In South Korea, a radical feminist movement called 4B tries to completely reshape patriarchy by rejecting any kind of relationships with men. What made thousands of women make this life changing decision and what consequences does it have within Korean society?

In May 2016, a Korean man stabbed to death a 23-year-old woman in a restroom in Gangnam, a rich neighborhood in Seoul, famous for the K-pop hit Gangnam Style. Surveillance footage showed that the man had waited in a unisex toilet near a metro station for more than an hour. Several men entered and exited the restroom during this time. When a Korean woman stepped in, he stabbed her in the chest four times with a kitchen knife. The perpetrator, a 34-year-old bar worker, explained to the police he felt “ignored and belittled” by women his entire life, when asked why he had chosen a female victim.

The crime became known as the Gangnam Station Murder Case, sparked a series of protests and was one of the major contributing forces for the 2015-2016 feminism reboot in South Korea.

South Korea is the 14th largest economy in the world, known for its huge music, film, cosmetics and tech industries. But the country also has a strong patriarchal culture. South Korea has the highest gender pay gap of the OECD members, at 31.2%, almost triple the OECD average of 11.6%. Women represent only 5% of boards in South Korea's corporate world. In a 2023 survey, 11% of women stated they had received unwanted sexual advances in the workplace, whereas 3.4% of men said the same.

Korea has “strong familism and Confucianism,” Jin-Sol Park, a 32-year-old feminist researcher, explains, referring to the ancient Chinese belief system, which has loyalty and respect for family as some of its core values. It’s a society accustomed to prioritizing community over the individual and women have always had a weaker voice than men, as mothers, wives, and daughters, Jin-Sol Park says.

The 2015-2016 activism resurgence contributed to the popularization of feminism in South Korea. In a 2019 survey, almost halfof the Korean women in their 20s said they identified themselves as feminists.

At the time of the Gangnam Station murder, Jungyeon Lee, a 33-year-old feminist researcher, was just about to graduate from a journalism program in Seoul. The societal reaction, especially from men and the police, who denied it was a hate crime, citing the man’s mental illness, made her angry. She was also angry that she didn't know much about feminism. Or gender based violence. Or sexual discrimination. She felt betrayed. “By society, by people who wrote textbooks, by politicians who are in charge,” she tells me one May morning in a Zoom call. It's been a week since I returned from South Korea, where I started reporting on this story. She was out of the country at the time, so we couldn't meet in person. Now, she looks at me from the screen: she has long curly hair, round framed glasses and she often smiles.

“Four No's”

In 2016, the incidence of intimate-partner violence in South Korea was 41.5%, compared with the global average of 30%. The same year, more than 5,000 spycam related crimes took place in the country. In Korea, hidden cameras (known as molka) are often set in public toilets, women’s locker rooms or hotel rooms, and they usually target women. Molka crimes in South Korea go unreported or undetected, and suspects are often not sentenced.

After finding out how many Korean men were sharing videos filmed by hidden cameras and how common violence against women was, Jungyeon felt she couldn’t brush this off. “If I get to have an intimate and sexual relationship with men, it is very likely for me to be a victim of gender-based violence,” she recalls thinking at the time.

She started spending hours on Twitter and online feminist communities. A search engine called Daum offered online safe spaces, called cafes, where people could gather and discuss certain issues. She and other young Korean women would meet online in cafes like AllFem or Ladism, where they could speak about their struggles and envision solutions.

One day in early 2017, Jungyeon came across several messages from Korean women suggesting they shouldn't have sexual or close relationships with men anymore. “That’s always how men control women in South Korea, by sexualizing and domesticating women, by putting women into certain roles as girlfriends and sexual partners,” the messages said. The proposal had a name: 4B.

4B means “Four No's” in Korean: bihon (no to marriage with men), bichulsan (no to childbirth), biyeonae (no to dating with men), bisekseu (no to sex with men).

She had dated and had sexual relationships with Korean men before hearing about 4B. And “it was okay,” she says. “I didn't feel [anything] especially violent or rude or anything like that.” But she always tried to fit traditional gender roles in her intimate relationships, she adds.

“Refusing any kind of relationship with men just felt powerful”, Jungyeon says about her first reaction when reading about 4B seven years ago. She currently teaches teenagers in schools in South Korea about gender-based violence and gender equality. She is also continuing her research and in the fall she will start a PhD in Gender and Women's Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.

She grew up in a middle class family and her parents never told her what she should or shouldn’t do because she was a girl. “They always taught me that I could achieve anything. And you should achieve something!”, she laughs, referring to the well known pressure of attaining success, deeply embedded in the culture of her country.

As a teenager, she thought women's rights had already been achieved and felt insecure that she wasn't pretty or skinny enough. “I wish I had learned that my body is not an object to fit into a certain size and shape and that my body and myself are not two different things,” she says.“I wish I could have seen my body as just myself, an organism that connects me to this world as I see it now.”

At 25, when she discovered 4B, she realized that “in any kind of relationship with men, women could be a bit in a vulnerable position.” So she decided to act. “I just wanted to do something about it. I just wanted to be part of something powerful. I wanted to make a change. And cutting every relationship with men seemed like an action that I could perform in my daily life. That's why I chose to join the movement.”

She stopped having any kind of sexual or intimate relationship with men. And gradually she ended up cutting her relationships with her male friends as well. It wasn’t something she purposefully did, she says, but she felt she could no longer communicate with someone who didn’t share the same values. She engaged in endless discussions about the Gangnam murder and many of her friends believed it wasn’t a hate crime. She first tried to persuade them by explaining “how this society is rotten” and how severe the crimes against women are. “It was frustrating and I was angry. Frustration was getting bigger than anger.” So she desisted.

4B is a movement that has been discussed and supported anonymously online since 2015, when the feminist reboot started in Korea, explains Jin-Sol Park, who holds a Master’s degree on the political meaning of the 4B movement. It is hard to measure how many members the 4B movement has gained, due to its fluid online and offline practices and its evolution along the years. Articles count between 5,000 and 50,000 Korean women who adhered to the movement. They refuse to marry, give birth, date and have sex with men.

“Their concerns were my concerns too”

Young women dressed in wide leg, skinny or short jeans, with crop tops and large shirts are walking in the green campus of the Ewha Womans University in Seoul. Ewha is a private women's university in Seoul, home to over 20,000 female students and considered one of the most prestigious universities in South Korea.

Men can teach and work in the maintenance of the campus, but they cannot enroll as students, Jin-Sol Park explains while we walk together on campus where she studied. Foreign male exchange students are allowed to enroll. “I don’t know why they come here. Maybe they are curious,” she smiles.

For her MA paper, Jin-Sol Park conducted in-depth interviews with a dozen 4B members and researched both their online and offline lives for over two years. “I am a member of the same generation living in Korea. Their concerns were my concerns too,” she tells me when I ask how she started her research. She witnessed domestic violence as a child in her house. She says she has been a feminist since she was 14 and had always felt alone until the feminist reboot in 2015-2016. She is not a member of the 4B community, but she strongly condemns gender based violence.

Before the Gangnam Station Murder Case, an online community called Megalia emerged in 2015 and became a strong feminist social movement (it shut down two years later). Members would post and “mirror” misogynistic content by reversing gender roles, provoking reactions that ranged from outrage to humor. Its logo was a hand with the index finger and thumb close together – a reference to a small penis.

Until that moment, Jin-Sol had to hide her feminist views from her peers and family. “If I said I’m a feminist, I could be attacked by many men, and I was truly afraid of psychological and physical attacks”, she recalls.

More than 77% of men in their 20s and more than 73% of men in their 30s were “repulsed by feminists or feminism”, according to a 2021 survey. Members of New Man on Solidarity, one of Korea’s most active anti-feminist groups (with over 500k subscribers to its YouTube channel founded in 2021) chant “Feminism is a mental illness” during the anti-feminist rallies they organise. Its motto once was “Till the day all feminists are exterminated!”

Through her research, Jin-Sol Park wanted to reveal the diversity and the multi-layered philosophy of the 4B community. “I was very curious about what kind of life they would lead. What kind of relationships will people create and live with?”

“Their political responsibility was impressive. They think they can change Korea by 4B practice”

The women Jin-Sol Park interviewed were in their 20s and 30s, and held various jobs, from IT specialists to teachers and lawyers. Some were college students. Some of them came from conservative families, where they felt discriminated against for being girls, while others came from supportive families. Some were Christian, but their religious identity came second. “«I am a 4B woman and, at the same time, I need to keep premarital purity»,” one of them told Jin-Sol. “«Religious things are important, but feminism is more important than religion»,” she added.

They had different views about embracing the 4B ethos. Some thought only Korean men should be boycotted. The new wave of feminists criticized Korea's patriarchal system also by comparing it to other countries, Jin-Sol explains. “For example, Swedish men spend more time doing housework than Korean men, awareness of wage discrimination in Western countries such as Germany and France is more developed, dating manners and femicide rates are lower, etc.”. Others thought all men should be subject to the movement.

“A society in which a woman is murdered in a bathroom and it is not recognized as a misogynistic crime and incidents where your intimate boyfriend secretly films your body and sexual intercourse and shares it with other men is no longer acceptable,” some 4B women told the researcher. “They boycott not only their sexuality with men, but also their country. (...) Online, many women said they wanted to apply for refugee status because of Korea's misogyny and patriarchal problems. Foreign countries may not be heaven, but it was popular to say that even heaven has levels.”

To be illegally filmed by a man. To be stalked. To get a sexually transmitted disease. These were the principal fears of the 4B women Jin-Sol interviewed. And they don’t want “to add the variable of men to their lives.” One interviewee used a candy jar as an example. “«If 9 out of 10 candies are poisonous, wouldn’ t it be safest not to eat them?»”

Beyond their personal reasons, the 4B women she met had a higher purpose. “They felt responsible for the next generation. They think the next generation will have a harder time if we don’t change the violence. Their political responsibility was impressive. They think they can change Korea by 4B practice.”

“With some relationships you can understand more about yourself. But it’s not a must.”

“4B is natural. I think it’s a survival strategy. I think it is hard to find the reason for marrying a man, to give birth,” Hye-Min Oh tells me at a coffee shop in Seoul. She is a 39-year-old lecturer of Artists’ Gender Training and Introduction to Feminism courses, at Korea National University of Arts, a co-ed university. “In marriage there is discrimination. It’s already hard [for women] to survive in their job and they don’t have time for household work.”

Hye-Min Oh describes herself as 1B (bihon - against marriage). Ten years ago she was considering marrying a man. But then she visited his family. It was the first time they had ever met and she remembers they only asked her about household and baby carrying. Nothing about her dreams and her career. After revealing her thoughts to her partner, he told her she had emotional issues because of her father, who was beating her as a child. She was shocked he used her trauma against her. “I was totally sick about that.” He also showed signs of violence and, after she broke up with him, he stalked her for six months, she says. “From that moment on, marriage is not my thing anymore.”

I ask her if she believes in the possibility that one day she might find a man who respects her and whom she might find right for her. She hesitates. “It’s possible,” she smiles. “But I live in Seoul. I meet only Korean men. It’s not my topic anymore. That’s why I understand the 4B movement. It’s quite natural for women. I would like to define this movement as a peaceful strike.”

Some of her female students confide in her during one-on-one sessions, saying that they don't want to date or marry men and seek her advice. “With some relationships you can understand more about yourself. But it’s not a must. I always tell them. Especially with someone who is not a match.”

She makes efforts to listen and understand her male students as well. How come some of them believe feminism is mental illness or cancer? How come some people call feminists feminazis? “Every semester I read this term [in written papers] in the obligatory class.”

Many male students ask her during class, “«Why is army mandatory for men and for women not? It is not equal. It is discrimination towards men».” This is the main reason for disputes between feminist and anti-feminists in South Korea. “Yes, it is discrimination,” Hye-Min Oh answers her students. “But it’s not women’s decision. Men did that, they made this decision.” In South Korean law, all able men must perform 18 to 21 months of military service. Suicide has been the leading cause of death among Korean soldiers for the past 10 years, the country’s Ministry of National Defense reported in 2021.

Young men look up to conservative politicians like Lee Jun-seok, the former leader of right-wing People Power Party, and Yoon Suk-yeol, the South Korean president. Yoon Suk-yeol won the 2022 elections with a message that blamed feminism for Korea’s low birth rate (0.78, the lowest in the world), and a promise to abolish the country’s Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. The Ministry was created in 2001 and its focus is the protection of sexual and domestic violence survivors and creating policies that do not discriminate based on gender.

*

I ask Jungyeon Lee if she had to hide she was part of the 4B movement. “For me it wasn’t an identity. It was just an action,” she says. And sharing this with her family wasn’t an issue anyway. “With family in South Korea, we don't talk about sex. I don't want to imagine my parents having sex and I don't want to imagine my brother having sex. Of course they will. But I don't want to think about it.”

Practicing 4B can be respected by others as a lifestyle, as long as the members don't use the word 4B when introducing themselves, researcher Jin-Sol Park believes. Many people associate their practice with the low birth rate in Korea, and they think they are responsible for the “disappearance of Korea,” she says.

“I am a very sexual person,” Jungyeon answers, when I ask how her sexual desire played into her decision to become 4B. “I just masturbated,” she laughs. “I was generally angry about Korean men and I didn't really want to talk to any Korean man. So when approached, I just ignored them.”

“Maybe I am not a typical 4B member anymore”

In October 2019, two years after she joined the movement, Jungyeon started a relationship with a woman. She knew she was bisexual, she says, but that was the first time she was in a relationship with a woman.

In the online debates she was taking part in, there were many heated discussions. One of the most sensitive issues was whether or not to engage in any form of intimate relationship, including with women. Many community members strongly argued they shouldn’t. Their main argument was that when you are in a relationship, you prioritize the other person. And as a radical feminist, you should prioritize yourself, in order to be more successful in society. The more successful women there are in a society, the more decisions will be made by women. And that was how Korean society could be changed to the better, they said.

Even though she didn't fully agree with that reasoning, she was familiar with the topics. So when she started a relationship with a woman, she thought: “Okay, I may not be a person that they will welcome when I go to some kind of online community. Maybe I am not a typical 4B member anymore”.

“Those two parts of the world were very different and I was a part of both worlds”

Jungyeon enrolled in a Master's degree in women's studies at Ewha Womans University. The offline community she encountered there was different from the online one, she remembers. The people she met were open to relationships. “After seminars we used to go to a bar and talk about having sex with women all the time,” she laughs. “Those two parts of the world were very different and I was a part of both worlds”.

“Right now it seems like I can't call myself a 4B member [anymore] because I am not cutting relationships with men anymore,” Jungyeon tells me. She recently realized that avoiding sexual relationships with men proved not to be such a good decision, because she is a sexual person.

She is still afraid about being filmed against her will or becoming a victim of sexual violence. She doesn't do it on purpose, she says, but she instinctively avoids Korean men. “When I'm in South Korea, when I walk on the streets and when I see an attractive man passing by, I kind of think: He might be an active member of an anti-feminist online community. And when I think about that, the attraction just fades away”.

“4B is for myself, for society and for young girls”

Another big feminist movement in South Korea, besides 4B, is called “Escape the Corset”, which was founded in 2018. Women who support it cut their hair short, threw away their makeup, and renounced any kind of beauty practices in a country that has one of the biggest cosmetics markets in the world. In 2021, South Korea exported $9.2 billion worth cosmetics, making South Korea becoming the third largest exporter after France and the United States.

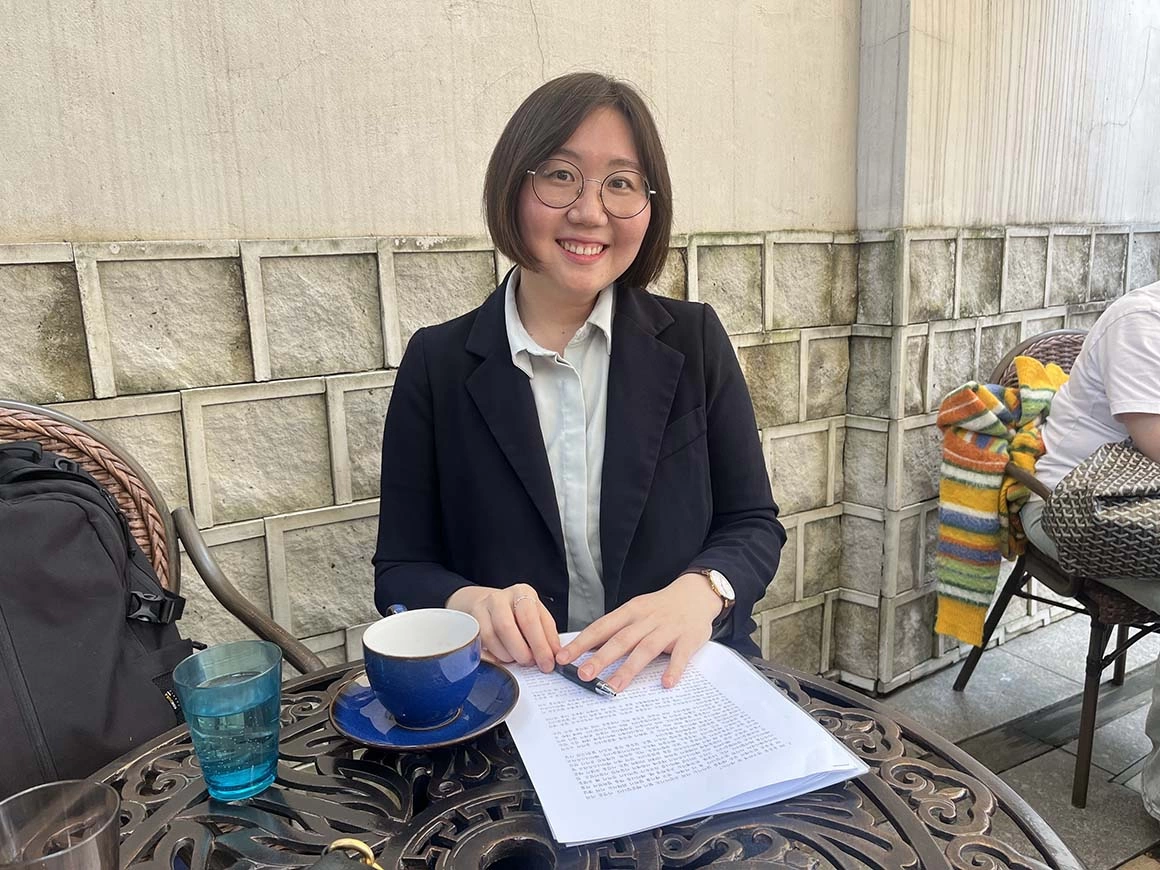

Gaeul Baek, 34 years old, the founding editor of the radical feminist magazine RADish and a 4B member, cut her hair short during one of the 2018 Hyehwa Station protests against sexism, misogyny and hidden camera voyeurism. The protests sparked after a woman was arrested for secretly photographing and exposing online a male nude model after they had a fight. Activists argued that police made a quick investigation and arrest only because the victim was a male. Hyehwa Station protests are considered the largest feminist protests in South Korea, reaching 110,000 participants by December 2018.

Before the protests, the organizers recruited women who wanted to cut their hair on the day of the rally, Gaeul explains. As she closed her eyes and waited for a volunteer to pass the scissors in her hair, she could hear thousands of women in the march shout “real women” or “awesome”. When other women who cut their hair as well shared their stories on the microphone she cried along with them. The feeling of “upliftment and unity” she experienced that day is unforgettable. She still keeps the hair she cut at the protest. “It is my proud flag of liberation”, she says.

Gaeul was born in the early 1990s, the height of South Korea's “son preference” ideology, known as gender biased selection. (Sex-selective abortions are encountered in countries like China, India, South Korea, Vietnam, as well as in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia.) Despite the abortion being criminalized at the time in South Korea, it was largely practised at family planning centers.

“There is a saying in South Korea that the third male child in that generation was born after killing his sister”, Gaeul says. “Literally, it was a generation that died before they were born because they were women. The parents of this generation favored their sons and were mean to their daughters. I come from that generation”, she adds.

In a society where romance, marriage, and procreation are expected from women, the 4B movement is a declaration, Gauel explains. “That you want to live your life for yourself, not just for your husband and (future) baby. It's a declaration to live fully as yourself, not as a reserve.”

Some people think that 4B is just about excluding men, Gaeul points. But 4B is more than leaving men behind, it is about living with other women. “Most of my friends are feminist women who practice the 4B’s like me. We organize seminars, go to rallies, travel together, and share vegetables from our garden.” They do political activities together and discuss feminist teaching methods. The majority of them are active on social media and engage in feminist discourses. “This is a demographic group that actively shapes public opinion and drives change in Korean society”, she says.

Gaeul Baek is also a teacher of science and technology in a highschool in Seoul and she wants her students to know that there are adult women “who don't decorate themselves” and don't get married. “4B is for myself, for society and for young girls,” she says. She is concerned when she sees how easily young girls can become vulnerable to digital crimes, when dancing to K-pop music scantily dressed and posting their videos on Instagram and Tik-Tok.

“I'm not cutting off any more relationships with men”

At the moment, Jungyeon Lee says she sometimes browses feminist platforms, but she is not actively engaging in conversations. “I am not that angry right now.”

Feminism is still one of her fundamental ideologies, but she no longer avoids conversations with people who are not feminists. “I think this may sound very arrogant, but I tried to change everyone.” She has come to accept people have their own backgrounds and feminism does not mean one single thing for everybody.

She now believes that it is possible for people to hold different views and still build meaningful relationships with each other. “Now I think communication is more important than just trying to change someone”.

She says she also has a better relationship with her father and brother. In the past they would often argue and she would judge them, she remembers. “And I was getting hurt at the end”. She still tries to persuade them from time to time, but she tries to avoid words like feminism, sexism, and discrimination. She says she wants less arguments, and more listening to each other.

Anti-feminist male online communities supported by right-wing politicians are a real concern for Jungyeon. Her research will focus on the role emotion plays in online debates and in shaping people's ideas. “Women especially try to persuade men by language, by logic, by words, but it seems it is not very effective”, she believes, after being engaged in this activist work for a few years.

*

After the Gangam murder brought feminism back on the public agenda in South Korea, a national digital sexual crime prevention center was established in 2018. It offers counseling to victims, helps getting illegal videos erased and offers investigative support. Abortion was decriminalized in 2021 and many of the women I spoke to think awareness of misogyny has improved. “Of course, the backlash is strong. However, there are people who have hope in the rapidly changing Korean society,” researcher Jin-Sol Park concludes.

Epilogue

“Delia, why are you doing this story?,” Jin-Sol Park asked me when we left the Ewha University campus, before saying goodbye to each other.

In the last few years I have constantly asked myself both in my work and my personal life: What can we do so we come more often towards each other as human beings? When I don’t have the answers I try to look at the ones who chose to give that up. Seeing how we got there is a precious hint.

*

The reporting on this story was possible due to the participation at the World Journalists Conference in South Korea, organized by the Journalists Association of Korea (JAK), between April 21st and 26th 2024. After the conference I stayed in Seoul and reported on this story until May 3rd.

MAIN PHOTO: Gaeul Baek after cutting her hair during the Hyehwa Station protests against sexism, misogyny, and illegal filming (molka). May 2018, Seoul, South Korea. Photo from her personal archive. Credit Photo: The courage to be uncomfortable