If you haven't heard of Forensic Architecture (FA), the research agency based at Goldsmiths University of London, I want to introduce you to them. FA is a combination of an interdisciplinary artists' studio and a newsroom doing investigative journalism. The story begins in 2010, when Eyal Weizman, architect and founder of FA, gathered around him a group of architects, journalists, designers, lawyers, video editors, software developers and activists who use architectural and spatial analysis software to expose human rights violations and state violence. What followed is a decade of extensive investigations from around the world, with and on behalf of individuals or communities directly affected by conflict, police forces or border regimes.

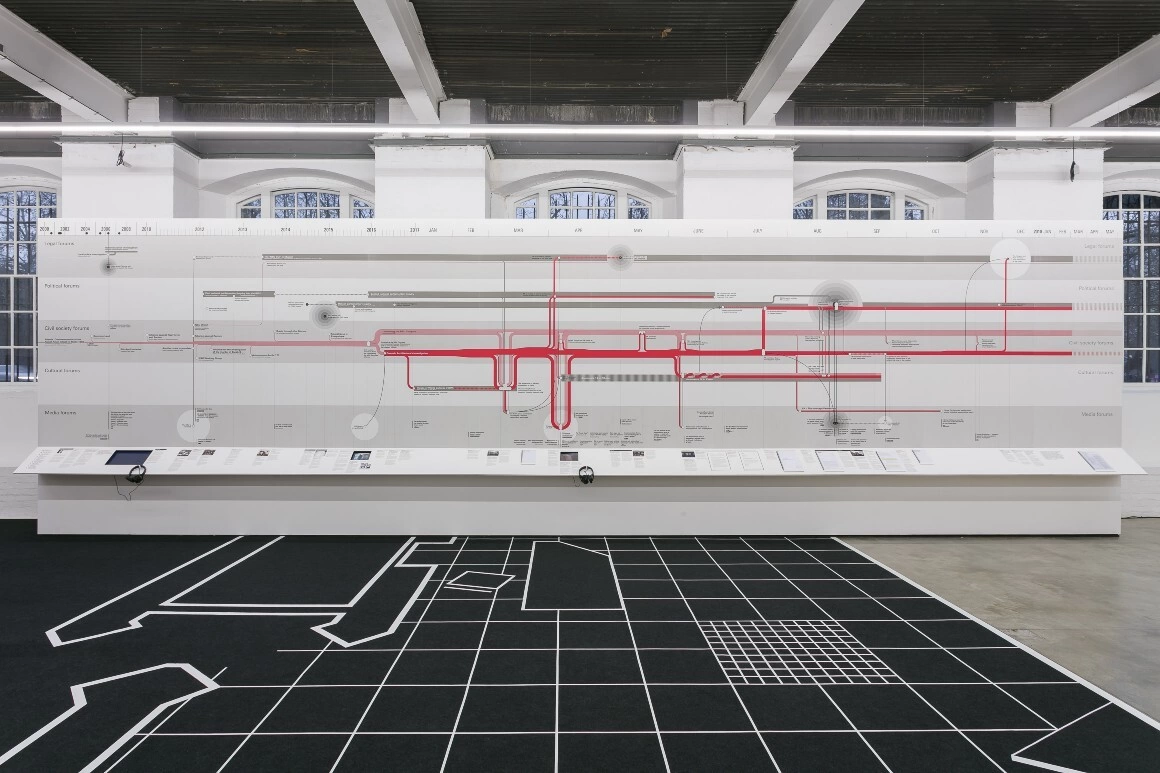

Their cases are sometimes used as evidence in court or displayed in major museum spaces and art exhibitions. "We want to show another possibility of art - one that can confront doubt and uses aesthetic techniques to interrogate," says Eyal Weizman in an interview. One example is the investigation of a murder committed in 2006 by the neo-Nazi group National Social Underground (NSU) against Halit Yozgat in Kassel. Although in 2017 the Munich court ruled out FA's participation in the trial, the group exhibited the investigation at the international contemporary art exhibition, documenta 14, 500 metres from the crime scene. In 2018, the investigation was a finalist for the British contemporary art prize, the Turner Prize.

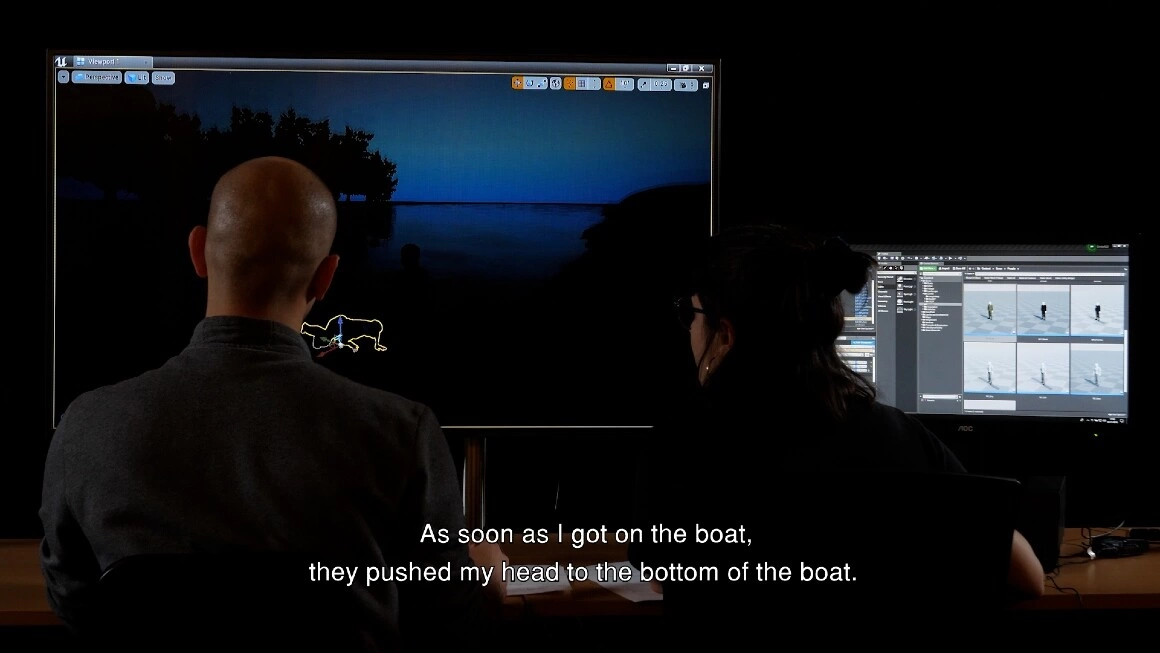

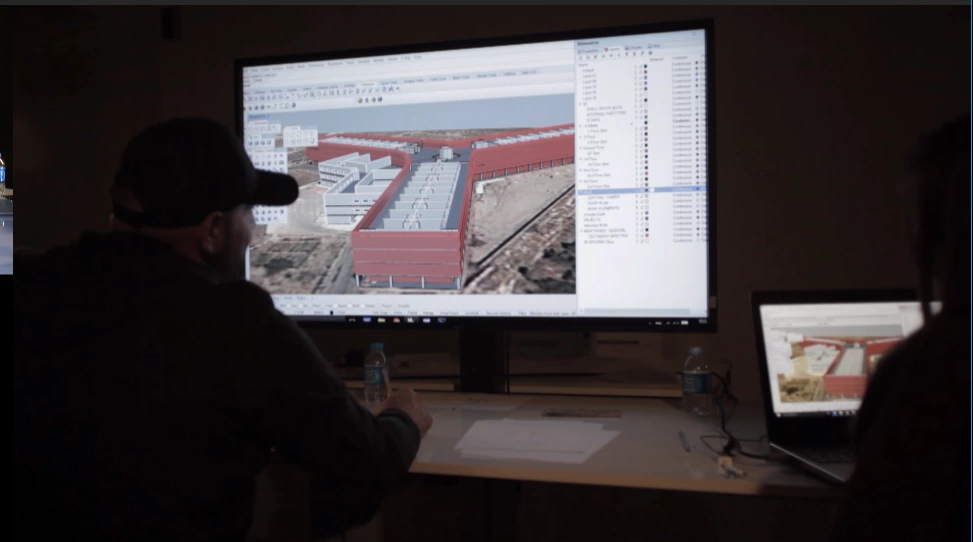

Another FA investigation, Pushbacks Across the Evros/Meriç River: Situated Testimony, part of a larger project on cases of violence against refugees arriving in Greece via Turkey, was presented this summer in a micro-exhibition at the Goethe Institute in Bucharest. The two video screenings featured the investigations of Fady and Kuzey, witnesses describing the abuse they were subjected to by border guards while trying to cross the Evros/Meriç River. Using an interview technique developed by FA, called “situated testimony”, they reconstructed the scenes they described with the witnesses using 3D modelling software. FA use this technique when their investigations lack tangible evidence and proof. In other words, through a collaborative method, FA bring to the surface situations and cases from conflict zones that would otherwise remain in the hands of state-monopolised justice.

Because I closely follow the work of FA, and I wanted to find out more about how they work, I invited to a Zoom discussion, two of the team members Stefanos Levidis, researcher and project coordinator in the FA team, and Andra Pop-Jurj, architectural designer and multidisciplinary researcher. We talked about how they choose their investigations, how they use architecture not to build spaces, but to decode them and understand how violence plays out in urban environments or on borders. The benefits of working with people from different disciplines, or about what role visual evidence plays in court versus displaying it in art spaces.

Scena9: When and why did you join FA?

Stefanos Levidis: I joined Forensic Architecture (FA) in 2016 but I knew the work of the team before joining and I felt it covered a niche that was very interesting to me, between spatial research, spatial design, and a more political kind of practice, also intellectually is quite rich. I had read Eyal Weizman’s books, who is our director and a major influence for me. At the same time I started doing my PhD at the Center for Research Architecture.

Andra Pop-Jurj: I joined almost a year ago. It was actually unexpected because I had my architectural studies in Germany and I did my masters in London, and that’s where I was introduced to FA, but they seemed quite unreachable. But then at the Royal College of Art I was introduced to their methodology and because everything was online during the pandemic I ended up working in quite similar ways, with a lot of digital techniques, open source data, satellite imagery, game engines, and so on.

Compared to architecture as most of us know it, it really challenges you a lot more intellectually and technically.

What does the moment when you start an investigation for a case look like? What are the steps?

Andra: We have a few researchers in charge. They are generally people who have been here much longer. The project initially has to be scooped out by more experienced researchers, set up the partners, and the funding. Our day to day routine very often starts with so many open questions and we need to just formulate them as we go depending on what we find. That's why projects generally get to us because there is something about them that isn't quite right. It's about formulating the research question and then while you start doing things you discover new things so you realize that something is really obvious. Or maybe someone else is publishing an investigation in the meantime and then you have to react to that, or you have to have a response, or you have to include it. It's a very dynamic process I would say. A lot of things change and then once the research process has been finished there is generally a script where wherever media or output we have, if it's a platform it generally starts a bit earlier, but if it's a video or a post production heavy thing then there will be so many changes until the very last minute. Because it's really hard to judge until you see the whole piece together. It has to go through a lot of iterations.

Based on what exactly do you choose and select the cases you decide to work on?

Stefanos: It's a multitude of factors. What kind of agency, what we can bring if we enter a case, if there is something our expertise is not necessary we can't out much, even if it's a very important case we don't really need to interfere. We have to be invited by a community, we need to be wanted in a space. So we don't want to just parachute in and say we are going to solve this problem for you because we know how to. It also has to do with spatial reconstruction or temporal reconstruction or some kind of visual or spatial material for us to analyse. We try to interfere when there is a need for accountability and justice.

Forensic Architecture came about as a reaction to something that was happening in the world, and I’d be curious to know to what extent the classic model of investigating reality was no longer “sufficient” that you created a new model by looking at space and architecture.

Stefanos: To a degree, the practice responded to a change in conflict itself. Conflict became an urban phenomenon and people died inside their neighborhoods, inside their own houses. Violence is enacted not only around urban space but through it as well. Our director and the first team members of FA quickly understood that architecture more than other disciplines has the tools to unpack this new form of violence – render it visible, sensible. And this is how we use space. We kind of do architecture in reverse. We use architecture tools to understand how violence has unfolded around and through the urban environment.

Following that, in more recent years we have seen a high contestation of truth claims. We call our form “truth verification”, which is more of a collaborative form of truth, produced through lateral connection between different actors, fields, disciplines, people. And that’s a challenge we are facing, by producing truth claims within contested contexts.

Andra: You touched on architectural space and urban environments but also just architecture and the building environment as the set for all these forms of violence. Architecture just automatically absorbs all of these, and so, by analyzing the space, I think you can discover a lot more than you might expect.

I sometimes wonder if there is also a kind of educational element to it, to and for society. In a way which we instrumentalise social media or just generally media as evidence, we analyze, formulate and repackage it. I wonder if that also can bring awareness beyond and in everyday people’s lives.

Stefanos: Yes, because we use the tools and the ability to cross check information we receive in our everyday life. I forgot to mention that along with the change in warfare came this new proliferation of images and video and all that which is accessible in social media, to which we didn't have access before. So what we do is use spatial design as a means to make sense of all this material. Navigate from image to image from video to video and through space to understand what's happening in a specific violent context.

How do you see the difference between evidence and testimony?

Stefanos: Recently we did a conference at the HKW (Haus der Kulturen der Welt) to coincide with the launch of our Berlin office, and a very close friend of ours and collaborator, Başak Ertür, described our work as apotropaic magic. As something we weave around people’s testimonies to protect them. In ancient Greece they used to do these faces (objects) outside doors to keep the evil out.

What we do is try to reconcile these two seemingly divorced worlds of hard evidence versus subjective malleable human testimony – the division that courts make very much but also media nowadays. We try to bridge this gap and bring the two in conversation and use evidence to protect testimony. That's what situated testimony does in some ways. This is an effort to gap these two seemingly different realms in the legal sphere and bring them together in conversation. I'm not a legal scholar, so I don't think I'm the person to address your question, but I can tell you how we go about that. Not all the testimonies equal in the eyes of the law, and we try to also take that into account as well. The testimony that we care for is being discarded more and more and being replaced with hard tangible evidence and we want to resist this binary.

Andra: Something that I also learned on other projects that I'm working on is that lawyers often just don't have the means to give a certain snippet of testimony as evidence, so it seems like that's also where we tend to come in, to really turn testimony into something valuable. To place a value where it is really needed.

Stefanos: Sometimes testimony is inherently spatial and there are spatial elements in what a person has witnessed, and these are things that otherwise might get lost. Like the court might focus on what they did to you, whereas if you describe a door, or a wall, or a chair, or a piece of furniture, this is also stuff that can verify testimony, to this level of detail. This is what we try to do with situated testimony – an experiential dimension of the testimony and use it to corroborate.

Do you think that the way you approach investigations at FA through the situated testimony technique also influenced other media platforms of investigation? And if so, do you have any concrete examples? I know that you now collaborate with the Central of Spatial Technology.

Andra: As far as I'm aware I don't know anyone else using the situated testimony technique.

Stefanos: As far as I'm concerned, the only recent attempt that I'm aware of was done by a group of people working on the Polish-Belarusian border (Border Emergency Collective), which included a person that formerly worked with us and who was in close consultation with us throughout the whole process. So, it's a technique we came up with, but, as with all our techniques, we disseminated it to a wider constellation of researchers, if you will. Very similar to what we did in Evros/Meriç River, as I presented it in Bucharest. It was one case of a series of pushbacks and restrictment of migrants and asylum seekers at the border of Poland with Belarus. They basically use the same workflow we are using and we helped them to come out with their own version of the technique.

In some cases, when there is a lack of evidence you use open source technology like Google Earth or standard architectural softwares, tools that are free of use so anyone could access them. How much does this class of visual evidence weigh up when you are called into court? I know that even though they seem not to take into account the visual evidence that you bring them, I cannot not wonder if this is something that could change in the future.

Stefanos: There are different responses we get from courts. Depending on the court, depending on the context. Of course, our practice is something that's kind of new still and you have to brace the trail and make ourselves accepted in legal fora and this is one of the reasons why we don't consider courts the only output of the work. We use the term fora for these places where we socialize the work with the evidence we produce.

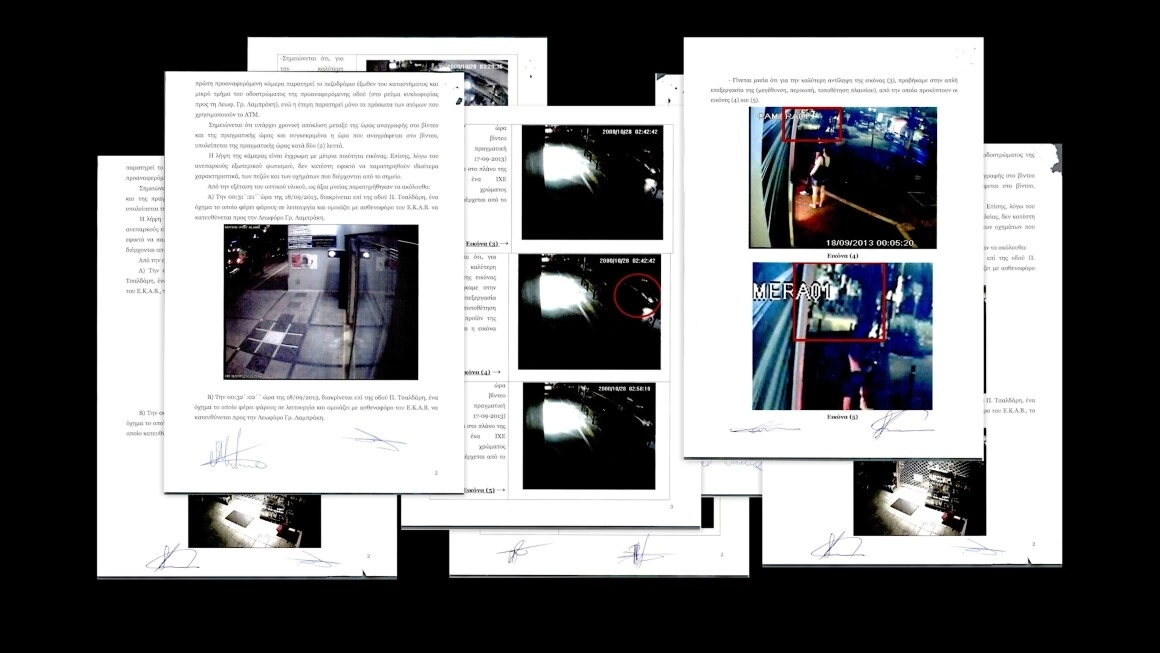

There have been cases where we successfully presented evidence; it was accepted, taken into account and has weight towards the final ruling of the case. One of this cases was of the 2013 murder of antifascist raper Pávlos Fýssas in Athens. Our work in the trial was crucial and was accepted and taken seriously.

In other cases, we have been excluded from courts, so it's a case-by-case scenario. There is still a degree of media literacy that needs to be installed in courts before our work is taken for granted. We still have to fight every time, to prove why it's worth being shown in the court. Because courts associate montage and editing with doctoring material and contamination. They have different chain of custody rules, that you have the video as it is and leave it on the test of the court without ever unselling and unboxing. Whereas what we do is really go into the videos and analyze them to a degree so we can see things that otherwise are not visible. And that sometimes is a problem for a court, but it's not a problem for society, for the media or for art spaces. Depending on the case, we look for different outputs.

Moving from the court context to the exhibition space, do you feel that it brings a different level of understanding to the investigation when you see it installed and exhibited in a museum or a gallery?

Stefanos: Sometimes a work is created for court and we show it in an art space and it fits awkwardly – and vice versa. But we see museums and galleries as spaces with potential political agency. Spaces where we can discuss our work and achieve change and accountability in a similar way to courts – or rather in a different way to courts, but similarly important to courts.

A recent example is our contribution to documenta 14, in 2017, where our investigation into another neo nazi killing, that of Halit Yozgat by the NSU, was excluded from court and we chose to show it at the documenta in Kassel, 500m away from the murder scene. Documenta became the court and people started to come and see it and the whole society of Kassel visited it and understood what happened. The police chef who was responsible for the investigation back then had to come and sit in the museum and look at the video and respond, etc.. It kind of replaces the court, while at the same time asking questions that a court would not have asked. So they are very much complementary sometimes, even though they seem like very different spaces.

It's also an opportunity for us to take a step back and reflect like you said on the work: Am I missing something?, or discuss with people who are visiting and see you at the exhibition opening and say, Oh but I have this question and that question. It's also an exercise for us to take a step back and reflect on the work itself and how this is received by the audience as well.

You managed to visually deconstruct complicated investigations in quite an understandable way. Is this also the result when people with different skills from different disciplines come together? At the same time, I’m wondering how non-professionals perceive something that is so dense and multilayered. Stefanos, I remember you saying at your keynote talk in Bucharest, that the only ones who seem not to understand your work are authorities and governments.

Andra: I think having so many people of different backgrounds in the office is such a diverse place – not just professionally, but also just everything that goes out gets so many different iterations. It starts from something quite rough or raw and by the end it's edited so much. This is something also that I'm learning to synthesize and cut through the bullshit. Clarity is a priority. I guess it's also very much a curatorial exercise. How do you want to convey the result and what makes most sense to present and what order is the chronological narrative of what happened. There are so many different approaches as well depending on the kind of awareness or consciousness that you want to create in your audience.

Stefanos: We are learning very much from each other every day and that's because we come from different backgrounds. There are people who understand differently and know how to do things differently and that's something that contaminates the rest of the group. We often meet to discuss, we have peer reviews. One person’s expertise will bleed into the other in a way that's fertile.

No matter how many people we get on the team from different disciplines, I still think governments will decide not to understand our work. I did not remember to have said that but as long as it's uncomfortable for certain state agencies I think it will remain on the rise.

Working in an interdisciplinary and collaborative environment with people coming from different disciplines might become an essential tool in order to decode and expose cases of human rights violations; an alternative to the traditional state-monopolized way of producing evidence. How do you see it?

Stefanos: It's important to also stress that with almost every investigation there are things that we cannot do because we don't have the expertise, in which case we will collaborate with experts from other disciplines or universities from other parts of the world. When something is outside our field of expertise we will collaborate with a ballistic expert, oceanographer or an acoustic expert. We try to have an understanding of what's possible and what tools are needed to do that but quite often we collaborate with other people.

Andra: I think that also helps to build legitimacy.

I visualize this type of collaboration like a huge forest connected through its branches, touching each other when the wind is moving, as well as from the underground roots.

Stefanos: I like this image.

At your keynote talk in Bucharest you said that artists have different degrees of sensitivity when it comes to analyzing or producing images.

Stefanos: Our practice is an aesthetic one, and by aesthetic we go back to the Greek root of the word esthesis which means to sense. Not only sense with your eyes, but sense with haptic methods, with your ears, etc. We worked closely with Lawrence Abu Hamdan who works with sound. It's not just images, it's again what can be sensed or what can be rendered sensible in the public sphere.

To recreate a timeline of an event for evidence seems the most challenging task when there are no images. I would like to talk about how memory is attached to sound or how sound becomes the link between images, materials and bodies. What kind of technological techniques can be involved in the process of stimulating the memory for the witnesses in order to draw the line of an event?

Stefanos: I'll give Lawrence's example because we worked with him to model the prison of Saydnaya, in Syria, where he developed a technique to account for the total blindness of the people who were held in that prison. They had no access to light, so they couldn't see the space they were held in. Other experiences were either haptic or auditory. He used different kinds of sound, different echoes, and materials. The way they sounded helped the team recreate the architectural space, but also part of the experience.

Torture is very much effected through sound in some cases. In other cases, we worked by listening very closely to what is being said in a piece of footage, to understand what's happening, or to link different pieces of footage or audio and video together. So you hear the same voice or the same gunshot, and these become signatures like fingerprints that allow you to stitch things together. And when it comes to artillery sounds or ballistic sounds, there is a layer of forensic analysis to be done and we've done that in the past with Lawrence and with other audio specialists. To understand what kind of gunshots we are hearing: do we hear live ammunition, is it automatic weapons, semi-automatic weapons? and compare that to weapons we see carried by certain state agencies in a piece of video and photograph, etc..

Every time we speak to witnesses they describe sounds and hearing things like screams or specific types of gunshots, which scared them. This kind of generic description needs to be hammered down and I say generic because usually they come from a place of trauma, like detentions or conflicts, etc. They are memories that are very charged with fear and pain. So we try to work with sound to substantiate these testimonies and understand what they actually contain, what kind of information they can give us.

So sound is very closely linked to memory, maybe even more closely then image itself because it comes at a moment when looking is not a primary function of your body. Normally you hear things that are stronger than what you see. Remembering things that are stronger than what you saw at that time. This is either because you can't see, you are in a cell, or because it's such an acute sound that it really sticks out of the rest of your senses at that time.

We worked a lot with what would be audible from a specific location, going back to the National Social Underground (NSU), the investigation that I discussed earlier for the documenta 14. But a more recent investigation that we did is on the neo-nazi racist killings in Hanau, again in Germany, where a gunshot would be audible and whether the police chooses to not hear the gunshot. Gunshots were certainly audible from where the police were sitting and were supposedly not heard. We compared the type of noise a gun makes with the ambient noise of the street outside, to the location where the police were hearing. Sometimes people don't hear because of structural reasons like the police don't hear specific sounds when they hear other sounds so all these nuances are things that we try to flesh out in our practice.

It seems to me that your practice and what you do is so much about being present. Like talking about sound you really need to be super focused, but more than that you need to be really present in the moment. I'm not referring specifically to the police or the witnesses but the way you approach the technique of listening, or even from looking at images or videos.

Andra: Because we often have to watch the same materials and analyze the same sounds or same footage so many times sometimes it can also be quite traumatic. Up to a certain point, if you do it too much it also doesn't make any more sense. It can be quite a laborious process because at the same time you want to listen and you really want to find what you are looking for. Or sometimes you listen again and you find something that you haven’t heard before. It takes a lot of attention. Sometimes also working with different experts can help to highlight certain sounds over others. In the case of Hanau I think it was important to isolate the different sounds and the soundscapes of the city at night in order to be able to see from where the sounds are coming from and where it was received.

Stefanos: Let me go back for a moment to your previous observation, about being present. I think we are trying to fill a gap that's created by a certain structural absence of the authorities. A lack of access on the side of civil society. Authorities will see a crime scene and prohibit you from accessing it, from being present not only on the scene itself but from being able to make claims that will support the victims, their families. Being present on their side. So our practice really tries to undo this spatial configuration where you are not allowed to access, to see this violence and to offer support to those who endure it. In this sense it's a lot about being present where you are not supposed to be present, so we try to get into these places that are not supposed to be reached.

Our work is also about undoing the distance that is designed into the systems that perform the crucial part of violence.

Your PhD thesis Border Natures (2020), interrogates the entanglement of border defense strategies with the natural environment at the external borders of the EU, with a focus on the Greek case. In the acknowledgements section you give special thanks to your family by saying that they introduced you “in their own curiosity and a fascination with border landscapes, as well as a fraction of their visual sensitivity and imaginative capacity.” How did you decide to do your PhD on this subject and second, what conclusions or questions did you leave when you finished your thesis?

Stefanos: The acknowledgement is there because they took me to those places. Like Andra says, when you spend time close to the border it fascinates you one way or another and it's something that you can't comprehend. Especially as a kid, Ok, why can't I go behind this line?

We have a house at the border with Northern Macedonia and Albania, and in the 90s Albania was collapsing basically, so every day you would see people come from the forest and when you didn't see people you saw stuff they left behind. No matter where there is a war or a reason to leave people would come to cross Greece. My interest was very much conditioned from where I am.

This is what I write about, how violence is designed into the natural environment and performed by the natural environment. So it's kind of outsourced and the responsibility for this violence is also absorbed by the natural environment. We speak of natural borders nowadays and if there is one conclusion is that there is no border that is natural. The nature at the border is hybridized in many different ways that you can't discern what is nature from what is culture from what is military infrastructure, technology, etc.. So this is what I call border natures, is this hybrid result of these intense interactions and lateral connections that you can't quite trace.

Talking about the fascination with borders, especially if you were born near a border between two countries, I think one might have this fascination, but maybe not the motivation to do something about it.

Stefanos: To move is the most natural thing you can do on this planet. To change places and to be able to move freely from place to place without having to die trying to cross. That is what creates the frustration. How can someone tell me I cannot go there if I need to. As a kid I wanted to go but I didn't need to but other people needed to do it.

The last line from my PhD says that the only thing that is natural about borders is crossing them.

I know FA planted some seeds of small collaborations with NGOs in Gaza, Mexico, Columbia, as well as with a group of people who fled Ukraine and that now are living in Berlin. Is it part of FA's strategy of expanding its branches of offices to cover an area where journalism alone cannot?

Andra: The intention is not to grow so much, but rather to educate others in their methodology so that they can then appropriate and use them. They call them satellite units, led by researchers who used to work here [in the office] and have completed a project. I think it's maybe also a product of the pandemic with people having gone back and realize it's much more important to be on site and to do the field research yourself. I appreciate the idea of not trying to expand and monopolize them all but rather just give people the tools.

This actually brings us back to my original question about whether FA methodologies can influence other platforms or initiatives. Now I feel that I have the full answer. You are not simply borrowing a technique that has already been developed through other projects and seen to work, but you try to apply it in your own local context.

Andra: There is a very exciting investigation coming out next Tuesday. I can't say much about it but it's a very important one (Editor's note: the investigation can now be seen here). For this one they had to recreate this methodology in Palestine and it had to be done very differently. It was a mix of what we had until now and I think it will always be very customized to the situation. We are keen not to do repetitive stuff over and over again. For instance, the investigation on the Aegean Sea, working with such a big terrain and doing those geo exercises in the open Aegean Sea was something very unusual in a way, because normally we are used to locating something on a street, google maps, or in a built environment. But the scale of the sea was a completely different one and also the margin of error that we had to account for. It's always a slightly reappropriated technique.

Stefanos, based on your experience and as a long-time member of FA, what would you say to someone who is new to the practice or in the team?

Stefanos: For me it has been a very fulfilling journey. It has highs and lows because you deal with other people's trauma and you go through material which is stressful and you can have burnout moments. What really puts things in perspective is when you actually tangible help people get justice and change things in a society as it was with the case of Golden Dawn investigation when I joined another 200.000 people outside the courtroom of Athens in cheering about the results for which results we had contributed. At that moment I felt really full with the job that I had done in the past years.

Andra: It has been fulfilling on the cases I have worked on as well, rather than actually building a building.

Stefanos: We are misfits of architecture. We all tried to work in an architecture firm, most of us. We respect that profession but it wasn't for me, I got bored very fast. It’s not to say that architecture isn’t interesting.

Andra: Exactly.

This interview was conducted in English. It was edited and condensed for the sake of brevity and clarity.

You can read the Romanian language version here.