I am talking with a friend of mine. She volunteers in a transit camp in Bucharest’s main railway station, Gara de Nord, for Ukrainian refugees fleeing the Russian attack. I ask if I can help. She tells me that after 10pm, many volunteers catch the Metro home, yet Ukrainians are still arriving, so I sign up for the late shift.

On the station’s main concourse is a blue tent, run by Bucharest City Hall. Here, volunteers receive a yellow vest with the Ukrainian flag, and translators receive an orange vest. Nearly all the volunteers are from Romania, and the translators are mostly from Moldova and Ukraine.

At the tent, I write my name on a clipboard, and the guys from City Hall ask for my ID. I bring out a flashy ten-year British passport. As I flip this open to show my details, slime splatters against my photo. A gob of filth drops on my back. I look up. A pigeon flaps through the rusty girders.

“It’s good luck,” says one of the guys, handing me a wet tissue, to wipe the shit from my face.

Our job is to pick up Ukrainians leaving trains and buses, carry their luggage, ask if they have a place to stay, and find them rooms with the assistance of the fire brigade. If the refugees want to travel further, we help them buy train tickets. One Ukrainian volunteer tells me: “It is like a computer game. I must explore the territory, find people, deliver them to another place, and solve problems.”

“But who gives you rewards?” I ask.

“I have to give them to myself.”

Most of the Ukrainians come over the border in the north or from the southeast. When their trains arrive, the platforms are dark. Panels in the roof are broken. Concrete pillars holding up the building are crumbling. Passengers exiting the carriages try not to fall down the steps. Almost everyone looks lost, and confused.

The volunteers wander down the platform, shouting ‘Ucrainenii?’ [Ukrainians?], but if no one responds, how do we recognize refugees? One sign is when passengers have too much baggage to manage alone. Another giveaway is if they carry cats or dogs, either in plastic boxes, or loose on a leash. Sometimes their suitcases are broken. The wheels do not work. The handle is frayed. The wire frame has decoupled from the rim, and flaps dangerously. I used to wonder why people don’t throw away suitcases, even if they are broken. But for those who live in the middle of Europe, this is common sense. Because there may be a time when we need them, and a damaged suitcase is better than no suitcase at all.

“I can’t think about hate”

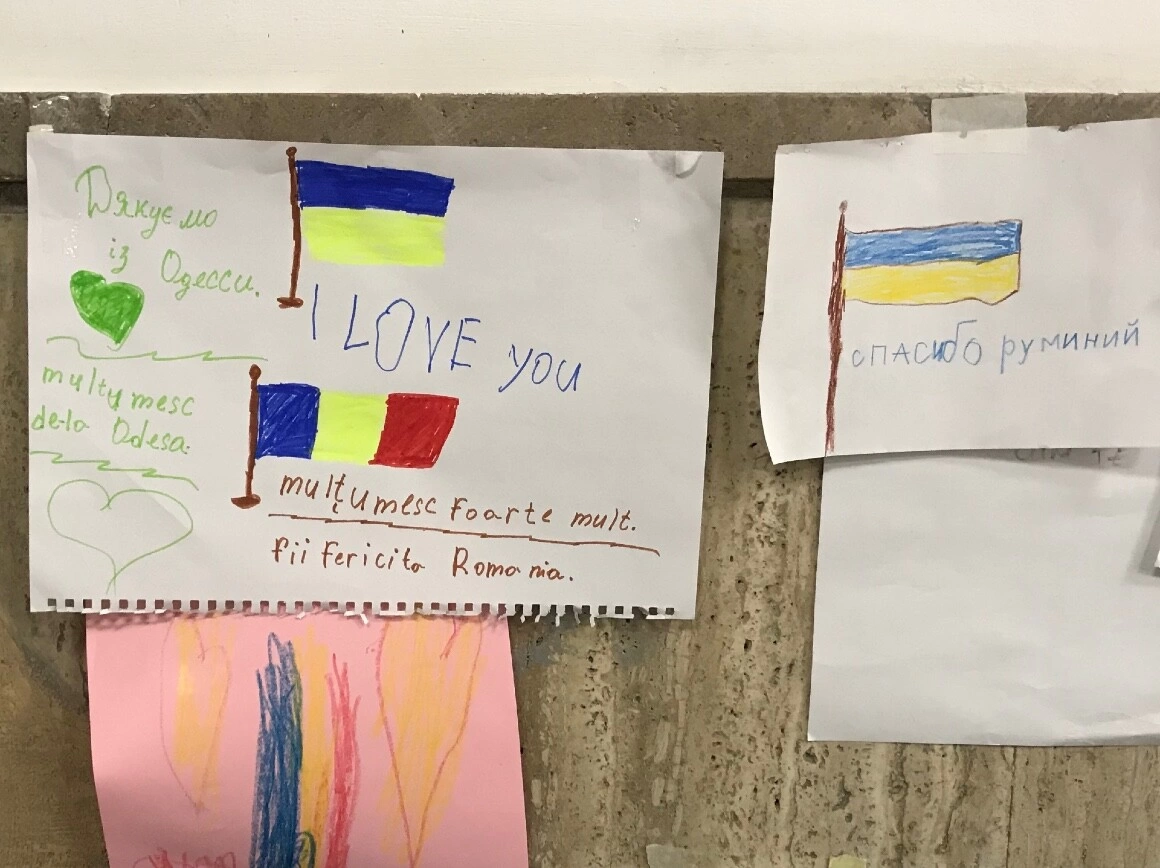

Most of the refugees come from the southern towns of Odesa, Melitopol, and Mykolaiv, which were heavily bombed by Russia. Others are from Kyiv, and are transiting through Bucharest’s airport at Otopeni. There are also a large number from the region around Chernivtsi, which was part of the Romanian state between 1918 and 1944, and was in the territory of Moldova before the 18th century. Many have come south because there is a historical link, even if it has struggled to survive through the generations.

One 60 year-old woman is travelling to Budapest. A Moldovan volunteer finds out she is from Chernivtsi, and asks in Russian:

“Don’t you know Romanian?”

“No,” she says. “We never learned it.”

“Nothing at all?”

“Nothing, except Drum Bun.”

In English, Drum Bun literally means ‘Good road’, but can be best translated as ‘Have a Safe Trip’. It seems the only words she remembers, in the language of her former rulers, are how to say goodbye.

Many of the children do not speak. I see a woman holding the hand of a boy, aged eight or nine, as they walk to a minibus to take them to a place to stay. I carry the luggage. She follows the firemen. The boy is silent. I have never seen someone hold another hand so tight as his mother. Every muscle is taut. She will not let go. I don’t think she ever wants to let go.

Many are on their way to Germany, Bulgaria, and Slovenia. I want to ask them questions: You’re from Kyiv, please tell me about the massacre at Bucha. You’re from the south, what’s happening in the siege of Mariupol? Did you hide in a shelter underground? Are your husbands or fathers at the frontline? Part of me wants to shake down these victims of history. On the day the Russians bomb Kramatorsk station, killing dozens of children, I ask one Ukrainian if he saw what happened?

“Yes.”

I am about to ask more. I can’t. There are no more words. They are fleeing war. They don’t want to talk about war. This is the one place we don’t talk about war.

When I ask another Ukrainian if he hates Putin, he tells me:

“I can’t think about hate. Only about what I eat and where I stay.”

They need a bed today, and a bed tomorrow, for them and their children. A room that is warm, and food. They need the Internet. Their cats must stop shivering, and vomiting. Their dogs must be quiet. All else is distraction.

Denying food to Ukrainians: Bad Idea

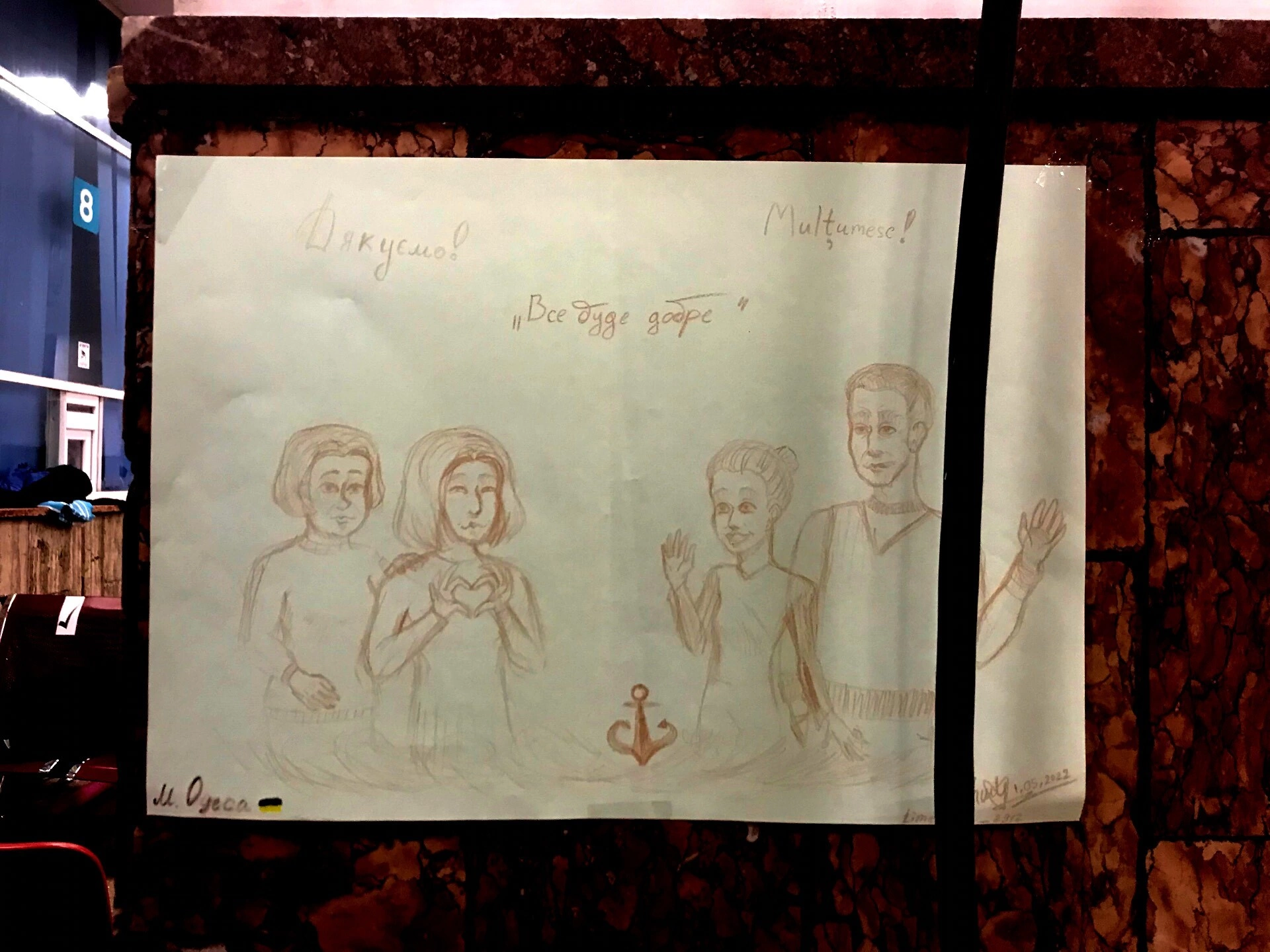

The main ticket office is now transformed into a waiting room and canteen for refugees. It is lined with black office chairs, some of which are broken and covered in cat hairs, and fold-out beds for those who want to sleep. In the corner are soft toys, Lego and a green carpet of a cartoon city with traffic, parks and tower blocks. Behind the play area are children’s pictures of unicorns and stars, dolphins, trees, hearts, and Ukrainian flags. Here are tables of free food, drinks and cleaning products for the refugees. There are packaged meals of pasta with fresh basil, chicken legs, and fried cheese in breadcrumbs, which can be heated in a microwave, bottles of water, chocolate croissants, and M&Ms. I come in one evening and find a pile of copies of the New Testament next to a basket of apples and bananas. Their covers are in black leather. The name appears in four languages: Italian, English, French, and German. Not Ukrainian. Not Romanian. Not Russian.

A Ukrainian mother comes in, with her two teenage sons, and she asks for a bag. I pass one to her, and she fills this up with bars of rum-flavored chocolate, bread rolls, orange juice, and a couple of meals. I worry there will not be enough for the other refugees, even though this family looks cold, and hungry. But I hold back from speaking. Anyone familiar with the history of this region in the 1930s knows that to deny food to Ukrainians is not only immoral, but perpetuates a historical wrong that Europe has yet to atone for.

Sometimes the refugees are angry. Sometimes they are annoying. But there is also a delusional aspect, which touches on both trauma and fantasy. One volunteer tells me she was speaking to a family from Ukraine who were on their way to Switzerland. She asked them: do you have family or friends there? No, came the mother’s reply. Do you have a job there? No, said the mother. Then why are you going? Because we saw pictures of the Swiss landscape, and it looked beautiful.

Another woman comes into the ticket office, and I make her some tea, and she asks if there is someone who can give free English classes to a friend of hers. Some religious groups offer this service in the city. Why does she want to learn? I ask. The woman has to learn English, because she wants to go to Australia, and she found out that in Australia, they speak English.

An office manager from Kyiv has a long discussion with me, where she wonders which is the best country in Europe for her to settle. The UK is too hard for her to enter. In Italy, she won’t find a well-paid job. In Ireland, she can’t afford a place to stay. She ponders over France. “I listened on my phone to the presidential debate between Macron and Le Pen,” she says. “I didn’t understand a word, but the language is so lovely.”

This is not their fault. Many have never left their country before now. They are not sure of the scope of what is possible, and what is impossible, as a refugee. It is not clear to them. To be honest, it is not clear to us.

The Station that Fills with Water When it Rains

Gara de Nord is a miserable place. It has always been a miserable place. It used to be a scary, unsafe, dirty and miserable place. Now it’s safer and cleaner, but it’s still scary and miserable. In the past, I’ve been robbed here, and I’ve been punched here. Passengers leaving the train at night can’t see where they are. The signage is obscure. Everyone who can help is hidden behind glass windows of ticket booths, which makes communication tough, and often inscrutable. Whenever volunteers are on the concourse, random travelers come up to us, and ask about the next train to some faraway city, where to change money, or where to get a bus to a hospital, or a market. Because we wear hi-vis jackets, they think we have the information they need.

When it rains, there are so many holes in the roof, the concourse overflows with pools of water. The station should be non-smoking. But in every corner, behind every kiosk, and on every platform, huddle packs of smokers. At the front entrance, drunken tramps argue with one another. Crowds of homeless queue for free soup and sandwiches from a van. Outside on the window ledges, red-eyed boys in filthy coats crouch over plastic bags of paint-thinner, inhaling the contents for a dizzy high. When I wheel some baggage for a Ukrainian family to a local hotel, a scraggy-haired guy with a dirty face shakes his head at me, while dragging a broken foot, and shouting: “I’m gonna break your glasses! I’m gonna break your glasses!”

On the night of Good Friday, as I enter the station, a man shuffles up to me. He has no front teeth, and is wearing a shepherd’s cap, loose at the back. He presents me with a plastic box, containing a huge red dildo.

“You want?” he asks.

It isn’t clear whether he is selling this to me, or is suggesting we should use it together. Between these two options, I hope it is the former. Nevertheless, I politely decline his offer.

When I am making tea for refugees in the ticket hall, two women with long curly hair and wide grins enter the room. Around their necks hang stethoscopes, and they are carrying small backpacks. In good English, they explain how they are nurses, from a charity in Israel.

“We have come to see if anyone needs us,” one of them says.

I look at the refugees in this room. Some are cold, some are sad, and some are worried, but they have food, clothes, and are not sick.

“There are people in this station who need your help,” I say, “but they are not Ukrainian.”

More Choice than America

When I arrive at ten at night, a middle-aged guy with a beard is giving out food and drink to the refugees. This is Troy, and he helps the underprivileged find jobs in Indiana. He flew several thousand miles to volunteer. He stands at the giant boiler, making tea. There are many boxes of tea. The refugees help themselves. Our job is to pour hot water and hand this to them. They can choose from black, yellow label, Earl Grey, green, and fruits of the forest.

“Wow,” Troy says. “You have so many types of tea here.”

“Don’t you have these in Indiana?”

“No.”

“What types do you have?”

“We have Lipton.”

On the main concourse lies the former fast-food restaurant Springtime, which used to sell kebab, pizza and chicken. This is now a warehouse for food donations, and a waiting room for refugees during the day. Diapers, shampoo, water, snacks, and meals are kept here. In the ticket hall, where refugees sit, I check what is missing. I notice we are out of sanitary towels. Because I have never needed these in Romania, I am unsure of the translation. I ask a volunteer, and she tells me: ‘Absorbante’, so I go to the warehouse to find some.

It is past midnight. The station is desolate. Washing vehicles are cleaning the floor of the concourse. I enter Springtime. Inside it is quiet and empty. An old cop in a silver mustache is half-dozing on a chair.

My presence wakes him up. He eyes me suspiciously.

I hold up the empty packet of Always Ultra.

“Do you have absorbante?” I ask.

“Huh?”

I try again.

“Absorbante for the Ukrainians.”

For a few seconds, we are silent, looking at each other, wondering how it has come to this.

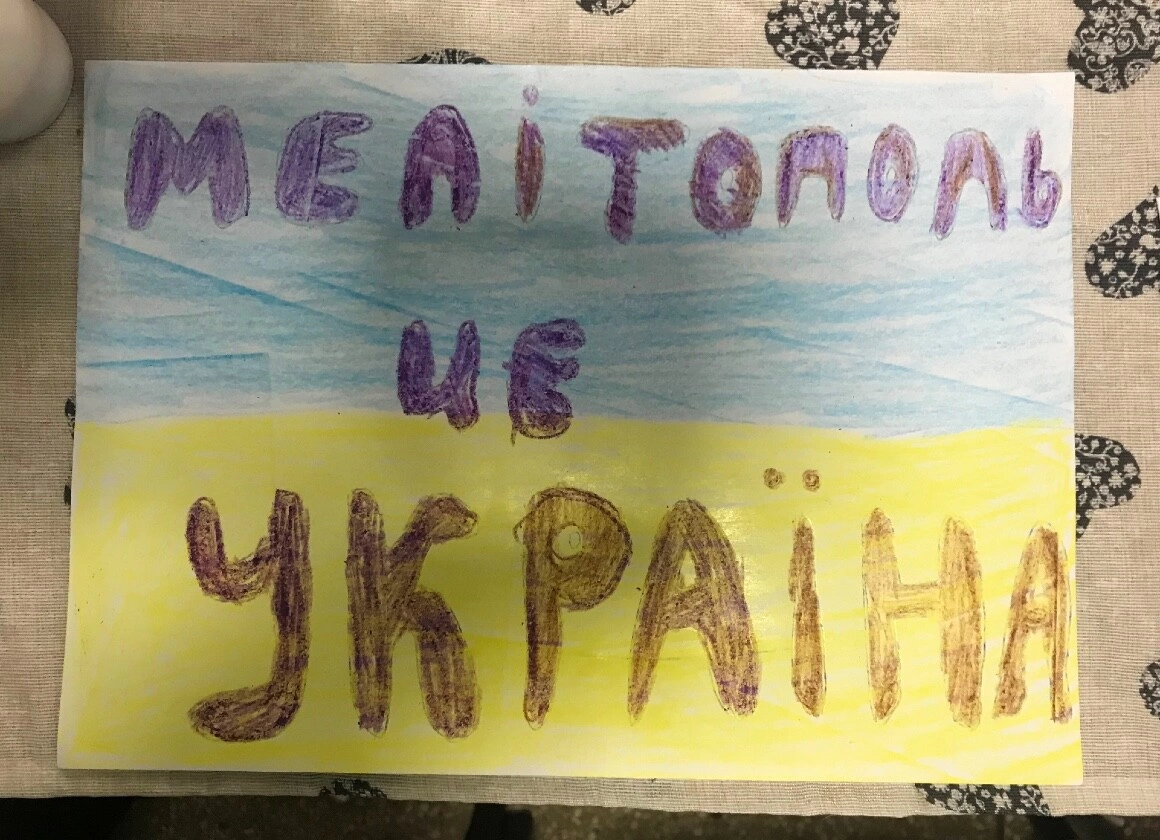

In the ticket hall, a boy of around 11 years draws a picture with blue and yellow crayons of the Ukrainian flag with the words ‘Melitopol tse Ukraina’. He comes to the tables carrying food, and hands this to a young and pretty Romanian student, working as a volunteer. She asks a Moldovan translator what it means, and he says it’s supposed to say ‘Melitopol belongs to Ukraine’, in reference to the city where he has come from, which is under Russian occupation. But the translator argues the grammar isn’t correct, and he needs to speak to the kid about this. As he carries the picture back to the boy, the student protests: “Don’t tell him. It’s my present.”

Highs school kids aged as young as 16 are volunteers here. They should be sitting in their bedroom, a window open, joint to hand, machine-gunning zombies on an Xbox, but they are handing out food and drink to Ukrainian refugees. They are incredible. But some volunteers are troubled. One guy refuses to move a chair or clean a table, with the excuse: “I am here voluntarily. I can do what I want.” Many leave after a few hours, and do not come back. Some are confused about why I, as an English person, am not only in Romania, but also in Gara de Nord. Others can’t work out who I am. One Moldovan volunteer points to me and says: “You have the face of someone who speaks French.” She isn’t convinced that I am French, but that I have the face of someone who can articulate the words. Language can distort an appearance. This is how I look. Like a man mutilated by the French language.

Ukrainian Roma Confuse People

Stories in the media have revealed racism among the volunteers in the station against the Roma from Ukraine. Whenever I am on duty, the Roma face equal treatment from the volunteers, translators, police, and fire brigade. But I see non-verbal signals. Slight frustrations. Old prejudices resurface. One Roma family comes inside the ticket hall, asking for food and drink. A mother places free yogurt and sandwiches in her bag. Her son picks up a handful of sugar-cubes. They start packing away the bananas. A Romanian volunteer is worried she is taking too many, and tries to explain this to her. There is some confusion over what this means in Russian. The volunteer becomes annoyed.

“Don’t try and tell me you don’t know Romanian,” she tells the Roma family.

Romania has always had a complex relationship with its Roma minority. In recent years, senior politicians have been trying to disown them, and claim they are distinct from Romanian culture, are nomadic, and are part of an issue that ‘Europe’ must tackle collectively.

Yet when some Romanians are faced with Roma refugees from Ukraine, they rush to claim common interests with them. They look like our people, so they must speak our language, they believe. In this case, the irony is they are becoming possessive over the Roma, in order *not* to assist them. Romanian citizens are forbidden from helping themselves to the free food and drink in the station.

As April turns to May, fewer Ukrainians are coming to Romania, and more are leaving to Odesa and back over the border in the north. But many are still arriving, and need a place to stay.

Sometimes, we fuck up. At midnight, a minibus is waiting outside the station to take a couple of families to their accommodation, and I ask the driver if they have extra spaces. The driver says yes. One translator and I pile in an older woman and her two adult daughters, who squeeze into the back of the vehicle. The bus leaves. We feel smug.

Then a young mother turns up at the station exit, holding the hand of a boy, no more than nine years old.

She asks where the minibus is.

We tell her it has gone.

The kid turns to his mother and says:

“Are we not going to the hotel anymore?”

The volunteers and translators are often tired. They work long hours. Unsociable hours. Many want to do more. Help more people. In more profound ways. But the refugees come and go. There are too many at once. And not enough at other times. Sometimes the volunteers have energy to assist. Other times they can only do the bare minimum.

“All I do is translate, and pick up luggage,” one young Ukrainian volunteer says. “I don’t feel I am doing enough.”

I think of my role over these last few weeks. It is much less important than him, and less important than nearly all the volunteers, who have given up time with their family and friends, and jobs and school, to be here. But I want to reassure him. Tell him what he is doing is worthwhile. “It may only be a small contribution,” I say, “but great things can only be made from many people making small contributions.”

I try to sound clever. It probably comes out patronizing. I doubt it helps. But it makes me think of the wider picture of how to help a neighboring country stricken by war. Sometimes we fail. Sometimes we face scorn. Sometimes we aren’t helping out of sympathy for Ukrainians, but because we want to feel pious, and self-important, or repentant. Our intentions are not always altruistic. Our motivations and the actions we take, are imperfect. But we have to try, even if it is no more than a small donation, such as a bag of clothes or a few boxes of biscuits, a message of solidarity, or sharing something online, because the only alternative is indifference, and that is a horror too deep and wide to dare encounter.