Meeting with Romanian Jews who are successful professionals abroad always challenges one to counterfactual exercises. What if these people had stayed in Romania? Would they have been where they are now? In most cases, probably not. (As I’m writing this, I’m sharing a car with doctor Zvi Bercovici. He is a specialist with an impressive scientific career and the personal physician of Benjamin Netanyahu, prime minister of Israel. He was born in Târgu Lăpuș to a family who suffered during the Holocaust). Would our country have been better off had he stayed? Probably. Would he have lived a quiet life? I’m certain he wouldn’t have. Only the dead can rest under fascism and communism.

Elie Wiesel once said: “Did I leave (Romania)? No! As a writer and a teacher, I must speak the truth. The world “leave” is incorrect here, it’s not true. We were banished, as if we were mangy dogs. Nobody had any compassion for us! And when I return, for the second, or third time, I return because I want to. Is something beckoning me to Sighet? Why wouldn’t it? This is my home, this is where I spent my childhood years. It’s where I learnt my first words, my first prayer, and my first song about Jerusalem. This is where I dreamt of a Jewish state and that Messiah would come and save all the people. But when I come here, I can’t stay. I have a strange feeling that I need to run. Maybe you know why?”

These days, we talk more about the Holocaust and anti-Semitism. We talk more openly, but judeophobia is rampant again. It was probably never really gone, just well-hidden.

That last question sounds different depending on the times. These days, we talk more about the Holocaust and anti-Semitism. We talk more openly, but judeophobia is rampant again. It was probably never really gone, just well-hidden. Where do you look to for the right answer? On September 10, 2017, Sighet hosted a march in memory of Elie Wiesel. It was a touching moment, where 1,500 people joined the march, a few hundreds Jews from Romania, Israel and other countries. The rest of them were Christians, local people mobilized but the city hall or there by their own volition, to mark the moment. While I was holding a candle and walking to the train station where the Sighet Jews were deported in 1944, a handsome, well-dressed, young man, crossed the path of a group of peasants wearing national costumes and muttered: “F*** the k*kes! Good on Hitler!” Nobody paid too much attention to him, because he was alone. But during the Holocaust, people like him did matter, and they were angry and ideologically focused. You never know, with anti-Semitism, as well as with other radical “-isms”. A handful of people can cause a lot of destruction. So, the authorities should tone it down with their triumphalism and minimizations. In the interwar media, they used to monthly quote discourses by politicians who stated that Romania was a tolerant and welcoming country, and that it didn’t have an issue with anti-Semitism. We all know what happened later, especially after 1938. But even before that. During the interwar period, the same media used to chronicle, also monthly, many of the severe and violent anti-Semitic incidents; either physical or symbolic, against the Jewish people. Things didn’t end after 1945. This history will one day be written.

If we look at the polls and we’re being truthful, we can acknowledge that in the last decade, not much has changed in terms of perception; not since anti-Semitism and Holocaust education started being implemented. But this doesn’t mean that education is futile. It could have been worse, in these troubled time we’re living in. Times when the antidemocratic trend seems to go viral in Europe. The polls are telling us, once more, that the changes in perception don’t happen effortlessly and that it takes patience and skill. And education is not the same as rallies’ propaganda, nor authoritarian learning.

Since the time of the Holocaust, we know that misleading and passive majorities don’t necessarily matter. What mattered more was the criminal behavior of state structures and the distructive fury of an active minority. Romania’s biggest triumph after the Final Report of the „Elie Wiesel” International Commission was that there was slight change in the attitutide of the state, and the political and intellectual elites, towards the issue. Anti-Semitism is hard to fight, but at least the public-level manifestations can change. This is what I was told by Rafael Schaffer, Romania’s first rabbi, and Liviu Beris, the well-known Holocaust survivor, with whom I shared my morning coffee on a quiet Sighet day.

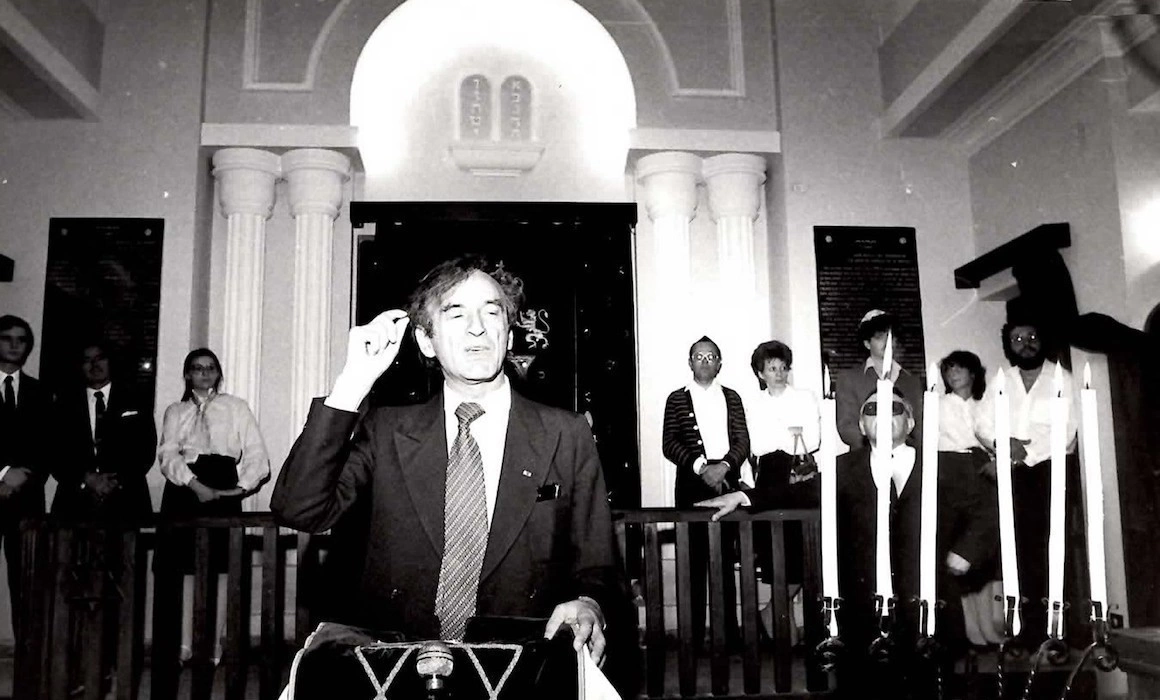

When Wiesel was speaking the aforementioned words, it was the year 1984. The Auschwitz survivor was in Sighet, after being invited by the The Federation of the Jewish Communities, lead by Moses Rosen. A few years back he was brave enough to extract the Holocaust commemorations from the limited Jewish sphere. Today we know that it was a type of freedom with strict borders. The communist regime had started to publicly speak about the Holocaust in Northern Transylvania, but it continued to stay silent about Transnistria. The national clashes with Hungary had transformed the tragic story of the Transylvanian Jews into tinder for the propaganda war with the neighboring state. And Rosen and the communist authorities were using each other. The communists were crediting the myth of the universal Jewish influence and thought they could use the situation to gain the favors of the United States, Israel, and other Western states, and achieve some foreign policy objectives. And Rosen was also taking advance of the moment to increase the Federation’s visibility and expression. Back then, the Federation’s History Center (which I am honored to lead today) published a small paper on the Transylvania Holocaust, that stated, inside a scientific environment, certain assertions that had not been heard up until that point in the communist historiography.

Between 1944 and 1948, when Romania was transitioning towards communism, you could speak about the Jewish pain. There were biographies being published, the times’ newspapers told the stories of some of the people who returned from the camps, several mass graves were dug up (in Sărmaș, in the Bungur Forest, at Stânca Roznovanu, etc.), and trials of the war criminals were being publicized. But after 1948, there was none of that. The archives were closed, and the subject became an ideological taboo in the ‘60s, following the communist regime’s nationalist flavor (influenced by, among other things, the exoneration of several nationalist intellectuals who were active during the Antonescu regime and the interwar period). A book on the Iași pogrom was written in the ‘70’s, with the Communist Party’s indulgence, but it completely blamed the Germans for everything. The Securitate had elaborated a paper on the Holocaust in Romania, for internal use, where the Germans were seen as the main culprits for the crimes. Crimes which we know today were committed by the Romanian authorities. Jean Ancel was strictly followed whenever he came to Romania in the ‘80s and the language used by the Securitate in the files on him have a stunning resemblance to the language used by the Antonescu regime.

Elie Wiesel was also followed during his visit to Romania in 1984. The files that are today in CNSAS (National Council for Studying the Securitate Archives) are proof of this. But Wiesel had the advantage of an extraordinary international reputation and the protection offered by his status as a special delegate of the American president. All things aside, he had the courage to say whatever he was thinking, no matter the situation. He believed that it was his duty, especially after he saw for himself the effects of silence and moral numbness during the time of the Holocaust. The immense moral authority that Wiesel was enjoying, one that I myself have felt as a member of the Wiesel Commission, was gained not by ethical triumphalism, through a feel-good story of good triumphing over evil. It was attained through the courage to speak about the immense moral decline throughout the Holocaust, when one of the reasons such evil was made possible, was good people giving up.

Main photo: Elie Wiesel during his 1984 visit to Romania. Source: Archives of the Elie Wiesel Memorial House in Sighet

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea