On one of the first days of 2022, as I was taking a stroll through Instagram’s garden of information, the algorithms pointed me toward an account run by a bunch of young Ukrainians, who spend their days in the area surrounding Chernobyl. The photos tell both the stories of the people who organize trips and parties in the area, as well as those of the objects touched by the tragic nuclear accident on April 26, 1986. The visual stories stand as a bridge between the death-infested past, symbolically recalled by the abandoned Soviet buildings, and the young generations' present, which is full of life.

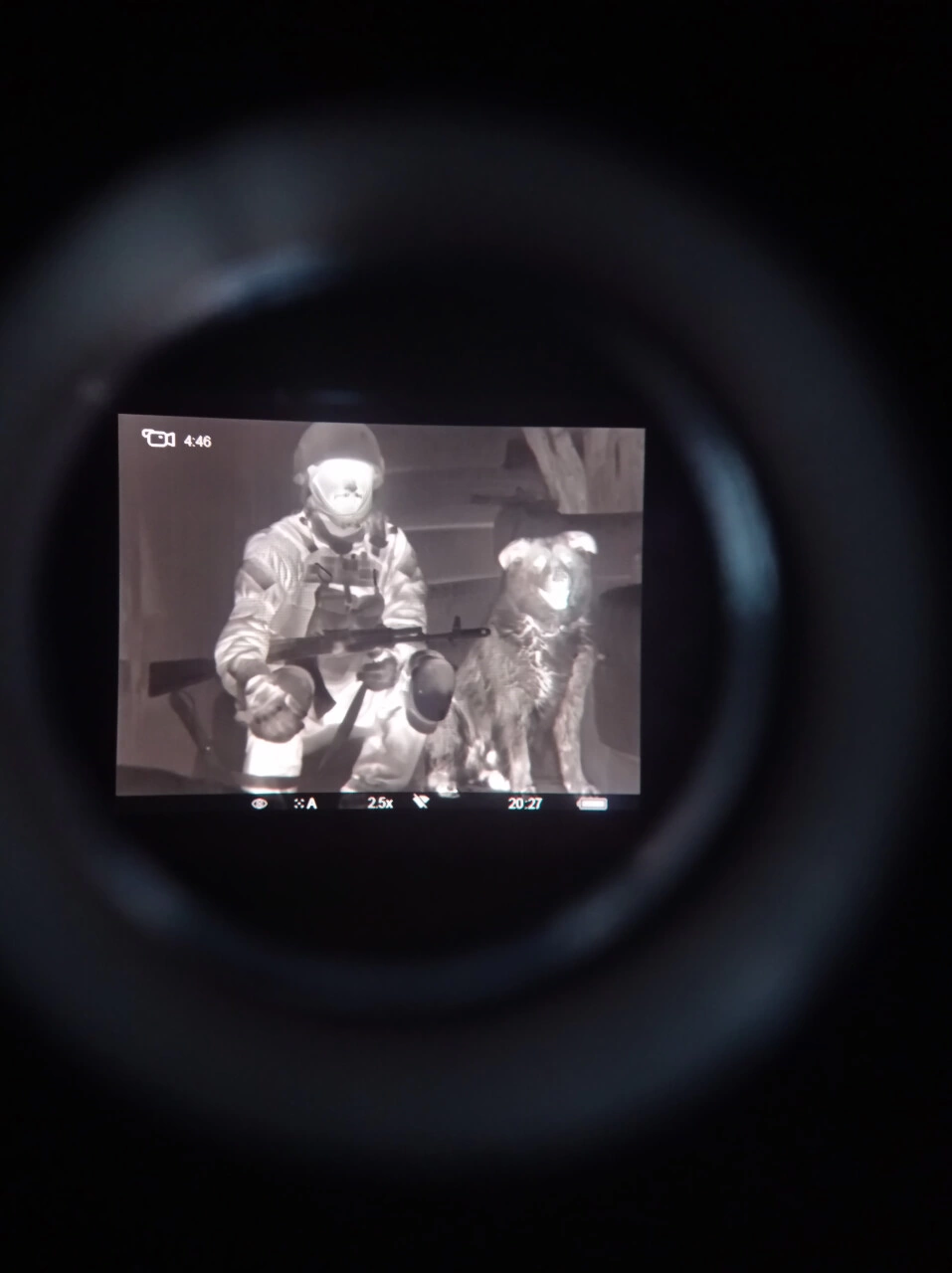

Ever since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the Chillnobyl account has turned into a virtual battleground, where pictures of guns have replaced those of extreme trips at the edge of radiation. I wanted to find out more about the person behind the account, so I messaged them. I got a reply from Igor, the admin and guide to the young people featured in the photos. Although there are seven years between us --he’s 26, I’m almost 33-- I set out to understand his story as the representative of a generation not that far removed from my own, of the life he can no longer return to, and of the reality to which he must adapt.

Throughout the course of two weeks, we spoke for a total of three hours. Synchronizing the three of us (counting the translator) was not easy. Sometimes, a failed attempt would end like this: I’d be in a taxi, rushing to get to my laptop to have the interview, and meanwhile I’d receive a text saying, “No rush, I have to deliver a pack of bulletproof vests, I’ll let you know when I can talk.” When we first saw each other on video call, he had just returned from the funeral of a colleague from the volunteer battalion he’s part of. He was his age, 26. In the meantime, three others have died.

We wound up having a conversation about switching from university student life to soldier life, about what it’s like to be a prisoner of pro-Russian separatists, about the roads that lead to Chernobyl, and about video games.

***

Igor is twenty six-years-old and was born in Liman, a town in the eastern Ukrainian region of Donetsk. At the time, ethnic Russians made up 14% of the population, but the young man says that back then, in the ‘90s, the stories he heard around him did not discriminate between people. “As a child, I made no distinction between Ukrainians and Russians, I mean, it wasn’t considered important,” he says.

In November 2013, Ukrainians started protesting in downtown Kyiv, in Maidan Square, and, within months, this turned into a revolution. At the same time, with Russian support, the separatists started protests in Donbass (the Luhansk and Donetsk regions), which quickly turned into conflicts.

Igor got caught up in this violent picture. It was May 2, 2014, and he was visiting his parents’ home in Liman. In Sloviansk, the neighboring town, the streets had been occupied by machine gun-wielding, balaclava-wearing separatists, who had stormed public institution buildings and were demanding that the Kyiv government hold a referendum to decide the region’s union with the Russian Federation. Their leader was Igor Girkin, a Russian veteran and retired member of the Russian security services (FSB). “I was walking across the town center, where there was an administrative building occupied by the separatists. They called me over and detained me,” Igor recalls. “They saw that, at the time, I was living in Kyiv and had all my tourism gear on me, because I had recently returned from Chernobyl. They thought I was a spy.”

For two months, Igor was held prisoner by the separatists. He spent three weeks on the basement floor of the Security Service and the rest of the time in the temporary detention center of the regional police precinct in Sloviansk. During his abduction, he says he saw around one or two hundred people captured by the separatists. He claims he wasn’t subjected to “severe physical abuse, but many of the other prisoners that I saw were beaten very badly.” In his last week of captivity, they were put to hard labor: they dug trenches and bunkers around the town, for the separatists’ protection. A Radio Free Europe investigation shows that, at the time, Russian leader Igor Girkin had a gang handling the so-called military tribunals that ordered the execution of both civilians and rebels. (Later, Girkin became the Defense Minister of the Donetsk People’s Republic.)

Meanwhile, the relatives of those who had vanished started calling the local institutions. “They received confirmation that, yes, so-and-so is now being held captive by us until further clarification of the circumstances. My friends and parents knew where I was,” the young man recalls. “Sometimes, a phone would be snuck inside and I was able to contact my relatives once a week.”

On July 5, 2014, the town was liberated by the Ukrainian army and the insurgents fled toward Donetsk. They took some of the prisoners with them and left some others behind. Igor is one of those left behind. For some two months following his release, the sound of a plane mid-flight or fireworks would send him into a panic.

After Maidan and the time he spent as a prisoner, Igor says he became much more aware of the relationship between Ukrainians and Russians, influenced by the Kremlin’s politics. He says many in his generation had this moment of awareness. His family also changed their neutral attitude. They started watching the news often, in order to understand what was happening. “Here, I can say a big thank you to our Russian ‘brothers.’ If it hadn’t been for them, there would be no patriotism and self awareness,” he believes. Even though he held no “strong anger toward my aggressors” after being released, he understood that, along with the other Ukrainians, he was living through a turning point in their collective history. “Ever since the year 2014, I realized that [the war] could happen any moment, but it became clearer to me that it would happen very soon only in 2020, when the protests in Belarus failed and Lukashenko became a very close friend of Putin’s.”

While the conflict in eastern Ukraine was bubbling under the surface, Igor was trying to mind his own business. In the years that followed, he became an explorer of Chernobyl, a hobby he’d cultivated since teenagehood, when he devoured books and documentaries on the April 26, 1986 nuclear accident.

In 2007, when he was 13, Igor discovered Stalker, a Ukrainian shoot-em-up adventure video game that takes place in the radiation-filled area. At 15 years-old, he was studying a guide on a forum, where people discussed ways of illegally entering the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone--the name given to the stretch of land contaminated by the Communist-era explosion. Then he took his friends on trips there, like in the video game. He often made the trip on his own. He liked looking at the dome covering reactor number four from above, while he read the Psalms. He says he’s not ready to talk about spirituality yet: “There is definitely a long way to go from disbelief to faith.”

He continued going to Chernobyl for ten years. Sometimes on his own, at other times with his friends, then with strangers, who wanted an exotic tour of a place that already had a magical aura in pop culture and were willing to pay for this. “No one was particularly interested in the history of these places, they just wanted a sort of vibe, a mood,” Igor explains. “I was just a sort of guide, meaning I’d bring people someplace and tell them: Look, here you can safely have fun however you want!” These trips, however, are not for everyone. They can last for days on end and you might have to pass through relatively deep waters. Some tourists turn themselves in to the police when they grow tired and want to make their way back by car. The International Agency for Atomic Energy says that the radiation level is much lower today, even in the Exclusion Zone, which is best visited for short spans of time. In fact, the wildlife habitat areas have considerably increased since humans stopped setting foot there in large numbers. The young man first started advertising his services as an illegal guide in 2021. He’d first meet those interested in the trips for a beer, to get to know them better and figure out if they have some form of connection. Then, they’d set out on an adventure.

He was never afraid of the fines. He says he got caught in the Exclusion Zone a lot of times. “They’d release an administrative protocol and a fine, which, in principle, you could get away without payin in our lovely country,” he says. Before the Russian troops’ invasion the police would make arrests in Chernobyl on a near daily basis, because tourists would sometimes try to take out radioactive items from there, such as elk horns. The authorities were actually faced with keeping a phenomenon in check. The video game Stalker had become a cult title for the younger generations of Ukrainians and many gamers had become guides, to live out their virtual experiences in real life.

With the most curious visitors, Igor would track down the small life stories of the former inhabitants. The villages around the plant remain abandoned to this day and some of the homes look frozen in time. Based on the extent of their curiosity, they had the opportunity to spend weeks living in abandoned homes in the villages or in the abandoned apartments of the town of Pripyat or Chernobyl-2. The latter is a military town where the Soviets built the Duga radar, which sounded like a woodpecker and was meant to intercept a potential NATO attack during the Cold War. “There, we’d find the remains of the unfinished fifth unit of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the radar on the horizon, the remains of the inhabitants’, villages’ and towns’ domestic belongings,” Igor recounts. “I understood how people lived back then. For instance, the abandoned town of Pripyat had a pretty good supply (for the Soviet Union), meaning the nuclear plant workers lived pretty well.”

After having a birthday party in one of the abandoned villages, he got the idea of organizing cultural events that would amass locals of all ages, alongside artists that would lend Chernobyl a new meaning and bring more life to a place where death has been the only subject of conversation for decades.

Before the pandemic, he managed to hold two raves with film screenings. The first one was called Tripyat, the second Chillnobyl. The parties gathered people of all ages and got a write-up from a British author, while a director made a documentary. They scandalized the local community at the time. “Some people were indignant at the fact that we dared organize this kind of fun event not too far from the accident scene; others were saying that they’re cool, that they’d been waiting for something like this for a long time, that they were tired already of always going to kyiv for raves, they wanted something more themed and atmospheric, post-apocalyptic,” Igor explains, assuring me that the DJs played in a hall that was 300 meters away from the dangerous area. “The area where we partied had a lower radioactive background than downtown Kyiv, even.”

The war messed up a spring full of trips he was planning with tourists from two continents.

When the war started, Igor was watching a movie about the Chechen-Russian war, at his Kyiv home. About halfway through the documentary, he read the news on Telegram, announcing that Ukraine had suddenly closed off its air space. Shortly afterward, he heard an explosion out the window. “I woke up my parents, showered, then went to meet a friend who was coming over to Kyiv from Sloviansk, put her on a bus, and sent her to Warsaw,” he recalls. He spent the following three days in a bunker and four more down in the subway tunnels. On the seventh day he signed up for a volunteer battalion. His mother and younger brother left for Rome and his father is looking after their house in the Ukrainian capital.

“I knew that the second a large-scale war started, I’d join a paramilitary unit together with my friends,” the man tells me.

The first time he held a gun was nearly four months ago, on a shooting range with a few of his stalker friends, with whom he used to travel to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Since the armed conflict began, he says he’s tried many types of guns, but the experience itself hasn’t changed or impressed him. “At war, a weapon is a means of protection and annihilating the enemy and not a very interesting item,” the man explains. At the same time, at his 26 years of age, he sees himself as a fully fledged fighter: “I have two motivations: the negative one is that I understand that in such a situation it’s stupid and dangerous to remain unarmed. The second, positive one is that I want to return Crimea, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, and all the other territories that Russia snatched from us.” The Chernobyl area, captured by the Russians on February 24, was released on April 1.

He sees the whole country taken over by the same impetus he’s feeling. It’s a collective image constantly redefining itself ever since the conflict started and they were forced to take care of each other. “Right now, I like the things that are happening to us, this solidarity,” the young man says. He sees a united society, whose citizens are willing to help each other out without a second thought. Before the war, he was surrounded by a collective that always felt inferior to those around. “Ukrainians would often underestimate themselves, they believed everyone in Europe was good and cool, but we’re not like them. Over here, there’s now a joke going around that Europe is Ukraine,” he smiles.

Before the Russian invasion of March 2022, Igor led a leisurely university student life in Kyiv, studying cartography and geodesy. He’d skip classes whenever he felt like it, woke up at whatever time he wanted, played video games sometimes, and then went out for beers with his friends.

His life now looks like this: he wakes up at 7am and works out doing calisthenics and exercises on the horizontal bars with all his battalion colleagues. After a brief religious service, they have breakfast. Then, they start training in battlefield medicine and military combat leadership tactics. They do group exercises in which they simulate pulling each other out of the fire or evacuating stations. After lunch, Igor manages the inventory of equipment they need and forwards it to his friends in Poland, who are helping them purchase them. In the evening, they all gather for tea and a warm dinner.

So far, he hasn’t taken part in any combat, as he’s still in training. His better trained colleagues are going out in the field, from where they’ve already returned victorious: they released a few villages around the capital from under the occupants’ control. Even at war, Igor has found a way to be a guide. He wants to help his teammates with organizing their itineraries and mapping the places where they need to deploy military operations.

I ask him what he believes his life would look like if they lost the war. “We will probably all die. Either we win, or most of us will die, because there is no way for us to run, the borders are closed for us,” he replies. “Sure, it’s scary, but what can you do?”

To whom it may concern. During our last conversation, Igor asked me to forward a message from his friends in Warsaw, who are collecting donations for their gear and civilian aid:

We need your help to provide Ukrainian civil defense with ammunition as well as humanitarian supplies!!!

We buy:

▪️medicine

▪️clothes

▪️bulletproof vests and helmets

▪️tourniquets & hemostatic control equipment

▪️knee/elbow pads & other protective equipment

▪️thermographic cameras and radio stations

Full list and reports of what we have already bought can be seen below in the link.

You can donate UAH, EUR/USD and cryptocurrency.

https://lnk.bio/territorial_defense_UA

This interview was made possible with the support of our Russian-language translator, Veronica Butucel.

Photos: Igor’s personal archive

Translated from the Romanian by Ioana Pelehatăi