edward Colton into the water is inscribed into such a recalibration, as it reflects Colton’s orders to throw rebelling enslaved people into the ocean. But it is also a recalibration to preserve Bismarck’s towers, as per German historian Jürgen Zimmerer’s proposal, to symbolically surround them with barbed wire, in order to evoke the concentration camps Germany operated in its African colonies, during Bismark’s chancellorship of the German Empire. As things stand, many plead not for destroying ambivalent statues and monuments, but to critically amend, recontextualize, or move them into specially designed and appropriately curated museums.

Romania’s socialist symbolism was also subjected to such critical recontextualization; some of the best known examples are putting Lenin's statue 'to sleep' by its former pedestal in front of Bucharest's Press House. Yet, far less discussed in Romania and the rest of Eastern Europe are statues and monuments associated with the history of colonialism, imperialism, and the Holocaust/Porajmas. Although the current protests and debates are largely taking place in the West (of Europe, but of the entire world, too), the East has been a part of - and a participant in - this global history. After 1989, when Romania reclaimed its francophonie, it prominently placed a monument dedicated to General Charles de Gaulle in the eponymous square outside Bucharest’s Herăstrău Park. With no other context, the monument only stands to remind us of the role de Gaulle played in the resistance against Nazism, yet not of his responsibility toward many of the victims of the 1945 French military intervention in Vietnam and in the Algerian war of independence, which ended in 1962. It is telling for the need to incorporate more perspectives that the current Charles de Gaulle Square had been named Adolf Hitler Square by Ion Antonescu in 1940 - and renamed into Generalissimo I.V. Stalin Square after the 1947 abolishment of monarchy. Paradoxically (or not), several Romanian towns unveiled statues and busts of Ion Antonescu in the 1990s - they were later prohibited by law after international protests against Antonescu’s responsibility in the Iași massacre of Jews and the deportation of the Roma population to Transnistria. Yet they still stand on private properties in Bucharest and elsewhere. History is not synonymous with collective memory. The question is: who has the right to remember?

Main photo: The statue of Belgian King Baudouin in Brussels, paint-bombed by protesters. Badouin played an important role in the extremely brutal colonization of the current Democratic Republic of Congo by Belgium, a country which has seen an increase in antiracist protests against statues, especially since June 30 is Congo’s Independence Day. Photo: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutterstock

Translated from the Romanian by Ioana Pelehatăi