The class structure of Romanian society can be identified through a simple tap on a furniture. Anthropologist Bogdan Iancu learned about this from a respondent during a research interview for The Material Culture of Romanian Middle Class. The interviewee, from the lower middle class, tapped his finger on his Ikea coffee table. It sounded hollow. The sound of the middle class needs to sound deeper, thicker. When you go up a step on the social ladder, you don’t get an Ikea table anymore.

Middle class members aren’t just looking for thickness when it comes to furniture, they want to fill themselves up with qualities, to have time for more than just Excel files, they want to reinvent themselves. A November 2013 Smark Research study revealed that only 13% of the middle class considered job safety important.

It’s hard to take a snapshot of the folks that make up the middle-classers. According to a document provided by the Research Institute for the Quality of Life, their incomes vary a great deal: while some earn good money, others only have “professional and occupational status, education, aspirations and mentalities that belong to the middle class”. This is one of the reasons the press frequently states that “we have no middle class”.

It’s not just about the beliefs that come from outside world. Many of the people from the project “The Material Culture of Romania’s Middle Class” say that they’re not middle class. For some of them, it’s because they set very high standards for themselves, and for others, because they are still reevaluating themselves after an agonizing economic crisis.

I talked to Bogdan Iancu and Monica Stroe, anthropologists, about their team’s “expedition” in search of Romania’s middle class.

“What middle class? That’s nonsense! We don’t have that. We have poor people, people who barely make it through the day, and who are spending money they don’t have, and we have rich people.”

[S., 30 years, IT specialist] – from an interview by Ștefan Lipan

What does the middle class look like?

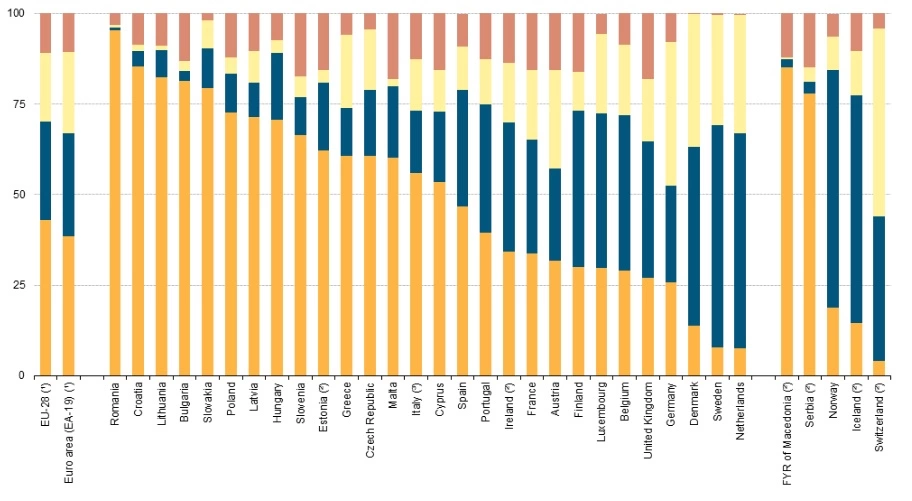

Bogdan Iancu: We are interested to notice how the beliefs about the middle class are translated into real life, how the people talk about this. At first, many of the people we’re conducting the research with are tempted to state that they’re not part of the middle class. For them the questions act as switches. After an interview, they’ll call you: „Well, I’ve been thinking and I think I am part of the middle class”. What we’re really interested in grasping are the ambiguities and the reassessments about the middle class, and not so much as the already-known traits and characteristics. (...) In short, the middle class is an aspirational class, defined not by what it doesn’t have, but by what it might have or become. Many are saying that „in Romania, the middle class was built on loans”. They think it’s a paradox, but this is no paradox. Why do they think that? Because, in terms of housing, Romanians have a tendency to want to have their own home, they resent renting. We have the largest rate of home ownership in Europe. Loans taken for any type of goods are puzzling the sense of ownership, and makes people wonder: “What do I possess?”

Are there any standards that define these people? With no connection to money, though, but with what they want to do, with their concerns.

B.I.: Sociology operates with a few key elements that could condition the idea of a middle class. But our endeavor is merely an ethnographic one. (…) First, we tried to see how people define the middle class. Then, we did focused interviews. We established some demographic data, and aimed for it to be gender balanced. When it comes to age, we focused on the age group between 30 and 40, even 40 something. We did that because that’s where the most active part of the society is.

Do white-collar workers all belong to the middle class, or some distinctions need to be made in that area?

B.I.: It’s true that everybody we talk to sees to believe that there is a connection between the two, it’s as if the middle class was synonymous with white-collar workers. Still, plenty of the white-collar workers we talked to do not perceive themselves as being part of the middle class, because there are a series of conditions they’re still aspiring to and haven’t yet reached; they can’t yet manage their time to their own desires, they have a heavy work load and this makes them feel quite proletarian.

How did this project start?

B.I.: It was Magdalena Crăciun’s idea. She has a doctorate degree from the University College London and had a project about the production and consumption of fake merchandise, a type of roadmap of fake clothes. They would leave from Istanbul, arrive in Europe and were being used in a city in southern Romania. So, a group of us researchers got together, and tried to discover the traits that define the middle class. We approached it from each of our academic backgrounds. I focus on the home and material culture: I’m interested in furniture, gadgets, electronics, home appliances, and pretty much all material expressions that define comfort and give value to the middle class, and the way the middle class assigns value to it. Monica Stroe studies practices that pertain to gastronomy, Alin Savu deals with the forms of child investment, Stefan Lipa studies the manifestations of pity and compassion, and Magda, the project’s manager, studies the practices of clothes consumption. (Editor’s note: You can find details about the team, here)

When did the interviews start?

B.I.: We started in November 2015, with discussions and calibration interviews. It is a research that is largely based on the discussions we do every other week, in order to refine the discoveries made by each one of us. (…) We recently started to focus our attention on how the middle class is expressed in music.

We found a type of anthem: Vama Veche - „Vreau să ajung la radio” (translator’s note: Vama Veche – “I want to make it on the radio”). The song is a clear picture of the middle class’ desire to escape. I’ll give you two examples: firstly, “the free standing house”, which comes from the folklore generated by commercials, and then there’s the fact that the song isn’t about a kid who wants to make it on the radio, but about a guy who wants to escape the rut; about a white collar worker who wants to do a creative job, and about his girlfriend who wants to become an actress. I think we should also do something about the portrayal of the middle class in movies.

The middle class is the area where people earn an honest living. They earn enough money to reach a certain level of comfort that allows that to leave their hamster wheel from time to time, but that’s about it.”

[A.D., 29 years, photographer] – interview by Monica Stroe

Something I noticed from the interview fragments published on your website is that people are saying that “we have no middle class”. Where is this coming from?

B.I.: I think it comes from the high standards they set for themselves. That’s why they make up their minds after the interview. When they analyze their situation by looking back, to their parents and their younger relatives who haven’t managed to get where they are, then they start to position themselves in the middle. If they set high standards for themselves, then they don’t perceive themselves as part of the middle class.

Something else I’ve noticed is that when people say they’re from the middle class, they relate to their own past, never to others.

B.I.: Some of them relate to time, when they’ve had a harsh upbringing and started very low. But there are people who went straight for the winning ticket: their first job was very well-paid and those people never relate to things like that. But for each and every one of them, what is important is that they’ve made an effort to be where they’re at, that they’ve earned it.

Also, there are people who don’t label themselves as middle class, because the economic crisis made people reevaluate their self-perception. When they found themselves not being able to pay off loans, they started to feel shame, as if they were duped by a Ponzi scheme. (…) The crisis completely changed the way they live their life and consume. From this point of view, this particular research of ours is at an advantage, because it doesn’t overlap with an inactive historic moment, but it comes right after a crisis. And this makes our subjects think long and hard about how they came out of the crisis, what they had to do after it ended, what it meant for them and their friends.

They really avoid any discussions about money. Most say that money is of no important, that “money doesn’t define us” and most talk about education. That is why, for those who are now in their 40’s, the acquisition of cultural capital is very important. They apply for master's degrees or sign up for intensive courses, they do dancing, handmade activities, they’re trying to develop some skills to reconnect to a cultural capital they seem to have lost while they were cooped up in their offices. (…) So many of them are focused on the idea of “breaking up with Excel”. There is a fight between Excel as a metaphor, the office that they’re so addicted to and the artisanal jobs, long forgotten or in the course of being forgotten. It’s doing bird-watching in a delta. And then you come right back.

Monica Stroe: The middle class doesn’t define itself by having certain amounts of money, but by the knowledge that they know how to sensibly use that money; that they’re buying nice things, that they’re enjoying their money.

So, “money is of no importance”.

B.I.: It’s not that it doesn’t matter, but it’s not a requirement. They aim for a better position at work, one that will not keep them in the office until 10 in the evening, as it were the case when they were doing internships or a short time after that. They want to be able to leave at four or five in the afternoon, to go on city breaks…

M.S.: To know what they’re working for.

B.I.: Aside from the yearly summer vacation, they want to be able to afford three or four city breaks a year.

M.S.: And it usually is the case that the contrast is made with the upper class, which is reprimanded for throwing money out the window, on things that do not bring joy, but are merely objects devoid of any meaning, ostentatious goods. Our subjects, as part of the middle class, believe that they have a sense of consumer education.

Do these types of ethics come with the middle class? A lot of people seem to want to show the world that they’re the type of folks who want to do things properly.

B.I.: This is a type of post-communist mechanism.

M.S.: It’s a placement inside a civic perspective. Especially when it comes to young people, the middle class thinks of itself as the backbone of society, that chunk of society that carries Romania.

When people are taking to the streets in protest, they talk a lot about this.

M.S.: Yes, they do. They assume the role of the savior.

B.I.: This is where that sad statement that we have no middle class comes from, “because if we did, we wouldn’t even have 500 people with us here”. Take the “Hexi Pharma” scandal, where they were expecting around 10,000 to 20,000 protesters. They’re reprimanding the fact that there weren’t that many people in that square. They believe that if Romania had a middle class, they would be morally obligated to attend the protest.

For them, that is the proof that there is no middle class.

B.I.: Exactly.

Still, what is the political role these people had in the recent past? Did you also talk about politics with them?

B.I.: We talked about it, but many of them say that they find it strange to see that this moral awakening happens only when the events directly target the middle class. Some of them even say that it was then they realized they were part of the middle class, when they took to the streets and saw that the people next to them shared their values. They started with the protests for Raed Arafat, and for Roșia Montană. Ecology and health are two subjects that keep popping up in discussions with the middle class. Then, there was “Colectiv”, which is the most recent case and has become the most discussed subject. They said that they somehow felt wrong for not getting involved up until then. They feel a type of cohesion forming, but they’re still quite uncertain about what a political alternative to the present state of affairs should look. They’re more civically than they are politically involved.

How much do they talk about emigration?

B.I.: Most of the people we talk to are people who have already consummated their dream of leaving the country. They either left and came back, or realized their dreams, from a material standpoint, right here in the country. We did encounter two or three cases, not as many as I had initially expected, but right now pretty much nobody’s planning a more definite emigration solution. This used to happened five or six ago, not so much now.

I asked you this because it is one of the main reasons given to the argument that we have no middle class: “Those who should make up the middle class have already left”. That’s the general discourse.

B.I.: That’s not really the case; if we analyze the situation a bit we see that it was the young proletarians who actually left.

I, for one, have definitely overcome my condition. But I don’t really know where I stand right now. I’m not back there anymore, but I have no idea if I’m in the middle class or not. Sometimes when I look around me, I wonder if I just don’t make too much money and I’ve simply been too lucky.

[S., 30 years, photographer] – interview by Ștefan Lipan

Was there any type of middle class during communism?

B.I.: This is one of the questions that our colleague, sociologist Cătălin Stoica, suggested we asked. And we did ask it in our interview guides. Most of the people we talked to, who were alive during communism, confirm that there was a middle class and then they go about mentioning the consumerist practices that happened. Let me give you an example of an interviewee who lived in northern Bucharest, Băneasa (translator’s note: Băneasa is the location of Romania’s largest airport). She said that there was a clear distinction between the children of workers, of those who handled the luggage, and the children of the personnel who traveled abroad. She used to see this distinction on T-shirts, for example. The ones that had logos on them and inscriptions in foreign languages belonged to those who got out of the country. And rest of the T-shirts, the ones that showed no signs of Western consumerism, belonged to the children of the proletarians. Consumerism was vital to what made up the middle class before the fall of communism and it’s the same way today. The middle class was embodied by management positions, but also by small entrepreneurs.

How did the communist middle class blend with those who came after? Was there a continuity or are they different categories?

B.I.: We still haven’t worked through the data that we collected. I’ll say this, between the 1990 and 2000, the vast majority of the former middle class individuals, converted their social capital, when privately held companies appeared. Some of them were able to keep their position and transformed it into political capital. But then things changed some more, with the privatization and deindustrialization, many people lost various forms of social capital.

Fragments of interviews taken by the team behind the project “The Material Culture of Romanian Middle Class”

A part of the team behind the project will participate at the European Association of Social Anthropologists Conference (EASA2016: Anthropological legacies and human futures), which will take place in July in Milano. Jennifer Patico, author of a study about post-soviet Russian middle class, will be present at their panel discussion.