Today, you can see the silhouette of the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant (Muzeul Țăranului Român or MȚR) from behind the scaffolding and canvases, as if it were an anesthetized body set for surgery. On its walls, you can also see the clean sketches, the sharp and unequal letters of the institution’s first director, artist Horia Bernea. In one of the black and white photos, Bernea is sculpting a mannequin head. Right next to it, he’s giving instructions on how to arrange a gallery room. For those who love MȚR, these images seem to act as a promise that the “barricade spirit” of the institution shall resist.

In the first few weeks of democracy, the idea of a museum that would bring back the ethnographic legacy of Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș in the Kiseleff building, to replace the Communist Party History Museum, seemed like such a natural gesture of reappropriation. But what Horia Bernea, cultural anthropologist Irina Nicolau and their team would do in the following years was so much more than reappropriation: they would peel away the clichés of the peasant and would show the city people the richness of the rural world, in all its simplicity and vulnerability. Instead of labels and display cases, the museum invited the visitor to seek and find the meanings of an object on their own. From time to time, the museum would take to the streets and look to create a connection, through taste, hearing and playfulness, with the people who had never had these types of experiences. It wasn’t always comfortable, but it felt alive and it was useful.

In 1996, MȚR was presented with the European Museum of the Year Award, a feat that hasn’t been achieved by any other Romanian institution since. “The jury’s opinion is that this museum has reached the highest level of esthetic presentation and has an unparalleled imaginative quality”, said the motivation behind the award. Even after Horia Bernea passed away in 2000, and Irina Nicolau, one and a half years later; even after scandals, resettlements and changes, the spirit of the museum continues to thrive there. This is what cultural anthropologist Ioana Popescu believes, who was part of the museum’s team from its conception and curated the its Image Archive. She thought retirement would keep her away from MȚR, but she keeps coming back. There’s just so much to do.

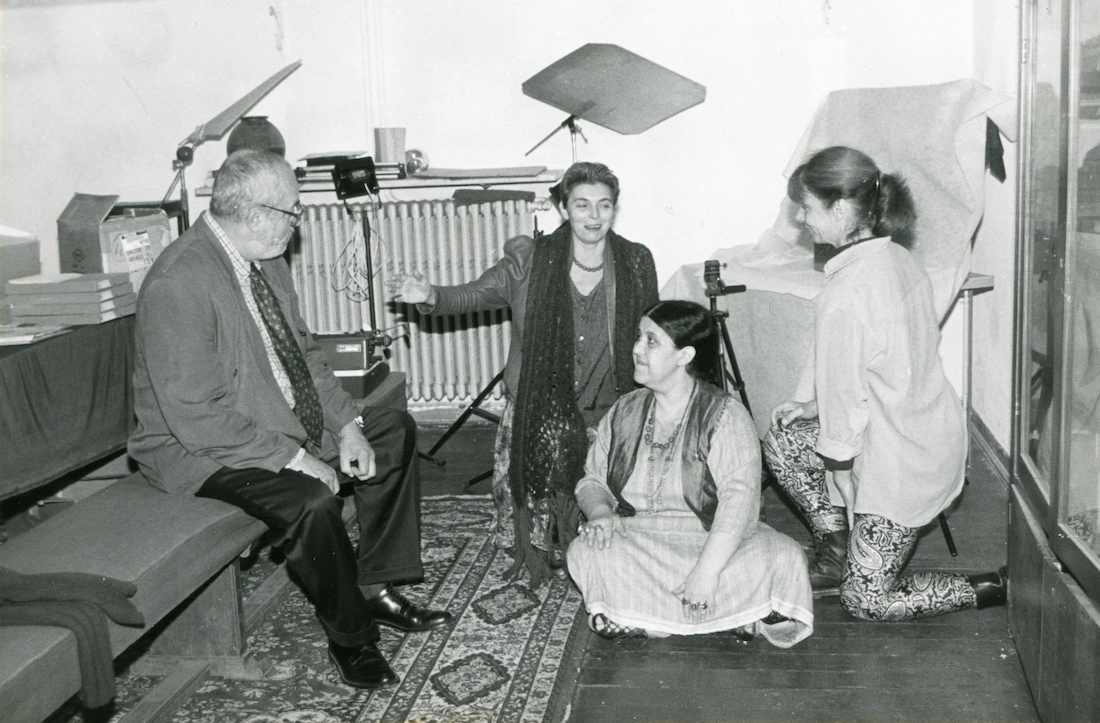

I talked to Ioana Popescu about what it means to “eat clouds” at the museum, about her work, about the boldness, conflicts, fragility, and playfulness that keep that place alive. Then, I set her words in dialogue with those written by Irina Nicolau and Carmen Huluță in “Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”), as a type of fragmentary diary of the first years of MȚR, along with photographs from the museum’s Image Archive.

Scena9: The Revolution caught you recording.

Ioana Popescu: Of course it did. It was Irina’s idea to write things down. She spent all her time indoors and would record everything that was happening on the TV, because the Revolution was broadcast live. And we were in the streets, each of us trying to do something to change things. And she said: “When you get home, write everything down!” There were just a few of us, all friends. Eventually, thanks to Irina’s gentle nudges, we all worked together and this book came out [“We Will Die and We Will Be Free (The First Book on the Revolution)” („Vom muri și vom fi liberi (prima carte despre Revoluție)”, an anthology curated by Irina Nicolau – editor’s note]. We had the most beautiful times working on the book itself, because it had initially been published as a samizdat, a handmade book. There was this machine that would print page by page, we’d found it in the cellar of the Museum. Because it was old, it put out these wonderful pages, unequal, with faded writing. It was something truly spectacular. Then we got all the pages together, from 1 to 200, or something like that and we would run after each other like ants, getting them all together and stapling them. It was a great team work, done at night, and we truly felt as if we were all one entity.

„End of December, 1989. (...) At the Institute, everybody’s gone mad. We don’t care, we’re working on the book. I record during the day, I transcribe at night, and in the morning, I delete everything, so I can record again. I’ve got a total of eight tapes. Speranța [Rădulescu] and Ioana [Popescu] are also working on this. People only talk about the terrorists. There are roadblocks on the street. Ceaușescu was shot, but some say that he didn’t die. ”- Irina Nicolau in „Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”) (Irina Nicolau & Carmen Huluță, 2001)

People were drawn to what would eventually become the Museum of the Romanian Peasant because they wanted to “eat clouds”. It’s an expression I found in Irina Nicolau’s “Sentimental File”. I found it again with the generation that is now curating the Museum’s Image Archive.

There are so many of Irina’s aphorisms, passed down through me or others.

What does it mean to eat clouds?

To go beyond your worldly condition and create extraordinary things. It’s actually a saying that we used a lot in my family. I suppose it was something that the post war generation said.

February 3rd, 1990. We started making a list with names for the new museum. How should we call it? What’s the right name? (...) We write down everything we can think of. God, why didn’t I keep that piece of paper?! I know for sure that Horia wrote down numbers in front of the names and we had around 20 of them. He came up with the Museum of the Romanian Peasant, but he didn’t like it. A few hours later, we picked that exact name, the one that annoyed so many people during the first years. Peasant? It’s pejorative, the French said. Romanian? It’s limited and politically incorrect, others thought. Later, we regretted that we didn’t just call it the Museum of the Peasant. The Dimitrie Gusti National Village Museum and the Museum of the Romanian Peasant– we wanted a bus to go between the two every hour. ”- Irina Nicolau in „Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”) (Irina Nicolau & Carmen Huluță, 2001)

I thought it really captured what the Museum aimed to do.

That’s how Irina “lured us in”, because we didn’t really want to leave that cozy spot of ours [The Institute of Ethnography and Folklore – editor’s note]. I had graduated from the Faculty of Art History, I was doing my internship at the museum and those were some of my unhappiest days. For me, working in a museum was something terrible, I didn’t want to be a paper-pusher. I didn’t want to come to the museum, in the first place. Irina lured us in with the statement that “this museum shall be a barricade”. The Revolution was barely over and she was telling us that we would make a cultural barricade out of this museum. That’s how it got started and that’s how we tried to mold this place – Horia Bernea, Irina Nicolau and the rest of the team. The museum’s agenda was a barricade one, and so was its discourse. It was a once in a lifetime chance.

So, it kept some of the Revolution’s spirit.

Yes, it did. It completely redefined museology. It took chances and assumed all the risks and the reactions that would potentially come from conventional museology: “the art will get ruined”, “the art objects are not in cases”, “people will come and then leave without learning a thing, because there are no descriptions”, and so on and so forth. The museologists were used to fragile objects, and sometimes you can’t break a pattern. Treating everything like “Egyptian artefacts”, trying to get them to stay in the same shape and form as when they were acquired. But we felt that these objects were little bits of life, taken from context, of course, but still objects that can be recontextualized in new shapes; objects that can communicate new things, little tiny living organisms. This was very difficult to put into words, because there were two teams with very different views, working on the same project. It was challenging.

„It’s very difficult to create a museum without labels, after a century when the visitor was used to receive the information included in the ticket price. Now you come and tell them: imagine that you’re in a little forest clearing! Take a deep breath and look around you with joy! And in that clearing, you’re no longer concerned with the Latin word for squirrel, you just say there’s a squirrel! The objects in our museum belong to the traditional world. What do you know about it? Dig deep and try to understand! You surely know plenty of things.”- Irina Nicolau in „Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”) (Irina Nicolau & Carmen Huluță, 2001)

Did this tension linger during the following years?

The tension was always there. In a sense, it’s still there today. (…) The difference in vision is permanent. But our case was not unique; the first visit abroad after the Revolution was in France, for an internship at the Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaires. The employers there were going trough the same things as we were: the research laboratory and the museologists were in a constant war of ideas and they were doing endless negotiations to be able to advance the museum. So, we weren’t the only ones. But we were quite special, because there was no other Romanian museum that had a research center. The research used to be performed and still is by museologists, and it’s strictly linked to the object and its form, to the technique and so on and so forth, while the context was never researched. So, our research lab was something utterly new and it shocked plenty of people.

Another issue was that people would quite often leave the museum: they would get a scholarship abroad and they would never return. How was it to try to put something together in these circumstances?

Actually, if we think about it, the core of the museum, the people who created it, is unchanged. But, because the museum itself was a fascinating project, with great potential, because Horia Bernea was an amazing character and many young people wanted to work beside him at least for a little while, because Irina Nicolau was so charismatic that the young folks would be drawn to her like moths to a flame, because of all this, young people would always come to the museum. And they were smart, creative, yearning for change and “eating clouds”. But it was the very same young people who would eventually go on a different path, because they didn’t quite know yet what they wanted from life. They were coming and going. Some of them got their PhDs, and stayed abroad, but kept their connections to the museum, and are still helping whenever they can. Some left and returned to Romania, but not to the museum. It was to be expected, in a way. It’s only natural that this happens.

And this very fragility seems to be a part of the museum’s spirit.

Yes, this too. Eventually, it was established that once every six months, the objects in the museum would be switched with similar ones. So, the installation would remain standing, but the pieces would get changed, so that they wouldn’t get tired. That happened up to a point, when some pieces proved that they were much more appropriate for a particular spot, because they had much more to say than their storage equivalent, so they remained in place. Same thing with the people: they were all very useful at a given time, each in their own way, but then the museum moved forward and they found their own path. This is what the museum wanted, both with its pieces and its people. There was no contradiction.

After you started working on this project, when did you feel Horia Bernea’s ideas were starting to shape up?

I personally got a feel of this quite late in the life of the museum. (She laughs) Irina worked a lot with Horia, they used to talk all the time. She did the talking and the ideas would come pouring out of her, she just couldn’t contain them all. And if you made a face – because this was my go-to reaction, whenever she came up with an idea that surprised me: “No, this is too much” – she would say: “Oh, you don’t like this. Here’s another one!” She was always like that. Bernea used to also make faces, like myself, and at first he was somewhat reserved about whatever Irina would say. She was coming up with ideas, as she was speaking and Bernea would write stuff down or he didn’t and then he would deliberate. Irina didn’t really understand everything that was happening. At first, we would get excited, came up with all sorts of plans, and then everything would stop dead in its tracks. Even Bernea used to sit in his office, and scribble things down on pieces of paper, draw things, get advice from friends, artists, theologians, and priests who would come to visit. He would talk to everybody. He was quite productive in his office. But we didn’t really know if he was actually getting something done, or just trying to place the museum somewhere in his own world and was doing a type of impromptu PR meeting. He was just thinking, deliberating, gestating and then, just like that, he knew. He would call us in his office and from then on, things were starting to make sense. Afterwards, we would all try to apply this in our own rooms, and put our own personalities in the work. But once he sorted things out, it felt as if the discourse had been there since ever: it was coherent and collected. I have no idea what his system of thought was, Irina was much closer to him. But that’s pretty much how things used to go down.

“Beginning of may, 1990. Horia brings another piece of paper to us. On it, there are some drawings, with numbers from one to five. Here, he says, you can organize the museum in five ways. I tell him that I don’t understand, but that I will try to. The only thing that is clear to me is that Horia has a very unique way of seeing and thinking up things for the museum. Very different from mine, at least. During those ten years, I learned that whenever him and I had different views of things, he was usually right, not myself.”- Irina Nicolau in „Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”) (Irina Nicolau & Carmen Huluță, 2001)

From what I know, the work to fix up the museum’s rooms was done by the museum employees themselves.

Yes, we did it all. And it felt as good as it did when we all worked together as a team on the book. Until then, we’d only done research, some typing and we would provide a required number of pages a semester. And now we had the opportunity to dive right in and experiment with paints, put nails in the walls, cut and hit ourselves, carry stuff and have ideas. We would try a certain color and if it didn’t feel right, we would try something else. Up until then, we were passive, and now we were doing things. This gave us an immense joy. And it was quite a competition: everybody wanted to do those things, everybody was carrying buckets and mixing paints. Bernea used to show us from time to time how to do things, and we felt so damn lucky for that!

Go on a virtual tour of the Museum of the Romanian Peasant HERE. The museum is currently being consolidated and restored.

There were so many ideas of events, things that were happening outside the museum, some of them before the museum had even opened its doors. I read about the 300-year anniversary of the first mention of Calea Victoriei that was organized by the museum, when you made a cake with 300 candles.

This was Irina’s idea. I said: “Where would we find a cake with 300 candles?” And she replied: “Don’t you make cake for your birthday?” “Well, I do, but this has to be one massive cake!”. “Then, just do big one…” “But it won’t fit in my oven, it’s a small stove oven. And where would we put it? How will we transport it?” “I don’t know; you figure it out. Make it in sections and then we’ll assembly it on a platform.” And that’s what we did. We made it from smaller sections, one night and put it on a platform to transport it with those 300 of candles in it. We had a giant cake with candles, and we would stop people on the street and offer them cake. They wanted to learn about why we did that and who we were celebrating. This managed to pluck the jaded passerby from their boredom, it made them to open their eyes and get involved. It was something completely novel.

The first time we went out on the streets was with the Christmas Note. This was completely unexpected, because we went out with a horse carriage and a very unfortunate horse brought there from around. We had these exceptional carolers from Slobozia, that our ethnomusicologists lead by Speranța Rădulescu discovered. The way they sang the carols was very unusual, they had this very low tone, as if they were old men singing. The tune was very slow, heavy on the drums and the buhai. For a Bucharestian, this was by no means a carol. A colleague of ours, Gabriel Hanganu had the whole carriage filled with these notes that we had hand made. They were rolled and tied up with strings, and we would hand them to people in the streets. Behind us were these men singing sad songs, and beating their drums and then, there were us, the museum people, feeling embarrassed because it was our first time in the streets. Because we were embarrassed, we were sitting very close to each other, so the people who passed us were convinced that it was a funeral: the cars were honking their horns, they would turn on their lights and we were just slowly advancing our “funeral”. When we eventually realized what was happening, we started making jokes, laughing and things changed.

“1992, winter. (...) Although a tad exasperated, Horia joined us in all those «silly» things we invented. Once in a while we stopped in our tracks. People would join us and start dancing.” Irina Nicolau in „Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”) (Irina Nicolau & Carmen Huluță, 2001)

After that, we kept going in the streets, encouraged by Irina. This whole thing culminated with “The Missionary Museum”. These days, the idea is being reinterpreted, but back then, it really a missionary museum; we really did have to travel to places that a museum and culture, in general, hadn’t been, places that were disenfranchised: nursing homes, children’s hospitals, maternities, and so on and so forth. And this went on for a while. It was quite impressive and you were really feeling that there was something changing in the hearts of the people we were visiting, when we came over carrying a museum in a suitcase.

When you were starting out, there was a street painting competition that was a massive hit.

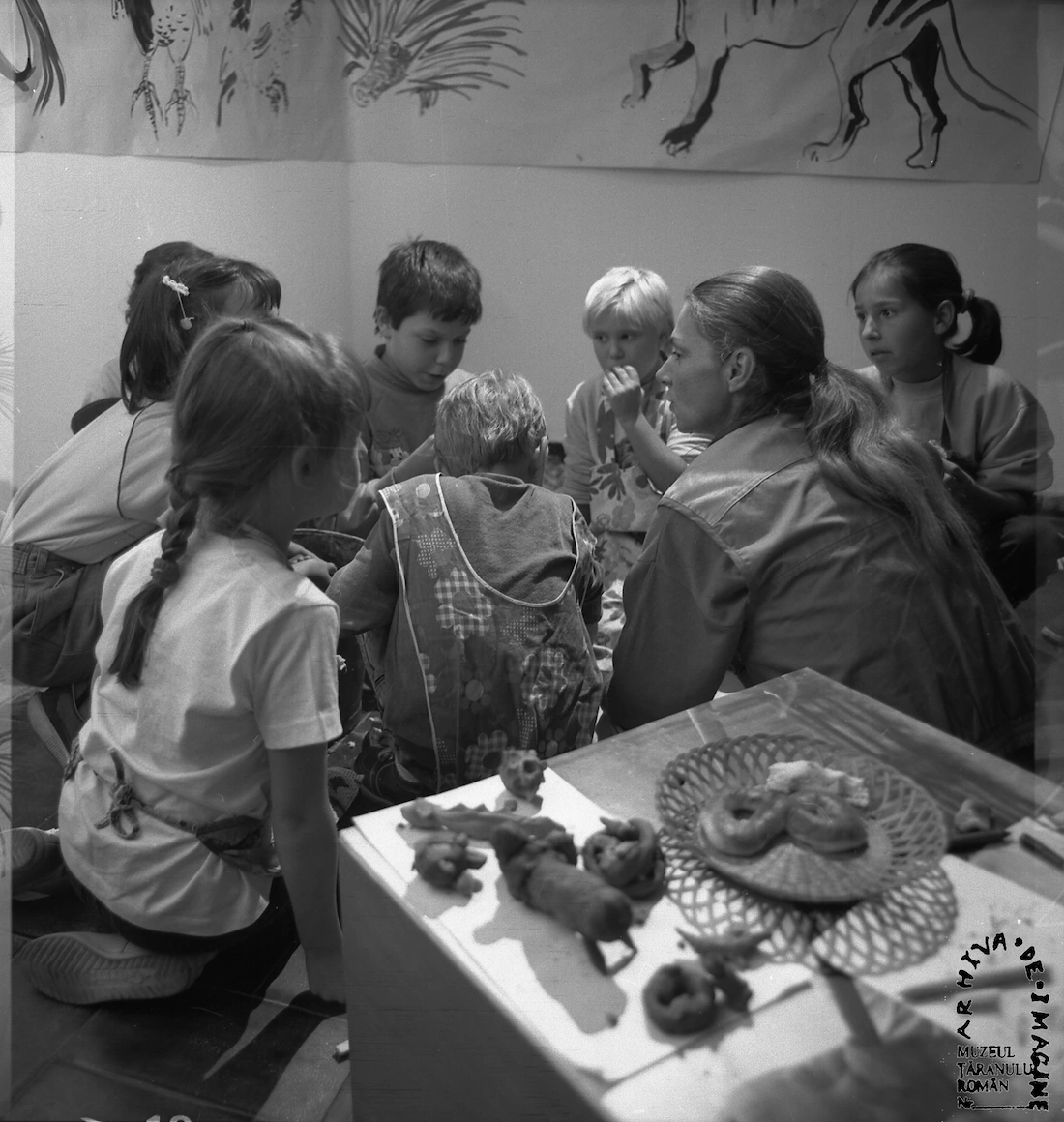

It was right here, in the courtyard. Irina and I wanted to have a part of the museum dedicated to children, it was actually my obsession. We would call it the “Childrenarium” („Copilarium”), because we had no idea how else to call it. We wanted things to happen there: on one side, we wanted exhibits for children, on the other, we wanted the children themselves to take part in the events, and even be the nucleus. The space kept changing to here and there, until there was no longer a place for it. But now there is a Village School, that is aimed at both children and adults. Creativity workshops followed. When there was no space for this “Childrenarium”, I said: “But, why don’t we use the yard?” We’ll just bring the children in to paint the pavement. And we had a massive surprise when a little girl did some amazing paintings. Bernea was in the jury and he was walking among the competitors. When he came to the little girl who did an extraordinary painting, he was just stunned. She won. Later, she was a student of mine at the History of Arts, where she is now an assistant. I found out that she was the niece of a painter, so there was something there that had been passed down to her.

After that, it just stuck. Children worked with us on all of those first actions. For our photography exhibits, children painted the frames. The carpenter built simple wooden frames, and we would call all the children and let them paint them as they pleased. Some did dots, others carved the frames, while others would draw zig-zags. The things that came out of that were incredibly creative and sincere. We used the frames for a long time, until they just couldn’t be rebuilt, because we had taken them apart and put them back together too many times. Working with children can give surprising results.

“June 1st, 2990. (...) It was the museum’s first action, small and unoriginal. But we did it without being formal and we did it with warm-heartedness. We’ll try to make «authenticity» a characteristic of our museum”. - Irina Nicolau in „Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”) (Irina Nicolau & Carmen Huluță, 2001)

The museum was also trying to integrate what appeared to be a type of kitsch in its exhibits.

There are two sides to that. One one side, it was Bernea’s idea to integrate ugly things. It had nothing to do with kitsch, but with what was ugly in the rooms: the hydrant, the metallic cap that covered the electrics, various bits of chipped wood, that he insisted were left as they were. Or even more so, he highlighted them by badly painted them or placed a frame around them to make them more visible. That was one type of endeavor. And the other was Irina’s, who loved kitsch, and she and Horia were a great pair, because of that. She studied it, collected it and treated it as she would precious things. She knew the difference between kitsch and real art, but she loved kitsch the way children love things, she loved it as you would a helpless animal. She would go to Matache market or Obor and would buy these horrible statues: ballerinas, gypsy women, adorable deer. She had a superb Biedermeier glass display case filled with these horrors. She loved them, she would reposition them, use them in installations, in museum meetings. Irina had no qualms to display the kitsch in the museum. The only room she was solely responsible for is now called Windows, and it has an entire display case for religious kitsch. I believe, no other museum dared to do that, especially at that time. Bernea was a practicing Christian with a very open mind and he accepted that case of religious kitsch. Actually, he didn’t just accept it, he considered it a weapon, he believed that with the help of that case, the museum was campaigning for a genuine church.

“1990, 1991, 1992. (...) Are we doing enough? Are we working fast enough? It’s difficult to answer. One thing’s for sure: these are not good times to found anything. In Romania, there is a huge void and if you want to fill it, you need to use your own body. Or maybe it’s better to build a bridge over it with one leg rooted in Samurcaș’s time and the other one, where the future begins. But are we smart enough to build a bridge? And will we work fast enough? That’s the issue.”- Irina Nicolau in „Sentimental File” (“Dosar Sentimental”) (Irina Nicolau & Carmen Huluță, 2001)

Two and a half decades have passed. There have been various issues, including the search for a museum director. Is there something left of the museum’s initial spirit?

The spirit of the place was preserved extraordinarily. And it’s good, but also bad that this happened. What remains is that type of feeling of interconnectedness between objects, of giving exhibits a certain flavor, of always surprising the visitor. What remains still is the idea of leaving the visitor to use their own brain, without serving everything on a platter. There is a lot of Bernea in the graphics of the museum and the publications. There are the relationships between people. This is good, because the museum’s world is still alive. But the effects of these things aren’t always positive: I can vouch that there will never be peace and quiet in that museum. There will always be conflicting opinions, people will fight for their own voices to be heard.

Unfortunately, ever since Bernea left us, so has that authoritarian voice that allowed things to come head to head, the same voice that helped settle things. Anyone who tries to do that, gets a slap in the face, because they don’t have Bernea’s authority. Things will keep moving. I believe that whenever the museum is back on its feet, there will be blood. But I welcome it, as I’m sure something good will come out of it. This clash between “We’ll just do things as we used to” and “We understand how things must be and we’ll make adjustments”, is a very serious conflict. This is what I mean when I say that the spirit of the museum is still alive. The spirit that was brought there by Bernea and Irina. Besides, it’s the way people treat each other, which comes from Irina: it’s a certain way of not just being familiar with one another, but of knowing each other on a deeper level. We know a lot of things about one another, good and bad, about our families, about our plans, about how we got into a fight with our mother-in-law the previous night and we simply can’t make it to the conference, because we’re not feeling like ourselves. There is a way people do their work that has persisted, and I hope that it endures.

What is your relationship with the Museum now? Especially with the Image Archive?

You know, I was thinking about this very thing, as I was coming here, short of breath. I retired thinking that I would finally get to relax and breathe. I’ve been making plans for my retirement for years: I bought an old loom and I learned how to weave; I started learning Greek. Irina was Greek and she used to talk the language and she tried to teach me some here and there. We would chat, but I had my small boys back then, they were all preschoolers, Irina would talk to us, and two days later, I could barely remember the word for mother, and by boys were talking Greek. I wasn’t too happy with this, so I gave up, it was simply unacceptable. And now I can finally learn Greek, because I’m retired. In the meantime, I do a little bit of exercise, so I won’t end up a hunchbacked old woman. What else? Concerts, the opera… I thought that it would be more than enough to fill my time. But actually, the relationship with the museum is far from over: there’s always something going on. A meeting, I get a phone call asking me about what’s best for the museum. I still have some work to do with the Archive, because I have some unfinished business, that I really do need to see through. Meanwhile, some money finally got through for some old projects, and I need to do that. So, my relationship with the museum is more tight knit than I would have wanted it to be, but I’m glad it’s like this. This place is like a home to me, so it’s pretty much like working from home.

“A soothing museum, but one that raises problems? But what does it mean to raise problems? It means to draw attention to the profound meaning of life and death. A museum that raises problems forces the visitor to ask themselves questions about things that generally overwhelm them”- Horia Bernea („A Few Thoughts on Museum, Quantities, Materiality and Crossing”)

Main Photo: D. Dinescu

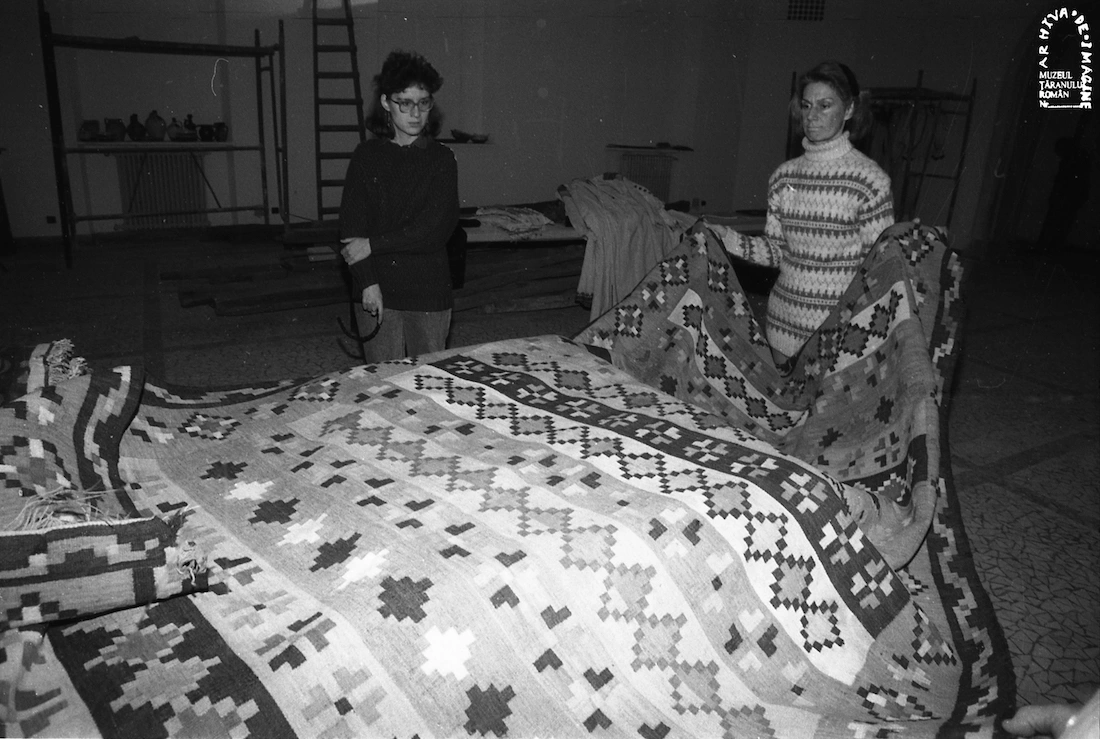

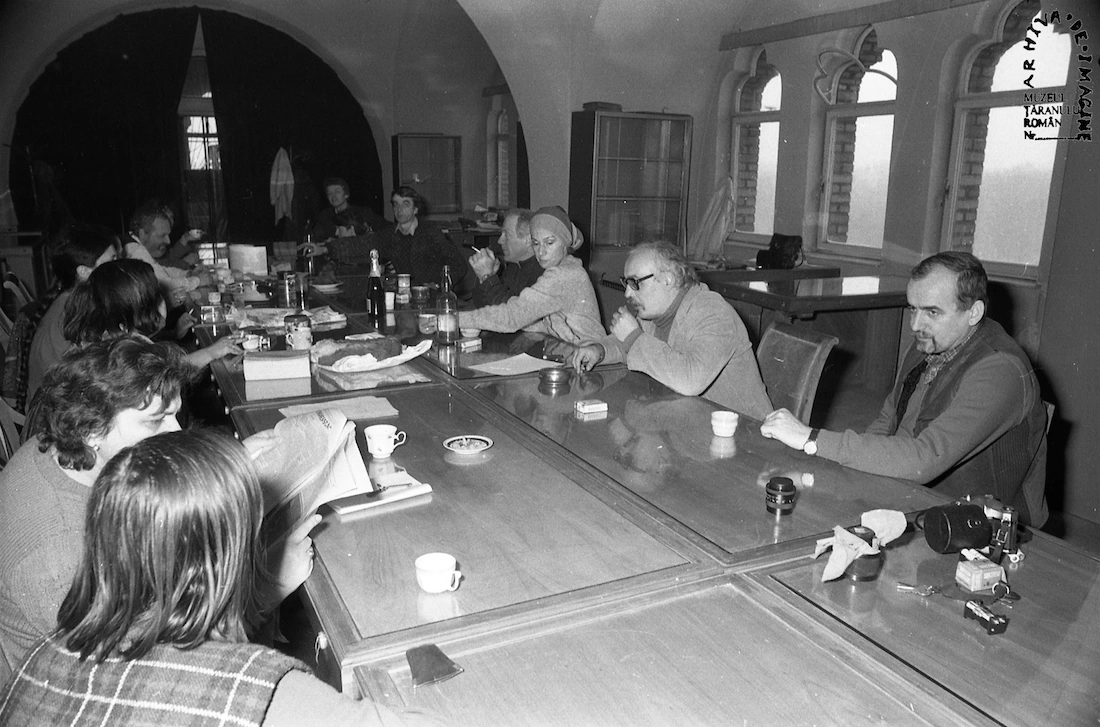

Photographs from the Image archive of the Museum of the National Peasant

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea.