Håkan Tropp, an expert in water-related policies, talks about the diplomatic role of water in times of peace or war, why we don't value it as a resource, and how we can mediate the risks associated with its disappearance.

A report by the Global Commission on the Economics of Water estimates that by 2030, the demand for fresh water will exceed supply by up to 40%. This is due to poor water resource management, the destruction of natural ecosystems, climate change, and population growth. It’s a harsh reality, one we will have to confront sooner or later.

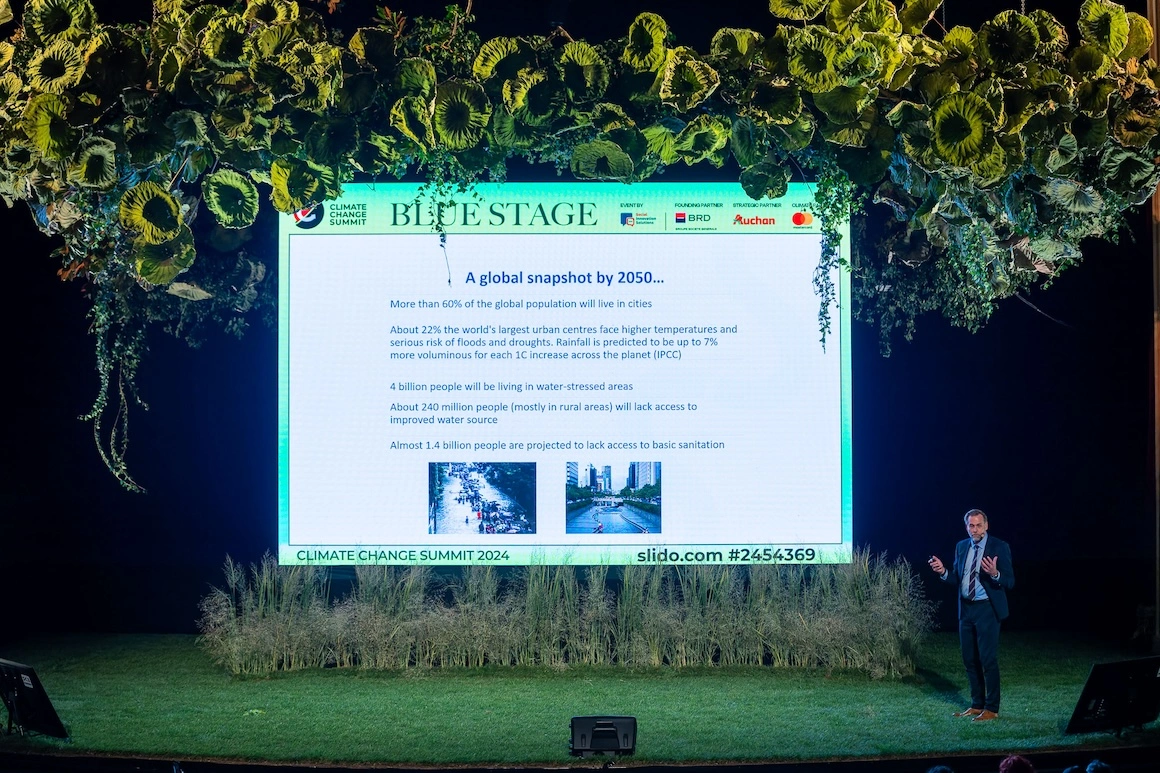

Håkan Tropp spoke about this at the third edition of the Climate Change Summit, a conference on the environment and climate change. Tropp is the Program Director at the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI). With over 20 years of experience in governance policies and institutional development, he has led several international programs that, in one way or another, are related to water. He has provided consultancy on this topic in countries across Asia, Africa, and Europe, and he is in charge of the International Center for Water Cooperation (ICWC), an institution created by SIWI and UNESCO.

"I got fascinated by water because it underpins so many things: nature, the economy, culture. It doesn't matter what you work with, you can always find a water angle to it. That’s why I think I've stayed in this field for so long, because when you work with water, you can always find new perspectives", Tropp told me at the end of the first day of the summit, after he and other guests addressed various aspects of climate change on the stage of the National Opera in Bucharest.

In his speech, the expert spoke about the impact these changes will have on humanity's access to water. He discussed how we will increasingly find ourselves with too much water in one place (such as the floods in Europe this fall) or too little in another (such as the drought in Europe this summer).

Tropp explained that access to water is one of the areas where we manage to cooperate, even if we struggle to do so in other fields – although there are still many challenges here as well. It will become an even greater issue because water is a resource we need to share, especially now as it becomes increasingly scarce. Four billion people face severe water shortages for at least one month each year, and two billion lack access to clean water. It is time, the expert says, to move from solving water-related crises to mitigating the risks surrounding it.

Starting from these ideas, I spoke with Tropp after the conference, trying to better understand his vision, where we are with the cooperation he talks about, and what we can do for a future in which everyone has access to quality water. Here are three ideas that stayed with me.

When it comes to water, it’s as if we’re suffering from blindness.

While climate change and the crises it causes are receiving more and more attention, issues related to water — from access to its “health,” so to speak — are still not as prominent on the public agenda.

“We are so used to water and we take it for granted. It's this attitude towards water that it will always be there and we can take however much we want, we can pollute it in any way we want and it's not a problem,” says Tropp.

To some extent, there’s a visible change, the expert adds. The subject is increasingly present in high-level discussions about environmental policy development, as well as in the media. But it’s not enough, and there’s this perception still that water is like an endless well.

However, Tropp adds, “it's going very slow. Too little is being done about it I think. Honestly, I don't know why there is this water blindness. I don't understand it because it doesn't take a lot to also take water more firmly into theequation. Water is this resource flowing around in nature and society. It's something we need to share. There are bigger decisions we need to make and we need to make sure they are the right decisions.”

Water is a complicated topic

“Water management policies are complex”, acknowledges the director of the water management research and consulting center, SIWI.

Clearly, water is a resource that we all need. People need it for personal consumption, states use it to keep cities and society functioning, and companies need it for industrial purposes to produce the goods we consume.

“We tend to compartmentalize water issues, which leads to fragmentation. Typically the different policy sectors don't coordinate. So you have a lot of policy misalignment.” For example, there could be measures by the environment ministry aimed at reducing water consumption, alongside measures from the agriculture ministry that increase water use. Meanwhile, consumers—whether they’re city residents who want drinking water or farmers watering their crops—don’t think about water issues. All they know is that it should be available and as cheap as possible.

“And, of course, as water is getting polluted, there are potentially even more future costs for restoring that water to its original quality.”

So, yes, in such a landscape, it’s complicated to come up with policies that please everyone. And this is just about a state’s internal policies. But lakes, rivers, seas, and oceans don’t recognize borders. Let’s talk about “water diplomacy,” another topic Tropp knows a lot about.

Water diplomacy policies bring together many stakeholders (from states to NGOs, experts, or private companies) who try to find solutions for better water resource management (whether it’s the water we drink, the waters we navigate, or the water we use in industries). I know, it’s far from a “sexy” definition or an easy field to approach, and it’s understandable that it might not come up as a topic at your next outing with friends—but it’s extremely important.

The Indus is a river that flows through multiple states in Asia, including Pakistan and India. In 1948, during the Indo-Pakistani war, rights over the use of these waters became a source of conflict. After years of failed negotiations, on September 19, 1960, the two countries signed The Indus Waters Treaty, which regulates access to the river. This agreement is still considered one of the most successful examples of water cooperation.

"There's probably more than 300 international agreements on shared waters," and some of these agreements, explains Tropp, are between countries that have tense or even conflictual relations. He gives the example of India and Pakistan. Since Pakistan is downstream of the Indus River (and some of its tributaries), there is an understanding with India regarding the water flow that reaches Pakistan.

More recently, we can talk about The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which, once completed, will serve as one of the largest hydropower plants i4Textboxaddexpandmore-dotsn the world. The dam is built on the Nile River and is expected to double Ethiopia's energy production. (Currently, only half of the country's 120 million people have access to electricity.) Here you can see how complex diplomatic relations around water can be. Egypt and Sudan, countries located downstream of the Nile, criticize the dam because they fear it will reduce the amount of water reaching them. Egypt, for example, sources 97% of all the water it uses from the Nile, and the United Nations warns that Egypt could face severe water shortages by 2025. Parts of Sudan are already highly vulnerable to drought, and the ongoing civil war there worsens the situation.

The dam project began in 2011, and negotiations between these three countries have continued ever since. In 2021, talks stopped but were resumed in 2023. Tropp acknowledges that it is a controversial project but is pleased that the countries are negotiating.

"I would say it's still more cooperation than conflict when it comes to these international rivers. So, it’s a positive message."

In theory, water can also be a starting point for discussions with closed-off states, but in practice, this is often a challenging goal to achieve. "It's very difficult. There were some diplomatic attempts to initiate discussions about the Han River, which is dividing parts of North and South Korea. It wasn't realistic." This is because, he continues, it is impossible to collaborate with extremely closed dictatorships. This also has negative effects on water resources. Moreover, it's very difficult to act without state transparency and when voices that might "sound the alarm" about various issues are oppressed.

Water is also present in conflicts. War creates pollution that can impact rivers, lakes, deltas, or seas around combat areas, either directly (explosions leave particles that settle in water) or indirectly (traffic rerouted because of the war can cause imbalances in ecosystems and increase the amount of waste inwater). This is happening now in the Danube Delta, both on the Ukrainian and Romanian sides. In other armed conflicts, water sources can become military targets. In June 2023, the Russians were accused of destroying the Kakhovka Dam, causing floods along the Dnipro River. The waters covered several villages, hundreds of people and thousands of animals lost their lives, and the overflowing river carried further projectiles and landmines, some of them undetonated.

In Gaza, Israeli forces have destroyed hydrological infrastructure, massively reducing Palestinians' access to water. In November 2023, UNICEF estimated that, on average, a resident of Gaza lives on just 3 liters of water per day, far below the UN's emergency standard of 15 liters per day. (It may seem like a lot, but this includes all the water we consume, from drinking to cooking to personal hygiene, etc.) Before October 7, 2023, the Gaza Strip received 49 million liters of potable water per day; now, this has been reduced to 28 million.

There are a number of international laws stating that water used by civilians cannot be targeted or weaponised in a military conflict. However, in practice, no agency can enforce international law if states do not want to comply, Tropp explains. "In a way, it’s like having a toothless tiger. The UN doesn't have a bite."

Thus, on the battlefield, water continues to be used as part of military strategies. The response to this, Tropp believes, should be stricter and harsher actions against transgressors once the peace process begins. “There needs to be some consequences paid for that type of action [i.e., targeting drinking water sources, intentionally polluting waters, etc.] because it's part of a war crime. Maybe that can prevent these things from happening in the future or have them happen less frequently.”

Moving from crisis resolution to risk anticipation

“When we talk about water-related crises, we, as society, are not really prepared (…) There is a tendency that we are planning more for the emergency," says Tropp. Although we are better prepared to deal with a flood, for example, we still struggle with preventing one. "We need to be smarter when planning rebuilding.”

Some of the measures taken in Cape Town:

🔵 Each resident was allocated a ration of 50 liters of water per day.

🔵 Unnecessary water use was banned for activities such as watering lawns, filling swimming pools, and washing cars.

🔵 In agriculture, water consumption was reduced by 60%, and the “saved” water was redirected to the city.

🔵 The municipality introduced a new pressure system, saving 10% of the city’s required water supply.

🔵 On an individual level, residents contributed in any way they could. Some businesses organized "dirty shirt" contests, where employees competed to see who could wear the same shirt to work for the most consecutive days.

And, as I mentioned at the beginning, the risk isn’t only that we could be overwhelmed by water, but also that we could end up with too little. In January 2018, after three years of declining rainfall, increased water usage in agriculture, and a growing local population, officials in Cape Town, South Africa, announced that the city was three months away from running out of water, in what they called "Day Zero." At that point, they implemented a series of measures aimed at reducing water consumption, which helped avoid the crisis.

Currently, however, Johannesburg, also in South Africa, is facing similar issues. In March 2023, a large part of the city was left without water for 11 days after a pumping station was struck by lightning. Due to drought, climate change, and poor city management, residents continue to have limited or, at times, zero access to water.

“These are not state secrets. These are very well-known challenges, but still we are not able to build these prevention systems. We are responding to the crisis when it happens. And then we forget about it again. It amazes me that the memory is so short,” says Tropp.

For him, the solution is to create a highly resilient urban water supply system. “It’s about a system where you, as a citizen, have access to quality water 24/7 (...) I’d like to see water used more in these circular economies.” He gives the example of plots of land that can serve as flood protection barriers, as well as spaces for urban agriculture and recreation for city residents.

“I think water is typically seen more as a problem than a resource you can actually benefit from. But if you can work with these coordinated measures of finding other uses for water, it can be very beneficial for the economy of the city and also for more employment opportunities, for example.”

How can we get there? By talking more about water, recognizing its value and its precariousness as a resource, cooperating on it, and, as citizens, demanding more from our politicians. “We typically say in the water sector that politicians don't win elections on improved sanitation. Maybe they should.”

Photos by Mihnea Ratte for the Climate Change Summit.