Muzeu3017 is a 2017 exhibition about the types of housing that exist in present-day Bucharest. It illustrates the findings of an anthropological research published last year by Vira Association and the Bucharest Housing Stories project. The organizers placed the exhibit in a completely different and utopic world, 1,000 years into the future. In world that lost the connection to its past after a great digital earthquake. A world that no longer knows about how people used to live in 2017. They did this to hint at the detached and alien perspective that anthropologists use to observe a society. Another reason was to cement the information about the present and recent past in the minds of people. What resulted was a friendly and interactive museum that invited its visitors to reflect critically on things. I visited the exhibition as a journalist from the future.

***

Dear readers, did you know that 1,000 years ago Romania had the highest home ownership rate in Europe and was also one of the world’s leaders in vacant residences? Did you know that some people were evicted from their own homes and would end up sleeping on the street? How many of know know now, that 997 years ago, the leader of the United States, Donald Trump, was lynched by penguins – a species that is now extinct? Or that 999 years ago, the subway, an archaic means of transportation, finally came to Drumul Taberei, a neighborhood in Bucharest, Romania’s capital. Does anybody even know what to inhabit means anymore?

Last year, in 3016, we found the answer to this last question. 40 years after the Great Digital Earthquake that shattered almost all of the data found on the Internet and our relationship with the past, researchers have discovered a treasure that is 1,000 years old: facts about how our Bucharest ancestors used to live. The data was collected by the practitioners of a lost science: anthropology, which used to analyze the socio-cultural differences between people. Yes, there used to be differences between people, back in those times. They’ve recovered stories, images, objects, and sounds that have miraculously survived the Great Earthquake and they’ve released it to the general public. Recently, all the findings have been displayed in a museum exhibition that illustrates seven different housing types in 2017 Bucharest. I toured the exhibition and it troubled my circuits.

inhabitation, human-space relation based on the exclusive and continuous occupation of a space, and the continuous adjustment of that space to the person, and of the person to the space [related terms: place, dwelling, inhabitant, to live, uninhabited, replaced]

At one point, I woke up in an uncomfortable position. I had my head inside a black box suspended from the ceiling, and the rest of my body was outside, in plain sight. The space was tight, I could hear a strange sound, and the air was stuffy. Whenever I would look up, the lights were moving as to appear that above me, there was a universe that I didn’t have access to. For a moment, I entered the world of homeless people. In 21st century Bucharest, there was a type housing that is very hard to envision in our times: the street. It was not a choice, but the effect of individual circumstances and unfortunate socio-economical contexts. Similar to me inside the box, the homeless people were both visible and invisible: everyone saw them, few noticed them, and many despised them. Their presence on the streets seemed to reinforce in the people of Bucharest one of the time’s biggest fears: that anyone, at anytime could end up on the street.

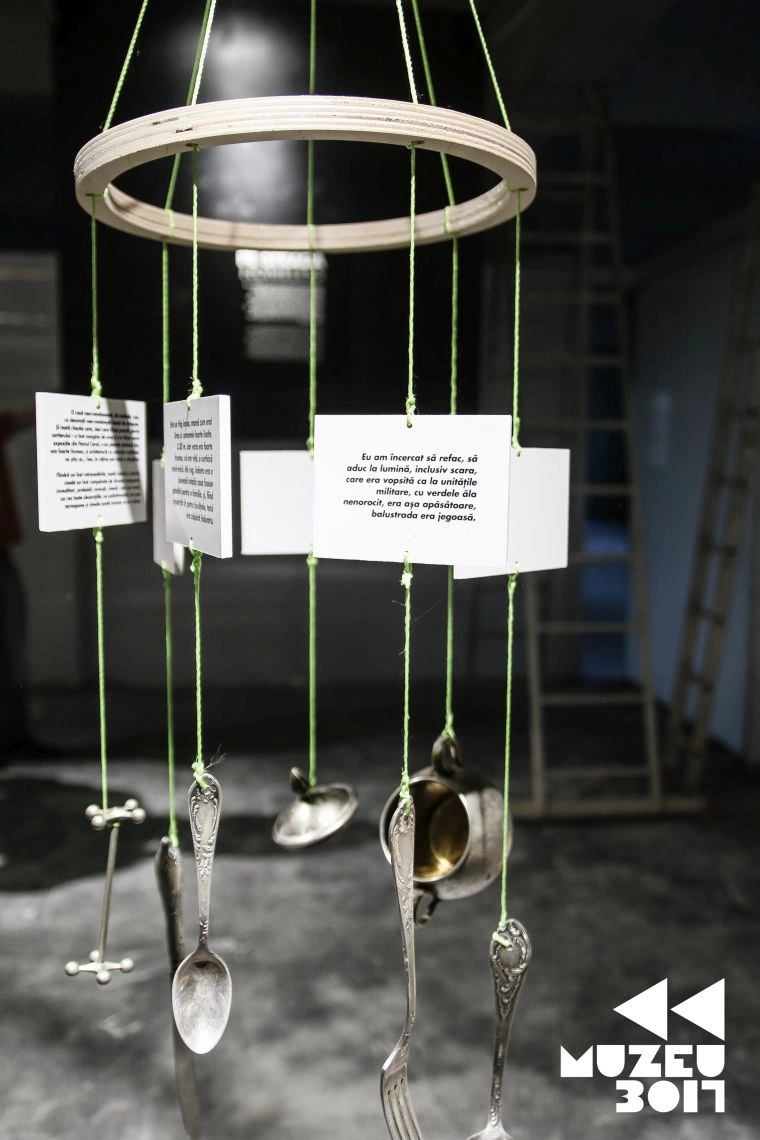

Many of the homeless people had known other types of housing: such as nationalized houses or apartment buildings. The first type had quite a rocky history: the houses were confiscated by the time’s government from privileged people, who were then moved into apartment buildings, or forced to share their homes with other families. The houses were then given back to their initial owners, by another government. All this led to some of the occupants being evacuated right into the street. The exhibition illustrates the fragility of this type of housing, by joining together some of the time’s objects, such as a hammer and a glass figurine. Or, through the use of a large red dot which signaled a grade 1 seismic hazard building. The occupants’ confessions are written on archaic objects – forks, spoons, pots, or on a rotating installation.

It was the time when several families would share a home. Sometimes, in a large apartment, there would live two, even three families. In other more unfortunate places, I heard of cases of families that were divided by a single piece of sheet.

We lived our whole lives with this fear: that we would be kicked out of our homes.

Testimony from residents of nationalized houses, present in the exhibition

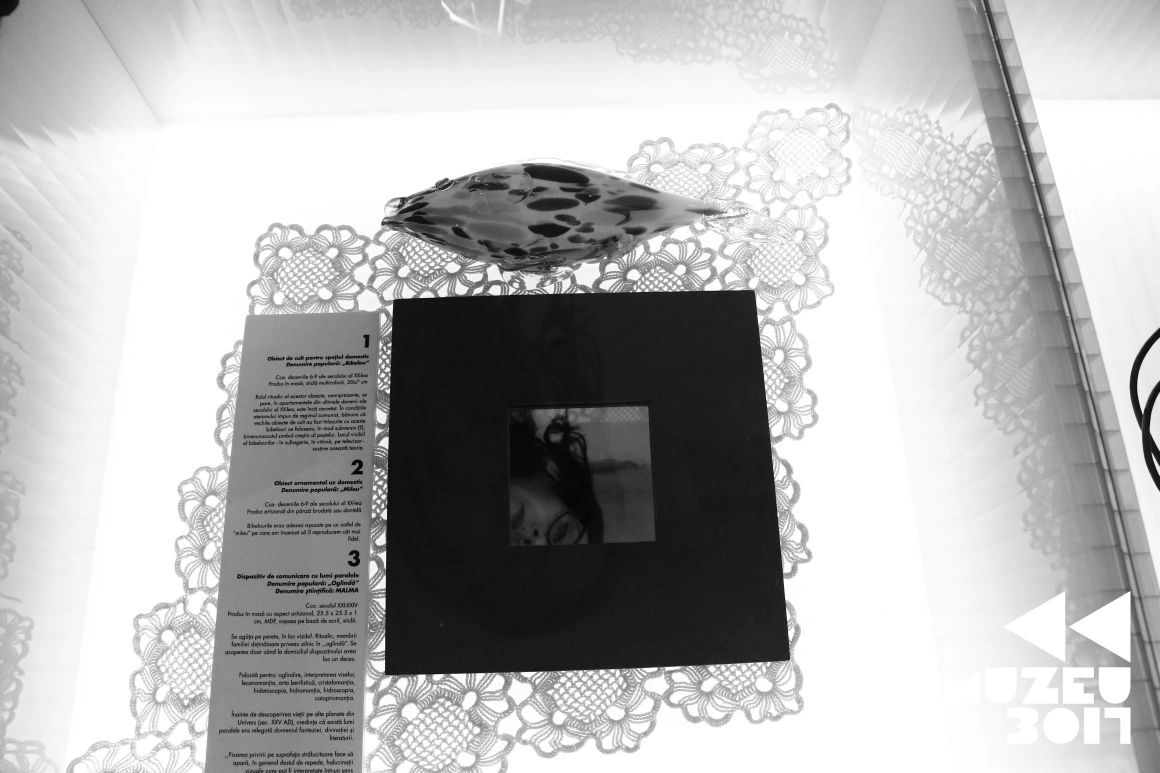

One thousand years ago, the apartment building was the ultimate type of housing. Actually, it was its subdivision, the apartment, a micro-ensemble of spaces, each with different functions, measured in square meters and filled with various objects. The center of it all was the television – I’ll let you discover it yourselves. The others were the mirror, “a communication device between parallel worlds”, or the ceramic figurine – a cult object for domestic spaces, that dates back to the 6th to 9th decade of the 20th century. This is what the organizers had to say about these objects:

The ritualistic purpose of these omnipresent objects inside apartments during the last decades of the 20th century is still being researched. Communism imposed atheism (editor’s note: - an atheism that preceded the capitalist one in the period of time that was analyzed), and we suspect that the old cult objects were simply replaced by these ceramic figurines. Most would subversively use the known symbol for Christianity, the fish. The visible place where the objects would be located – in the living room, in a glass display case, on the television – supports this theory.

In “communism”, there was a massive spike in the construction of apartment buildings. Getting an apartment translated to improvement and social success. But in 2017, living in an apartment building was already considered quaint, crowded, and “communist” (a pejorative term). Some would consider this option a mere transitional phase, while they were waiting to move to a “house on land”, away from the concrete jungle, from the bustle and hustle of the city.

And this brings us to the fourth type of housing, the one that cherished “the house on land”: the peri-urban area. We all know that 800 years ago, the terms “urban” and “rural” became extinct from the intergalactic archival nomenclature. Before this, Romania was strongly polarized between those living in the city and those living in the countryside. There were hybrid areas between the two, which were called peri-urban. They were a type border living – borders were a phenomenon that were specific to the 21st century, when mankind was still obsessed with boundaries.

People who lived in a peri-urban area, were living both in the city and in the countryside. And they considered this ambivalent living as advantageous to them: they had their nature and were living in a “house on land”, and they had the possibility to hold a job in the city, and yet have close ties to their neighbors. Being close to the highway and the main access routes was a thing they used to pride themselves on, at times disturbed by the phonic pollution produced by the traffic and the occasional wind gusts. The exhibition illustrated this type of housing through a few white boxes, ornate with dirt and wild vegetation and covered in maps, pictures, and testimonies from people. Here is a sample from Ms. Jeni in Chitila:

A special place in this setting was held by the student dorm. It was a type of housing that was “intermediate” and communal, meant for young people who, at the end of the third millennial, were still forced to move to other cities to finish their education and couldn’t financially afford another type of housing. The student dorm was in itself a form of education for young adults, a passing rite, a means to learn, socialize, and mature. The exhibition symbolizes this space through a rectangular box where food was stored, called a refrigerator, a highly prized assent inside a dorm room. There are surprises waiting for you inside, if you dare open it.

In the first year, I put in the floors in this room. In the second year, we put in the floors in the hallway. And that’s how we created our own comfort. We bring our own fridges, our own cooktops.

If you’re lucky enough, you’ll find a cockroach or two, from time to time.

In the bathrooms, there’s definitely a lack of hygiene. But the whole idea is to stand united. We meet up in the hallways, we go out.

Testimonies from young people who lived in a dorm, glued on “jars” in the exhibition

The two other types of housing displayed in the exhibition have something in common: the flagrant idea of border, of delimitation, but from completely different perspectives. In one corner, we have the residential complexes (or gated communities). In the other, we have the ghettos. The first ones inspire order and luxury, and were used to house the people who were willingly isolating themselves from the others, inside areas with restricted and controlled access. This gave them the sense of security and a privileged status. This is evoked in the exhibition through a barrier, a surveillance camera, and testimonies from the occupants, under the slogans “new”, “clean”, and “safe”:

For a few days, we slept in an empty room, on our mattress and we used to eat on a chair. Slowly, we got everything, but we didn’t want to bring old things in a clean house, that smelled new.

Police has nothing to do with this. The only solution is security guards inside the residential area. The security cameras are good, but they’re best used for criminals, not for garbage scavengers.

Testimonies from occupants of residential complexes, present in the exhibition

Around the corner, we find the exhibition’s most comfortable area. You can lounge on a bean bag (remember those?), or in the shade of some laundry that have a fashion feel to them. But when you hit play to the clip in front of you and you read what’s written on the wall, everything becomes uncomfortable. You realize that you find yourself inside a “poverty bag”, the term used by authorities to call the ghettos – a type of marginal housing, that used to push the poor people to the edge of society. The state had no solution for this type of housing. Social exclusion, degraded buildings, overcrowding. In 2016, Romania was the European country with the highest home ownership rate – 97% of the housing was owned privately. But the country also had the smallest and the most cramped spaces. In the ghetto, whole families could share one room that was up to 10 square meters. Romania was also the country with the largest number of vacant residences in the world.

After a tour of the exhibition, you can’t help but notice two things: the people in the past used to have a strong relationship with the spaces where they lived, a fetish even. In that society, the complete lack of such space would nullify one, as an individual. All these types of housing were the mirror of the social inequalities – problems that we no longer face – and of the political ideologies that came and went. The states and the people themselves felt the need to place borders between individuals. This phenomenon persisted for a long time: even though the state borders disappeared with the Great Abolishment of Borders of 2217, the walls and personal fences continued to exist for at least two more centuries.

Back to the present day, we chatted with the exhibition organizers. Aside from the Vira research, the organizers consulted resources, and reconstructed the history of certain housing types, as they gathered objects to justly illustrate them: ceramic figurines, doilies, garden hoses, telephones, flip flops, can openers, etc. Daily trivial objects that are presented differently. They come with the labels that one would usually find in a traditional museum, but some of them, though plausible, are not real. The can opener, for example, is described as a “non-magnetic card”, used as punch cards, by the students who needed to work through college.

“Our exhibition is a critique to museums in general, to the way in which education is done in museums, and to the relationship between an exhibition and its visitors”, says Simina Bădică, the curator of the exhibition. The organizers aimed to attack the authoritarian and pedagogical tone used by traditional museums. The submissive attitude that the visitors are introduced to since first day they step foot inside a museum, usually brought there by the school. They also wanted to encourage them to be more critical, because what they’re seeing in a conventional museum, isn’t actually the truth, but a filtering of the information. “[The visitors] do not question what they’re getting, and the content from the museum is most often than not an interpretation done by the museologists. They are all types of suppositions, things they choose not to say, especially when it comes to controversial topics. Our labels closely imitate this type of museum labels.”

The objects we chose don’t necessarily represent the type of housing they accompany. “Not in the classical sense, anyway. They don’t say: this is what living here means”, says Iris Șerban, another curator. “They try to say something, to shock. Think of the ceramic figurine and the hammer from the nationalized homes. Why? Because they are a fragile type of housing, because of all their history”. On the other hand, they are “social objects”, meant to bring people together, to make them discuss their past and the social issues of the present.

The exhibition also has an educative side to it. It’s meant to raise awareness to the subject, in a detached and non-aggressive manner. “We tried to choose the most important aspects, both positive and negative, of living in these types of housing”, says Vlad Stoica, an architect with Wolfhouse Production, the exhibition’s third curator. “But inhabitation is very much politically charged. It’s a type of control, it betrays certain ideologies that are practiced by governments at various times in history. You simply can’t move away from this when you’re trying to look at any of them objectively. With every single installation we did, we simply wanted to impart a feeling, not to illustrate an idea exhaustively”.

For example, for the homelessness installation, we wanted to just create an unpleasant feeling, that would put the visitor in a vulnerable situation: you have your head inside one space and your body in another. “The same way that homeless people are”, says Simina Bădică. “They are quite visible to the world, and at the same time, they’re invisible”. For the peri-urban, they wanted repetitive structures, because this is what this type of housing suggests. “It’s pretty repetitive. You don’t really see anything else, but houses and, from time to time, a store”, says Vlad Stoica. “We really wanted to have an olfactory element to this installation, that’s why we brought plants and dirt. Many people were talking about the idea of having a garden, a house on land.”

For the residential complexes and the ghetto, we used the idea of contrast and borders. “Safety is very important and very much mentioned by those who want to live inside a residential complex”, mentioned Simina Bădică. “This is why we have a barrier in our installation, and the fact that the residential complex is near the ghetto also isn’t a coincidence. We tried to make our visitors pay more attention to the idea of border and fence. In reality, the two are not bordered. I thought it was interesting, this play on borders and fences and how they both protect and separate you from the others. For those inside the residential complexes, a fence means security, for those inside ghettos, it represents their inability to leave their condition”.

The theme of the exhibition was Dragoş Neamu’s idea. He works with the National Museum Network of Romania, the organization that coordinates the Night of Museums. He wanted to create an innovative prototype of a museum in Bucharest. The exhibition can be visited until July 19, along the river Dâmbovița, inside the Cotton Industry (Industria Bumbacului). This is where Nod Makerspace, the producers of the exhibition, are also located.

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea

For more fresh English-language cultural journalism, brought to you by the new voices of Romania, look here.