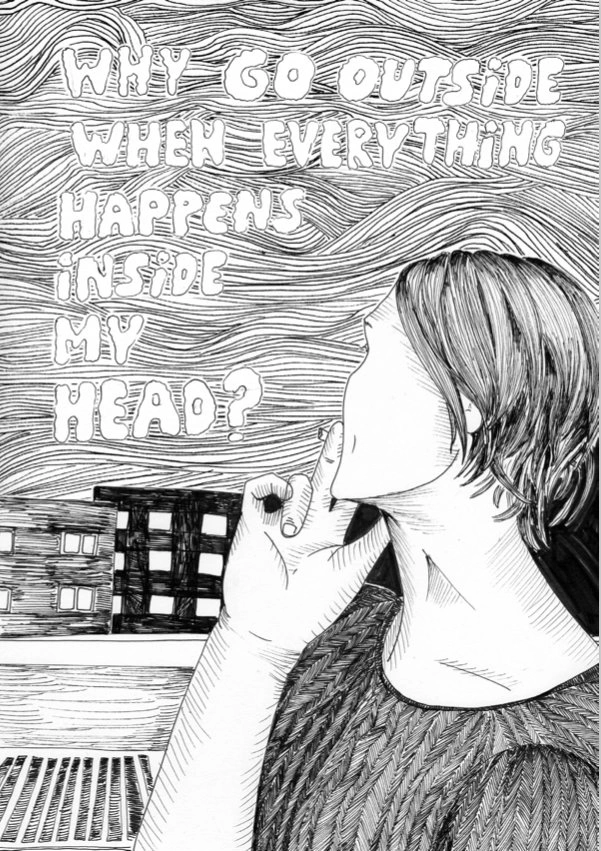

Have you ever woken up without wanting to get out of bed because you didn’t see the point of it? But you somehow did it and said To hell with it, I’m not going to go to work today, I’ll stay home and it’ll be OK, but it wasn’t OK? Were you ever bored and vaguely disgusted thinking of the previous night when you got hammered and now you’re feeling sick? Did you ever ask yourself what the point of you work is and whether or not it would be better if you just did something else? Or maybe nothing at all? Did you ever feel guilty for having first world problems? Did you ever hide between the covers, sheltered away from your fears? The fear of growing old? The fear of living in vain? The fear of death?

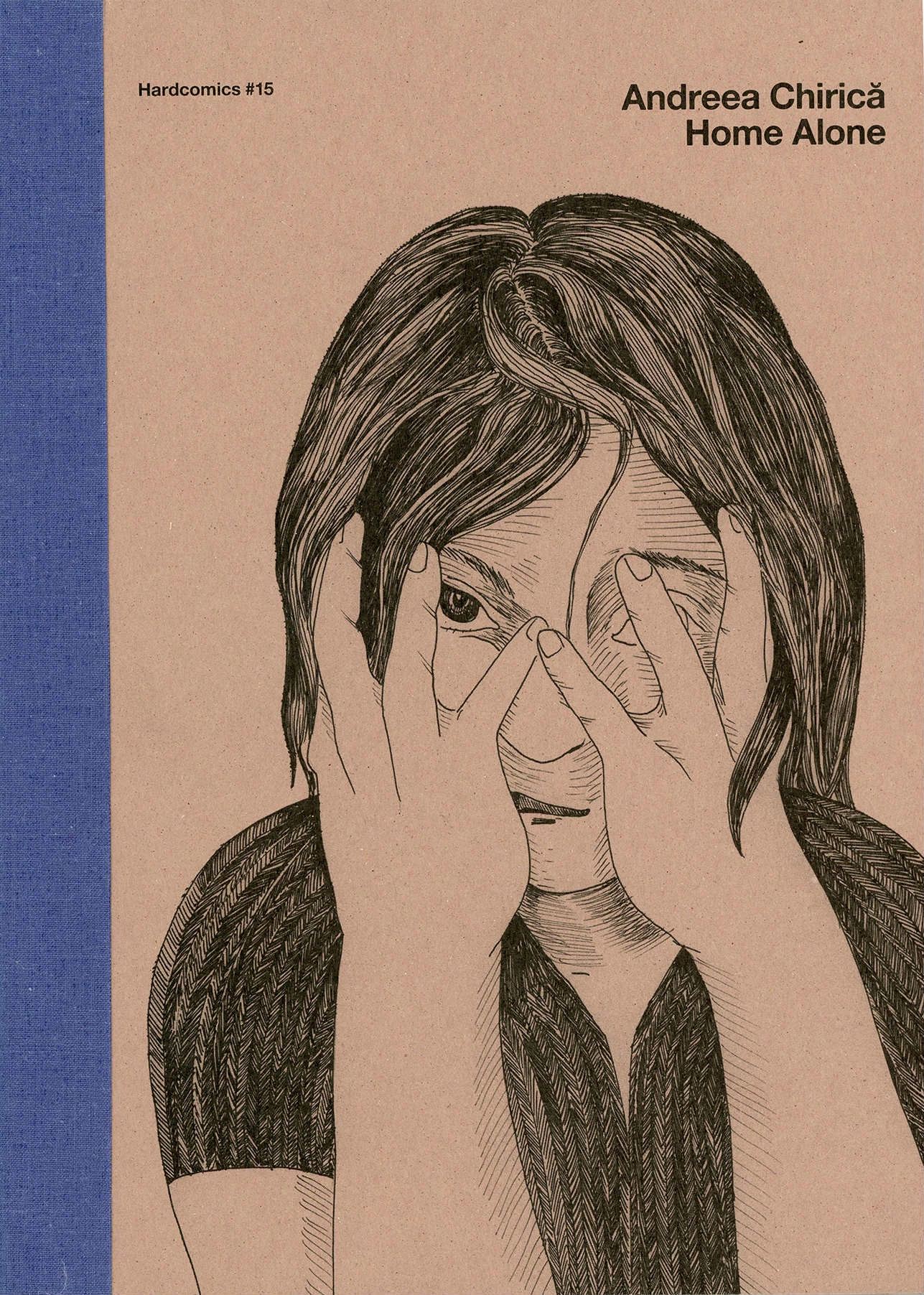

If you’ve answered yes to at least one of the above questions, then Home Alone is for you. In 100 and something pages of drawings, Andreea Chirică makes a journey of this sad world in a single day. She lets you go inside her room, through the window. She lets you look through her fridge, go through her drawers and her FB account, until you don’t know if Home Alone is about you or about her. All things considered, this novel – excuse me, this graphic poem, is in the top 5 Romanian books that were published last year. For a while, you could only find it in two bookstores in Bucharest. In the meanwhile, one of them shut down.

Andreea Chirică is 38, but she looks 28. She’s from Medgidia, she did theatre studies at UNATC and worked as a copywriter for a while. In 2008, she started a drawing blog, and in 2011 she put out a graphic novel, The Year of the Pioneer, a tender exploration of the a year of her life, 1986, when she was a pioneer. The novel features black and white drawings, with content written in a tender English.

She drew her first picture at the age of 28: “I was at the office and a couple of colleagues and I went to McDonalds. I drew us and our identical menus on the table. I sent it to them and they thought it was funny. This encouraged me to keep doing stuff. Then again, I don’t even know how I ended up doing this…”

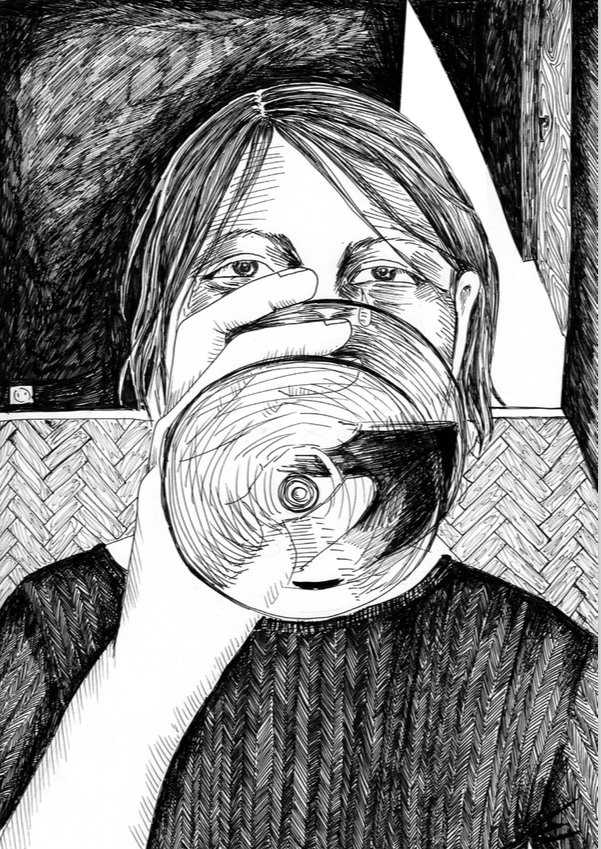

I envy her because she’s self-taught. In the past 10 years, she’s taught herself how to draw. She paid attention to lines, shadows, faces, and gestures. She’s always got a meta-discourse ready, about the fact that she’s someone-who-draws, in the process of becoming a full life illustrator. She’s asking questions, tries different things, but, most importantly, she’s doesn’t stop drawing. “I think anyone can draw”, she tells me from behind a glass of rose. “I think that you just need to like it, to try doing it. And if you like to scribble, in time, it will end up looking OK from a technical standpoint, and then you can start saying things with it.”

How did she learn how to draw? “I just looked around me. You get to understand lots of things, as you are doing them. You realize how the light shines while you are drawing, and it is a very good exercise, because you get to see things from a different perspective.”

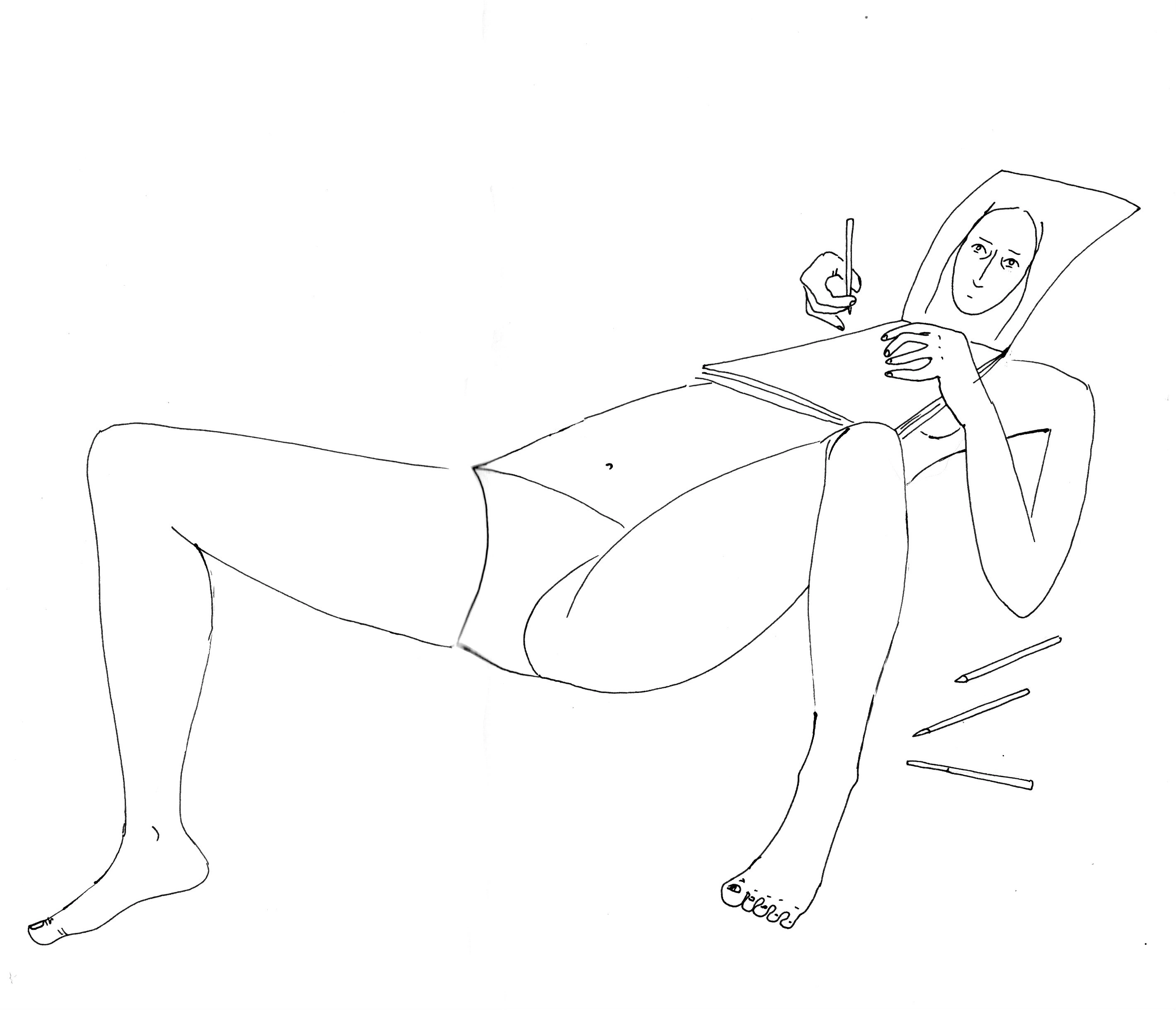

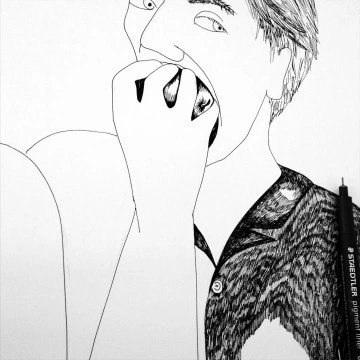

She draws on paper and then she scans it. “First, I use pencils, and then liners, and an isograph. And for larger areas, I use ink and a brush.” When it comes to Romania’s illustrators, she likes Sorina Vazelina („I like that she’s manic, she does a lot of details”) and Oana Lohan (she admires her because her work is very realistic). Internationally, she likes Amélie Fontaine, a French illustrator, but she’s annoyed at the fact that she rarely posts her stuff. “I should write to her and say that I like her, shouldn’t I?”

Andreea Chirică quit her job “like they do in the movies”. She got up from her copywriter’s desk and said: “I can’t do this anymore, I’m leaving.” And so that’s what she did. One and a half years later, she works with images, instead of words. Having changed her expression medium, she’s a freelancer. She says that “it was and still is quite difficult”.

A small publishing house specialized in comics and graphic novels, Hardcomics, published her two books. Small publishing houses are difficult to bring to big bookstores and even harder to reach an audience. The advantage, though, is that you can personalize pretty much everything, from the paper used to the cover itself. The disadvantage is that there are no shortcuts to your readers. “If you could make money from other projects, and finance your personal endeavors and still have the energy to do all of them…”

She tells me she’s a bit embarrassed of her first book, The Year of the Pioneer. “Because I don’t like how I drew it. It was a type of it’s clear that I can’t draw well, but I’ll do a book as a person who is a bad drawer, and I’ll live with that. But as soon as it was published, I was embarrassed. I said to myself why do I even do this when I can’t even… But then I realized that it was what I wanted to do with my life.”

Why? “Because when I draw, I feel great. I never get frustrated when it takes me a long time to do something, or when I mess it up. It’s just pure pleasure. Until recently, I didn’t even conceive that I could try drawing as best I could, try be better than a certain someone. I’m an outsider in this world. I draw all sorts of frustrations; I draw myself…”

I envy her because, pragmatically, she looks more towards the inside and less to the outside. That she has the courage to draw her fears, doubts, loneliness, depression and that, by making this uncomfortable choice, she ends up in places that all of us feel pain in.

Home Alone started with a breakup: “I broke up with my then boyfriend and I said, That’s it! I’m starting work on a second book.” It should have been a book about Tatars, about how one of Medgidia’s communities is slowly losing its language. But it came out something else completely: “I started working on the Tatar Book and I began drawing myself, feeling sad in my bed, and then I said to myself: Wait, it’s clearly what I should be doing. So I did that, but I wasn’t too consistent – you do ten pages and then you think to yourself Who needs whatever it is I’m doing? Why? It’s going to be something like “I feel sorry for myself” and I’ll show everyone “Oh, I’m so sad!”. But then I thought No, I’ll do this. I really wanted everything out in the open.”

She worked for two years on the book, especially on the weekends. Towards the end, she had the feeling that the dust was starting to settle on the project, so she finished it because “I’ve got this thing where I need to finish things, otherwise I feel them looming above me.” She wrote the last sentence – “Andreea finally falls asleep” – and sent the book to Miloš Jovanović from Hardcomics. It lasted another year until she got all the money together to publish it, “meanwhile, my hair grew”. I laugh and tell her that “you’re right, I was expecting you to look like Andreea from the book…”

Real life Andreea looks like book Andreea, just as you, the one reading this text, look like yourself when you were reading Cireșarii during the fourth grade summer break. Her identity is made up of fragments, and Home Alone plays efficiently with this fragmentation. “I don’t even look like myself from one page to another”, she tells me. “I didn’t keep the connection. It’s about a day, but it can very well be about many days. Or about a very long day, or a year even…”

I ask her why she chose to write on the fourth cover that it was a “graphic poem”, and not a novel: “I thought that people would have expectations of a narration, but I realized that desperation and sufferance don’t really have a narration to them. Images and poetry, are lot more incoherent when they manifest. Besides, the drawing inspired the text.”

The title is also caught in between two worlds: “When you are young, the idea of being home alone brings you so much joy, it’s an adventure. But when you’re an adult, it’s a spectrum. “I’m home alone” sounds exactly the same, but it means a completely different thing. I loved this contrast, which I find quite self-ironic. So bitterly, self-ironic.”

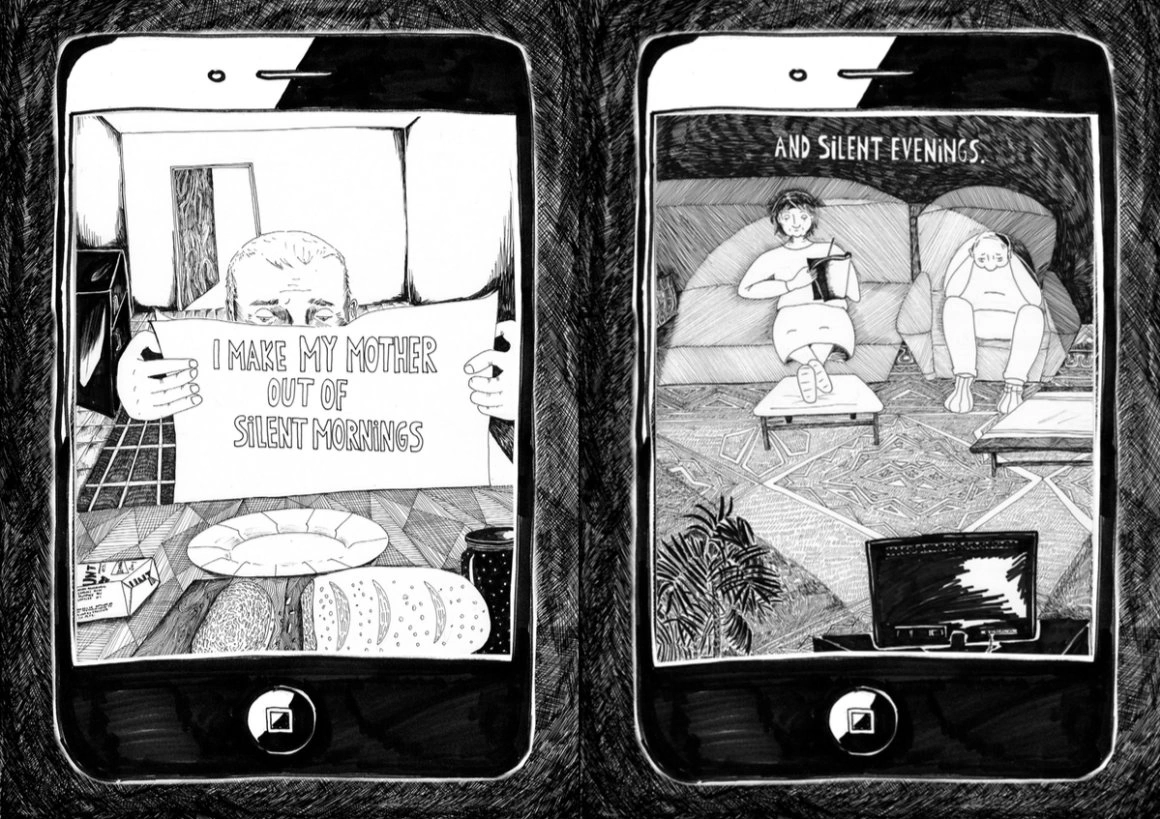

Andreea ponders quite a bit before she answers, and in general it appears that she does a lot of thinking. She’s got the elegance of people who don’t just throw words around. We leaf through the book and I ask her why she drew the discussion with her mother inside the screen of a phone. “It starts with calling someone, it starts like this for a lot of us, and it stays inside the phone. There are a lot of details of this kind, which you only see if you take a second look.” She’s right. The feeling that you’re losing control of the things that are happening to you, along with feeling captive inside a space and inside a time where you’d rather not be (the way breakup can hold you down), all these move from one drawing to another, without the need of words.

“And there’s a lot of silence in the book, I actually tried to add as little text as I could. I’m not a professional comic strip cartoonist, I did it exactly the way I felt like doing it. I just felt that it looked good, that it is the way it should be. If I had been working in advertising, as an art director, I would have probably done 7,000 variations on a drawing and chose just one. This job kills you, it cripples you, and it formats you.” She talks from her past copywriting experience. It’s easier to play with images, than it is with words. “In advertising, you cannot express yourself. It’s very hard to add something. When I draw, I can add a cat behind a chair. And you can’t see it, because it’s small, but I’m so happy about it. It’s my addition, the client will not say that this cat is not in their brand guidelines.”

We’ve almost finished our bottle of wine, but I’m still not clear about two things. Why is she writing in English? Firstly, because this way, the book can reach more people. Like a a Paris bookstore. Secondly, because “I might be afraid to take on the role of a writer. And the English language keeps me at a distance. I’m expressing myself in a rudimentary way, I’m not making a big spectacle out of things. I think I’m afraid. I’m not afraid to draw badly. But I’ve been told no so many times as a copywriter, that I’m afraid of making a mistake.” Why so much black and white? She said that she might be seeing the world in black and white. Or maybe it’s not yet time for color.

The same way it wasn’t time for social issues. “Somebody asked me You’ve got a very sharp way of stating things in just one sentence, why don’t you change directions to a more social area? At this moment, I’ve still got plenty of personal areas I need to go to. And I need to explore this as much as I can. For example, I’m very uncomfortable drawing myself naked. I hate doing it. But I have to, it’s up there with all those other things. I simply shy away from other things. Because of this type of exposure, because it’s not a pseudonym, but it’s my name out there, it’s me.” Out there means Instagram, where Andreea uploads a cartoon a day, on her natural person [Romanian: persoană fizică] account.

I envy her work discipline. And because she’s pushing forward with the exploration of her identity, in a cultural space where exploration is sometimes synonym with exhibitionism. “I think it’s important to see how far I can take this. That’s what I thought, that if I wanted to be a real artist, I must go as far as I can, because that’s the only way you can stop from becoming a cliché. And besides, it’s clear that I can never do cute, nor be cute. But who knows, maybe one day I might start doing cats all over the place.”

From the moment we met, I check her Instagram account daily. I don’t know how she does it, but I find pieces of myself in her drawings. “I really want to post a drawing a day, for a whole year. No matter what I need to do on that day. Ideas come to me, some I jot them down in my phone. Actually, thoughts come to me, phrases, and then I draw them. For me, it’s a good exercise… to learn to expose myself, to become increasingly braver. I want to learn how to do that. These thoughts, fears, these things that aren’t that cool, that are lame, these tedious things… If I want to do this, and I really do want it, it’s important for this process to become more and more authentic. And if for me, authentic means to talk about personal things. This is what I will do.”

I tell her that as I was reading Home Alone, I remembered about the time I lived alone in an apartment on Veronica Micle street. Whenever I would come home and see Matilda, I had the feeling that that cat was the only person in the world who understood me. There’s a cat in Home Alone, too. But it’s not Andreea’s cat, it’s the apartment building’s cat. In the meantime, she got one for herself and her name is Steluța. “From the moment I got a cat, I became obsessed. And you’re right, sometimes, when I come home, I’m so happy to see her and I think she’s also very happy to see me. But you never know…”

You can find Home Alone in Cărturești, at the Salonul European de Bandă Desenată (European Comics Salon) (9-22 mai, Scena9 Residency, at the Jumătatea Plină bookstore stand), in the Volume bookstore in Paris and on Decât o revistă’s website.

Andreea Chirică also illustrated Răzvan Exarhu’s first book, Fericirea e un ac de siguranță (Happiness is a Safety Pin), coming soon at Curtea Veche Publishing House.

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea.

For more fresh English-language cultural journalism, brought to you by the new voices of Romania, look here.