Why do we close our eyes to the facts when we’re told a beautiful story about touring the world on foot, in traditional Romanian sandals?

A few months ago, in a book* I bought at a used book shop, I discovered the story of Dumitru Dan - globetrotter and explorer, born in 1890, in a village near Bacău, “the man who circled the world on foot.” Dan, a Geography student at the Sorbonne at the time, alongside three colleagues and accompanied by the dog Harap, had allegedly left Bucharest in 1910 and circled the world on foot, over the course of several years, in traditional clothing and sandals (Romanian: opinci). All this took place within a competition organized by the French organization Touring Club de France. Throughout their journey from Europe to Africa and from Asia to America, the four performed song and dance shows, their sole source of income. The only one to complete the journey was Dumitru Dan, after his mates died ever more spectacular deaths: one of them overdosed on opium in India, another fell into a ravine in China, and the third died frozen and exhausted in the USA. Dan returned to Romania in 1916, and in 1923, after the end of World War I, “he was handed the prize of 100,000 Francs” offered by Touring Club de France and dubbed “world champion.”

I was sitting there, book in hand, nearly frozen. How had I not heard this story before? It all sounded unreal, almost fairytale-like. So I started looking for more information on this moustachioed, bashful looking man, as his youth photos portray him, known as “the Romanian Phileas Fogg.”

Shortly thereafter, I kind of developed an obsession with the history of this journey. Ample materials have been published on the “explorer in traditional sandals,” who entered the Guinness World Book of Records in the ‘80s, in Historia, Gazeta Sporturilor, Adevărul, România liberă, etc. An animation was made after their journey, even. (Opinci won an award at the Transylvania International Film Festival and was recently screened within the Making Waves: New Romanian Cinema selection in the US.) The Buzău County Museum dedicated a major exhibition to the man (Around the World on Foot - 497 “Opinci”), funded with EU money. Several studies about him have been published in anthologies on explorers, both in Romania, as well as abroad.

Gradually, however, I came to realize that although Dumitru Dan was a fascinating character, who inspired many, the reality behind this Homeric epic was much less spectacular. Largely based on fiction, which Dan himself helped circulate, this narrative has been stoked for decades on end, by teachers, museum curators, and journalists--people who either let themselves be seduced by this fiction, or chose to conceal the truth for the sake of the story. The legend built around Dumitru Dan speaks of our need for heroes and inspirational figures, which sometimes has us close our eyes to the facts.

The journey (as told to us)

We know that Dumitru Dan was born on Bastille Day, on July 14, 1890, in Buhuși--back then, a village near Bacău--, one of the family’s seven children. He graduated from the Commercial High School in Brăila and in 1908 left for Paris, to study Geography at the Sorbonne. The man himself recounts that this is where he put together his globetrotting foursome: Gheorghe Negreanu was a fellow Geography student of Dan’s, while Adrian Pascu and Paul Pîrvu were studying at the Musical Conservatory.

Dan took plenty of notes on his journey around the world, yet never published a diary or memoir. However, during the communist era, while teaching geography in Buzău, he held numerous lectures at schools throughout the country. The chronicle of his journey, as I relate it below, is based on several sources--from transcripts of his lectures to documents made available to me by the organizers of the exhibition Around the World on Foot - 497 “Opinci”.

It all began on the day that Dumitru Dan saw a poster that announced a traveling competition organized by Touring Club de France, with a 100,00-Franc award, the equivalent of some EUR500,000 in today’s currency, in exchange for 100,000km traveled in six years - this was roughly the idea behind the contest. The four young men put their team together and enrolled, alongside 200 other contestants from all over the world. Back in Romania, they spent two years preparing for their grand adventure: they learned foreign languages, trained in various forms of relief, and planned out their itinerary. The rules said they had to wear a pedometer and the only means of transportation they were allowed to use were ships, when crossing from one continent to another. But even when onboard a ship, they still had to put in their mandatory number of steps, which meant a few daily hours of walking on-deck.

Their departure occurred in 1910, on April 1, in Bucharest. Dumitru, Pascu, Pîrvu, and Negreanu set off to Budapest on foot, in traditional outfits, opinci on their feet, wrapped in national flags. They were accompanied by Harap, the folktale-named shepherds’ dog.

Their first major pitstops were Budapest and Vienna, where they held a few folklore shows. Next came Prague, Berlin, and from there on they headed toward Denmark, where the border guards suspected them of being spies and held them under detention for a few hours. In late June 1910, the four reached Sankt Petersburg and two weeks later they were in Moscow, enjoying museums and gilded domes.

“In Moscow, we stocked up real well, with sufficient rations, and then all departed towards the Caucasus, together with our friend Harap,” Dumitru Dan recalls. “We’d sleep in fields, under bridges, in trees, when villages were far apart. But we also had to pay attention to the map and the compass, to avoid getting lost.”

Thus, they crossed Tbilisi (which they reached after seven months and 5,500km), then stopped in Tehran, where the four Romanian youngsters “charmed Persia with folk shows” (the explanation, as provided by GSP: “The secret was that the Persians’ religion did not allow them to play musical instruments, so the Romanians made for a fascinating apparition!”).

Their journey continued through Damascus, Baghdad, down the Euphrates Valley, through the jackal-ridden desert and date palm forests, crossed Jerusalem, Cairo, and Alexandria, descended down the Valley of the Nile and touched Sudan.

“The heat would melt our sandals, we swam through sand, hunger had really caught up with us,” Dan recalls about their itinerary on the East coast of Africa, from Ethiopia to Mozambique. From there, they took a turn to Madagascar and boarded a ship headed for Australia.

Dan, Pascu, Negreanu, Pîrvu, and Harap arrived in Sydney in spring 1911. One year after having left Bucharest, this was the fourth continent they touched down on, after a 26,000km journey on land and across the seas.

In Australia, they became stuck in a savage area, where Dan and Pascu were “kidnapped” by the members of a tribe, who tied them up and took them to their camp. The two managed to make their escape, found their fellow travelers, and began a new route: New Zealand - Papua New Guinea - Singapore - Brunei - The Philippines - Sri Lanka - Bombay, which they reached on July 10, 1911.

According to Dan, the Times of India announced the arrival of the Romanians, “awaited by hundreds of onlookers and sporting association representatives.” Rooms had been booked for them at the Prince of Wales Hotel and they were invited to dinner by a rajah, who wanted to hear their travel stories. That same evening, Pascu died of an opium overdose at the rajah’s palace.

Dan, Pîrvu, Negreanu, and Harap continued their journey, but not before their friend received a “proper Christian burial.”

After crossing India from West to East, they also reached Tenerife, where they boarded to Rio de Janeiro. From here, after a few lectures and highly popular folklore performances, they set out on foot again, through Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile, Lima, Quito, Bogota.

In July 1912, they stopped in San Francisco for just a few hours, long enough to board the ship that took them to Japan. From Japan they left for China and, as they were crossing the Nau Lin Mountains, Negreanu fell to his death, crushed against the cliffs of a ravine.

“I was left with Paul Pîrvu, very downtrodden, saddened by the loss of our companion. We could no longer perform our play The Shepherd, which so many had seen. Pascu with his accordion was gone, as was Negreanu, with his comedic skits and a great dancer alongside us,” Dumitru Dan wrote.

What lay ahead for Dan and Pîrvu, still accompanied by Harap, was an extremely difficult leg of their journey: Eastern Siberia and the Bering Strait.

Over the 1912-1913 winter, they walked over 1,000km through the minus 40 degree centigrade freezing cold, crossed Alaska, and stopped in Vancouver, where they took part in a traditional bear hunt. They descended through Seattle, all the way to California - and from there on to Panama, where they boarded a transatlantic ship to Gibraltar.

The European itinerary followed and, in Paris, Dan and Pîrvu found out they were the only ones left, out of the 200 contestants that had enrolled into the Touring Club de France competition.

They crossed the Atlantic Ocean on board the Aquitaine and reached America once again, in the summer of 1914 - this time in Cleveland and Detroit, where they visited the Ford factories.

As World War One was commencing in Europe, Dan and Pîrvu were holding shows and lectures, meeting state governors, and even got invited to a one day visit to the White House.

Once in Florida, Paul Pîrvu, still affected by having crossed Siberia and Alaska, was forced to abandon the trip. The doctors amputated one of his legs, yet Pîrvu encouraged Dan to continue his journey, but leave Harap with him.

Dan forged ahead on his own and, as he was traveling, found out that Pîrvu had died a few months later, in the spring of 1915.

After a month in Cuba, he set out on foot again, through Haiti, Jamaica, and Venezuela, where he even met the country’s president.

Back in Europe, Dumitru Dan was detained under suspicions of espionage once more, but was eventually released.

He reached Romania on March 26, 1916, with a total of 96,000km under his belt. Because of the war, he lacked 4,000km and was unable to claim the prize offered by the French.

He enrolled in Buzău’s Regiment 8 and after the war, in 1923, Touring Club de France gave him the opportunity to complete his journey. Thus, Dumitru Dan set out on the Belgrade - Zagreb - Switzerland course and arrived in Paris in July 1923, right on his birthday (and the national day of France), still donning his traditional clothes and sandals. That’s when he received the world champion title and the 100,000 Franc prize, whose monetary value had been utterly diminished in the meantime.

Back in Romania, he got a job in social insurance for a while and, after World War II, settled in Buzău and taught geography for a living. He traveled across the country and told students about his tour around the world in opinci. He died on December 4, 1978, and was interred in Buzău.

Ten years ago, British journalist Roger Bunyan, a fan of Dan’s, wrote to then-president Băsescu, to draw his attention to the fact that the explorer’s memory was not properly honored and that his tomb in Buzău is highly unkempt. Several months after receiving this letter, Mayor Boșcodeală posthumously dubbed Dumitru Dan a town honorary citizen. At that time, his grave was also renovated and now “comprises a bust, a pair of opinci and the Globe.”

Grandpa

“I remember Grandpa had two broken, twisted fingers, which he couldn’t move, and some stains, like scars on his face. Obviously, like the curious child I was, this was also my main question, What happened?”

This is what Mona Sîrbescu told me in a recent conversation over Zoom. She is Dumitru Dan’s niece after his mother and a Geology Professor at Central Michigan University nowadays. Sîrbescu specializes in meteors and, for a few years now, after CNN documented one of her discoveries (a meteor that had landed in the garden of a Michigan farmer), she receives rocks from around the world at her office address, to analyze and determine whether or not they come from space.

Born and raised in Beceni, a village in Buzău County, Mona Sîrbescu is a graduate of the Bucharest Faculty of Geology, where she was taught and submitted her undergraduate thesis under the coordination of former Romanian president Emil Constantinescu. She taught at the Geology Department for a short while, right after the 1989 Revolution, then left for the United States, where she completed her PhD and eventually settled.

As I spoke to Mona Sîrbescu, I noticed there was something innocent in the way she talked about Dumitru Dan’s journey, as if fragments of her childhood, somehow left unaltered, had been reactivated: her grandfather’s journeys through the jungle and the desert, his fights with orangutans, images of his road-worn opinci, as well as his tragic tales on Pascu, Pîrvu, and Negreanu.

“I’m sure my choice of job was influenced by Grandpa,” she says. “I grew up during the communist regime and it was inconceivable for me to travel across borders. But since I kept hearing of his Sorbonne studies and travels, I unconsciously longed to study and see the world. I was the family’s only daughter and when my siblings and parents saw I enrolled into Geology studies and I was out doing fieldwork all the time, they started saying, Oh, Mona’s going to end up seeing the whole world, just like Grandpa.”

Although she admits being influenced by ‘Grandpa,’ Sîrbescu says her father was her role model and inculcated her with a passion for science and “exact knowledge.” A survivor of World War II with a stint in the camps of Siberia, the Maths teacher was the complete opposite of her grandfather. “My dad told me all the time: You have to be modest, not talk too much, and not dream of traveling, that’s not going to happen under this regime.”

As for her grandfather, she recalls there was always “something mysterious” about him; very rarely would he open up to his grandchildren. “He was difficult to talk to and, to be honest, I was kind of jealous, because I knew he traveled all across the country, lecturing, and I always asked myself: Why doesn’t he come to my school in Beceni, too? But he never did come to our school.”

A few hours after this conversation, I also received an email from her, with the following ending: “My grandfather’s story, the foreign documents and photos, determined me to read a whole bunch of books--travel books, geography books, etc. It was back then that I started learning all the world’s capitals by heart and sleeping with a world atlas in my bed.”

After out conversation on exploration and meteors, as I was looking for information on the village of Beceni, I accidentally stumbled upon a piece of news from 2015, according to which the Buzău County 112 emergency service had received four telephone calls from people in adjoining villages, among which Beceni, who said they had seen “a light in the sky, followed by a loud noise.” Asked if this had been a meteor, Adrian Sonka, the coordinator of the “Amiral Vasile Urseanu” Astronomic Observatory in Bucharest stated, “Yes, this was a meteor.” Also in Buzău County, in Pleșcoi, a meteor was discovered in 2008, in the yard of a local man; today, it sits at the Cluj-Napoca Museum of Mineralogy.

All this information, entwined with Dumitru Dan’s biography, on which I kept uncovering a growing number of clues that hinted it might not have been as exciting as his own stories belayed, had a weird effect on me--they made me feel that, beyond the discussion on facts versus fiction, certain coincidences exist, which do not easily lend themselves to interpretation. After ‘navigating’ through so many countries and continents, I kept ending up in Buzău, in one way or another, as if I were some conspiracy theorist looking for secret portals and tunnels that connect Pleșcoi to Michigan.In order to avoid completely succumbing to fantasy, however, I decided to take a quick trip to Buzău.

The Dumitru Dan idea

I left Bucharest on a freezing morning with washed-out grey skies and my first stop was at the Buzău County Museum, hidden among ‘80s apartment buildings, in the same edifice as the “George Ciprian” Theater.

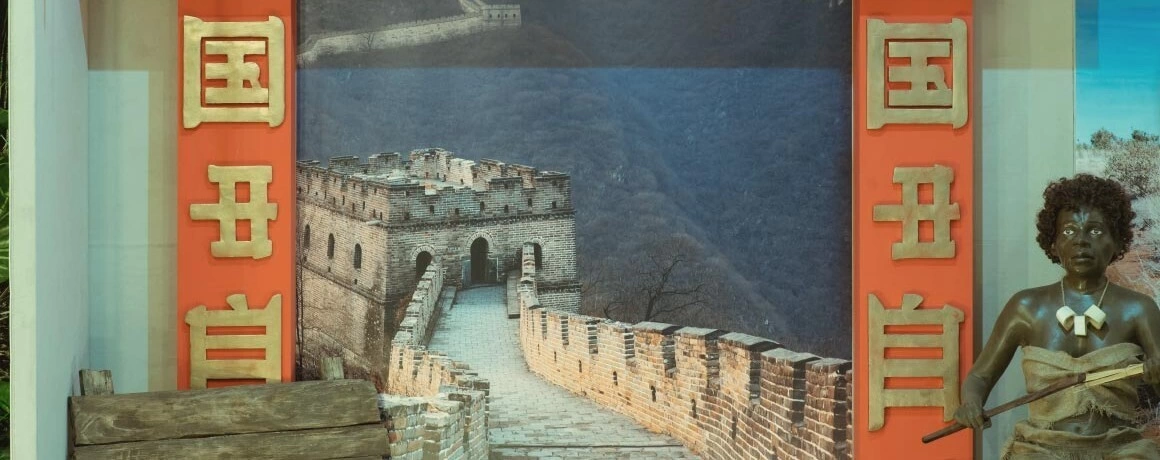

The Around the World on Foot - 497 “Opinci” exhibition is somewhere upstairs, in a room filled with the sound of folklore songs. The exhibition aims to recreate certain scenes in the four Romanians’ journey, with descriptions of their adventures through the jungle, desert, and other remote realms. At the entrance, you are greeted by panels filled with information about the journey around the world, undertaken by Dan, Pascu, Negreanu, and Pîrvu, “which began on April 1, 1910.” There are many pairs of opinci, too, strewn all over the place like bunches of grapes, all of them new and shiny, probably never worn. Along the walls, several displays of photos, newspaper clippings, documents, all of them dating back to 1914-1916.

What’s at once surprising and funny is that these very displays include documents that actually contradict the story Dan told throughout the years and information that is at odds with the main description, on which the exhibition is based. Among them, a clipping from an American newspaper that describes Paul Pîrvu as “the Cleveland-based Romanian that recently joined Dumitru Dan” on his tour across the US--while the official story says Pîrvu had left Romania a few years prior. An article from a Michigan newspaper says Dan is touring the world on foot, in a competition “with a prize of $20,000,” as opposed to the 100,000 Francs in the original version.

Aftering touring the opinci room, I went to the office of the manager, Daniel Costache, who invited me to sit down for a cup of coffee. Costache told me from the get-go that nobody in Buzău had heard of Dumitru Dan before this exhibition. “And, I must admit, we, at the museum, had no clue about him either,” he added, sipping on his coffee.

The idea behind the project emerged some ten years ago, when several Buzău County Museum employees received training in Denmark.

“One of the trainers there, who was also a journalist, told us, Oh, that’s so cool, you’re from Buzău, you’ve got Dumitru Dan there!,” the museum manager recalls. “And the guy was obviously surprised that we’d never heard about him. So, then we decided to look into this. So, the input for the exhibition came from abroad, it didn’t come from us.”

Costache remembers the exhibition’s opening event in 2015 “slayed,” as people were only then discovering Dumitru Dan. Since then, the museum has sought to “sell the Dumitru Dan idea” in various forms, including through associated events, such as the County Cycling Tour, organized in his memory.

“This was the message we kept promoting: Dumitru Dan’s story goes on! And it really does go on!”

Several problems

In late 2019, American ultramarathon runner and blogger Davy Crockett posted episode 42 of his Ultrarunning History podcast, accompanied by an article titled Dumitru Dan - Romanian false globetrotter. It’s a very well documented longread, through which Crockett set out to debunk the whole myth surrounding Dumitru Dan and his journey. The second I came across this text, it completely altered my perspective on Dumitru Dan, especially since none of the Romanian press--not even some foreign publications--had questioned the truthfulness of this “fabulous” journey. The story of Dumitru Dan was cited as is, without a single trace of investigation or analysis. The notable exception is a piece published in Historia (titled The So-Called Trip around the World in ‘Opinci'), published a few years back by Timotei Rad, a young man with a vast experience of hitchhiking around the world. Just like Crockett, only in a more impassioned tone, Rad dedicated a lot of his time to this text, which meticulously dismantles Dumitru Dan’s journey through the use of distance measurements, as well as archival material.

The conclusion Crocket reaches is devastating: nearly the entire story of Dumitru Dan and the trip around the world in opinci is, in fact, one big hoax. The only trips we know for a fact that he took were those in Europe, North American, Cuba, and Venezuela, where there is proof to attest he visited between 1914 and 1916.

I tried to understand how the myth around Dumitru Dan was born. If you move past the instant fascination caused by discovering this character, even in the absence of geographic knowledge, there are several things that stick out when you read the description of this spectacular journey. Let’s take them one by one.

All signs point to the fact that Touring Club, the organization that Dumitru Dan claimed organized the globetrotting competition with an award of 100,000 Francs, never held such a contest.

Founded in 1890 by a group of cyclists, the Touring Club de France Association (TCF) aimed to promote tourism, cycling, motorcycling, and winter sports, and never targeted globetrotting competitions or events. No presentation on the (rich and well documented) history of the TCF includes any reference to such a competition or any one of the four Romanians--this while such a tour around the world would have been by far the most important event organized by the French association throughout its century-long history. It would’ve certainly garnered a lot of press attention; yet it doesn’t feature in any archive. Not even Gallica, which hosts the entire backlog of the Touring Club de France Magazine and has a thorough search engine, can provide any mention of the 1919-1916 competition, our fellow Romanians (I didn’t search for Harap, I’ll give you that), or a prize awarded to Dumitru Dan in 1923.

Crockett explains that it’s highly likely that Dumitru Dan wound up inventing the TCF story, since, in the early 20th century “hundreds of people were claiming falsely that they were walking around the world and were given free room and board.” Among them, names such as F. Consigny, Gustave Laurent, Henry V Mosse--young Frenchmen claiming to be taking part in competitions organized by Touring Club de France around the world, which never took place. There’s a pattern of imposture in these three cases, too: these men usually traveled alone and only to a handful of countries (among which the USA), but claimed to have been on the road for years. Their stories were improbable, just as the distances they had allegedly travelled, and their testimonies kept changing permanently and were imbued with drama, at a time when verifying the accuracy of such information was a very difficult task to accomplish.

And these things were happening around 1904-1905, a few years before the four Romanians’ alleged journey took place. Dumitru Dan wouldn’t have had anything else to do but take over a ‘fashionable’ scenario.

Historian Andy Milroy, who also writes for ultrarunninghistory.com, believes that, “after they start out with naive and unrealistic projections,” such travelers gradually end up self-sabotaging and taking “shortcuts (...) In my experience, they generally wind up believing their own claims. They become enmeshed in their own fiction.”

In his interviews with European and American newspapers, during the travels he actually undertook, Dumitru Dan contradicts his own claims on many counts.

For instance, at a certain point he tells some American journalists that he’s competing for a $20,000 prize awarded by the Romanian Sporting Society, as one of the articles on display at the Buzău County Museum shows. At other times, he mentions nothing about the TCF to the journalists he talks to. In fact, as Davy Crockett notes, Dumitru Dan’s story is ever-changing, both in terms of timeline, as well as in what concerns the distances and routes he’s traveled. This is clearly illustrated by the 1914-1916 documents and newspaper clippings. In one interview he claims, among other things, that he took part in the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars--which took place at the very same time that he was allegedly crossing Alaska and Canada.

Another highly problematic aspect is that regarding the distances and number of kilometers that Dumitru Dan claims to have traveled.

In a 1975 interview for Silviu Neguț, a Geography professor at the University of Bucharest and the man who fought to have the “world tour in opinci” featured in the World Book of Records, Dumitru Dan says that he and his companions walked for “45 km per day (and even more).” The claim is absurd and, as both Crockett and Rad, experienced travelers themselves, note, such a pace is impossible to maintain for longer spans of time, all the more so when you travel under difficult conditions, through the desert, the jungle, or Siberia, especially in traditional sandals. In the same interview, Dan says that, once he “arrived at the Touring Club de France, [he] presented the statistics of the 100,000 km traveled: 89,000 km on land and 11,000 km on water.” What’s surprising is that Neguț, a geography expert and textbook author, does not challenge such a statement at all. 11,000 km on water in six years is an unlikely number, considering that the distance between Madagascar and Australia, a leg of DD’s journey, totals nearly 9,000 km on water. And this without even taking into account the numerous travels by sea they allegedly undertook throughout those years.

Now we arrive at the famous opinci, which everyone mentions when Dumitru Dan comes up and which provide both the title of the Buzău exhibition, as well as that of the 2019 animation short. According to Dan, the four travel companions tore 497 pairs of opinci during their journey - their relatives in Romania would provide them with new pairs, as well as with traditional clothing, as they went along with their itinerary. Dumitru Dan is also the one to inform us that the globetrotting group was made up of young men of modest heritage. The question arises: how could some Romanian peasant families send hundreds of pairs of opinci (and in 1910, no less) to various places around the world, from Australia to East Africa and Northern Alaska?

There are no documents attesting to the first years of the journey recounted by Dumitru Dan.

The documents behind all the articles about Dumitru Dan, which also accompany the exhibition at the Buzău Museum, are as real as they get - show posters, newspaper clippings, tickets, postcards, the stamps of various institutions. But the archive only covers the 1914-1916 period and only deals with Western Europe, the USA, and Cuba. Nothing from Australia, Africa, India, Iran or Syria, Japan or China, and this even as DD loved collecting souvenirs along the way, especially when they proved his presence in certain places. Mădălina Oprea, head of the history department at the Buzău County Museum and author of several articles on DD, admits that she, too, was unable to find documents outside the 1914-1916 period, even after digging through archives both in Romania and abroad. Professor Silviu Neguț’ explanation is that the “gigantic archival material on the extraordinary journey was either lost or requisitioned, or scattered to the four corners of the world.” It’s strange, though, how all papers from 1910 to 1914 were lost, while a whole archive popped up afterwards.

Pîrvu moved to Minnesota after he died.

If Neguț & co had analyzed the documents in question more carefully, they would have come across another fascinating aspect that Davy Crockett did notice: Paul Pîrvu, of whom the official version tells us he allegedly left Romania with DD in 1910 and died of exhaustion and frostbites, is presented in the American press of that era as a Romanian from Cleveland, Ohio, who joined Dumitru Dan on his US tour in 1914. This means Pîrvu only met Dan in America and traveled with him for a few months to several American cities, to which they walked very little, as Crockett also concludes. As for Pîrvu’s death, it also belongs to the same fictional scenario. In reality, after a few months of traveling, Pîrvu returned to Cleveland safe and sound, fought in World War I, then moved to Minnesota, where he died in 1938, as ancestry.com also informs us.

When I brought up the controversies surrounding Dumitru Dan in the conversation with Mona Sîrbescu, the niece of the storytelling globetrotter, she told me she is aware of the existence of certain disputes, but hasn’t closely looked into them. “And my memories aren’t the most precise either, not to mention I was young at the time, I was 13 when Grandpa died. But, to be honest, there is one thing I do remember and which made me think, even as a child. I remember a family conversation in which they were saying that Pîrvu, whom they alleged had died in America, was actually alive after Grandpa had returned from his voyage. I thought that was strange.

Yet one question remains: what happened to Pascu and Negreanu, the other two travel companions? The most plausible scenario is that Dumitru Dan also met the two later on, in America, in the same Romanian community which enabled him to meet Pîrvu.

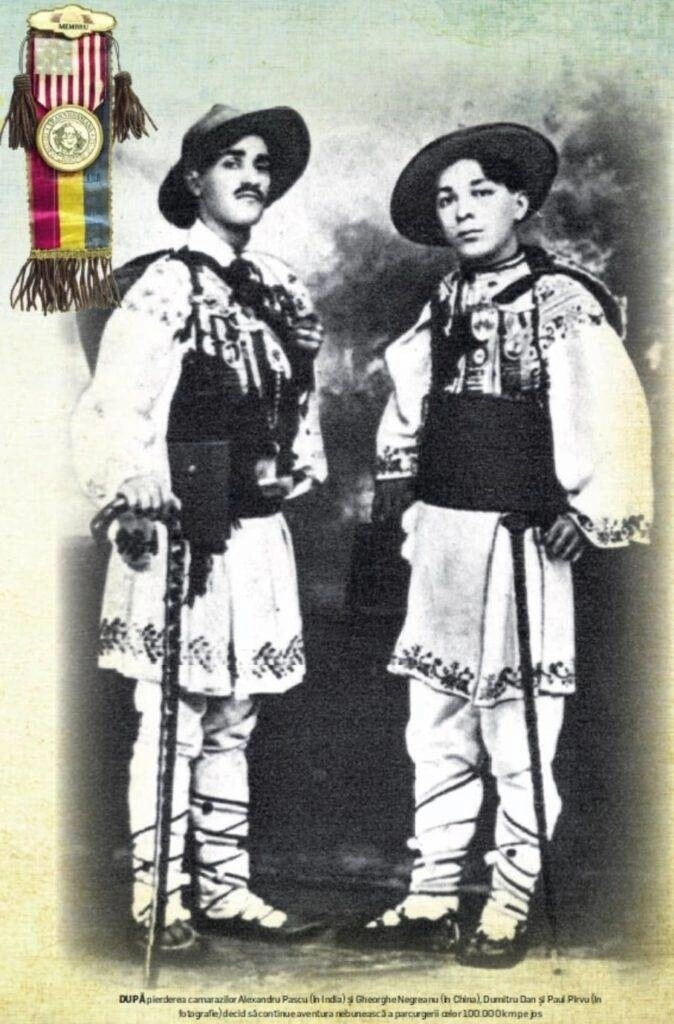

There’s an iconic photograph of the four young travelers in traditional outfits, next to a dog - the only photo in which they appear in this formula. Among them, we recognize Dumitru Dan, who, aside from here, appears alone in his photos in Europe. The photo of the four does not represent proof of their journey around the world. It might as well have been taken at one of their American performances, together with the Romanians who had settled there. Whether or not their names are Pascu and Negreanu remains a mystery.

We do know for a fact that a certain Alexander Pascu left Bucharest and reached America in 1903, aboard the ship La Champagne, as the Ellis Island Foundation archives show. This was six years before the supposed trip around the world. According to ancestry.com, Alexander Pascu died in 1933 in New York, two decades later after that opium overdose in the palace of the rajah whom DD claimed had taken out his expedition companion.

Then, there’s Harap the dog. Here, the situation is pretty clear and, as Crockett also states, it’s impossible for a dog to have traveled by his side for tens of thousands of kilometers, throughout the course of five years. “The dog is never mentioned by the American newspapers” and would have never been allowed on board the ships, especially seeing as the rules on animal access to the territory of certain states were very strict and stipulated that they be quarantined or seized by the authorities. The conclusion: unfortunately, Harap is nothing more than a fairytale dog.

The expert’s opinion: “There’s this temptation to exaggerate”

I discussed some of these things with professor and geographer Silviu Neguț, considered an expert on this topic, about which he’s written several articles and studies. Born in Buzău County, Neguț had heard of Dumitru Dan in his childhood and had always regarded him as a hero. He personally met him later, in the ‘70s and, despite the age difference, they became friends. Neguț invited DD to hold several presentations at the Faculty of Geography in Bucharest. One thing that made Neguț sad even back then was that Dan’s financial situation was poor and his pension was “peanuts.”

“I skimmed the American guy’s thing, gave it a look-over,” the professor commented on Davy Crockett’s article over the phone with me. “All I can say is that Dumitru Dan was a highly organized man, whose will was out of the ordinary. And he was a warm person. He opened up like a flower if he saw you were interested in him. I doubt that this man would’ve been able to lie to such an extent.”

However, Silviu Neguț admits that he, too, had his doubts, ever since Dan first mentioned that “daily 45-kilometer average (...) It struck me as something very hard to achieve. And I have to say I was most intrigued by that thing about China. Dumitru Dan said that Negreanu, his travel companion, died in China, as they were crossing some mountains. Except, in other contexts, he said Negreanu had eaten something gone bad and that’s what had led to his death. But I’ll have you know I’ve met lots of travelers and explorers and explorers, even world-class ones, and I noticed there’s this temptation to exaggerate.”

Yet these doubts didn’t alter Neguț’s perspective on the fabulous trip around the world. What’s more, ten years ago, he actually dedicated a one-hour episode of a show he used to produce for the National Radio Station to DD. “When you’re on the radio and you know you’re talking to a very wide range of people, it’s best not to raise concerns and mention such disputes,” says the geography professor. “You have to present the positive things and aspects, so that people are proud to have had such a fellow Romanian.”

A few minutes after we concluded our conversation, Silviu Neguț called me back to warn me about something. “If you decide to write on other such topics, in the future you might be contacted by two people, two women, who will claim they’re explorers and have traveled to this and to that place. In case that happens, you should know those two are impostors. I can give you their names, if you’d like…”

Maybe to Australia

From the County Museum, which tells the glorious tale of the “journey around the world,” I went to Beceni, a village 30-kilometers away from Buzău, down the road that runs parallel to the Slănic River valley. Long ago, this pothole-filled county road was a trade route for “salt, wood, and sheep,” which connected the plains to the mountainside. Beceni is in a hilly area, in the midst of a leafy forest, not far from the Muddy Volcanoes.

Dan and Florin Sîrbescu, Mona’s brothers and the nephews of Dumitru Dan, live in the old family home, on the main road. By the gate hangs an old sign, which says, in red lettering, Computer repairs.

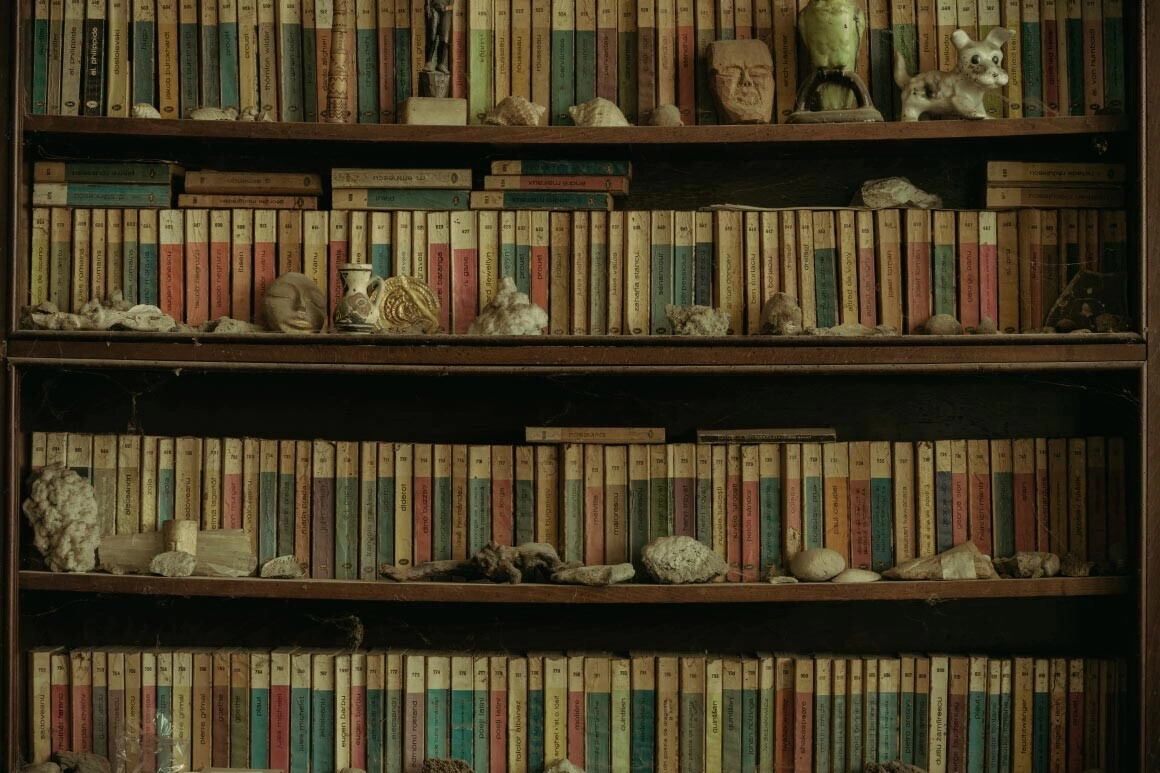

The house is old and in pretty bad shape, but very roomy. You walk right into a large room with a tall ceiling, filled with books, old paintings, porcelain figurines. There’s also a bookcase frozen in time, with a lot of books from the BPT collection, the kind in which you would definitely find The Shogun and The French Lieutenant’s Woman. However, it’s terribly cold, so we move to a small room with a stove, where Dan types on the keyboard of his old PC.

Dan, a very soft spoken man, with Santa’s smile and beard, is born in ‘55 and is Florin’s senior by six years. Mona Sîrbescu, who left for America in the ‘90s, is the youngest of them all. Dan is a Constructions Faculty graduate and worked as an engineer for Rotec Buzău, from where he was laid off.

“I thought I’d start a small computer repair business,” he says, looking at the screen that runs rows of numbers and calculations. “Except nobody came by for me to fix their computer.”

After the 1977 earthquake damaged his house, Dumitru Dan also moved to Beceni, which is how the nephews got to spend more time with him. Only ‘Grandpa,’ accustomed to city life, never adapted to life out there and moved back to Buzău after a while, in a studio on Lenin Avenue.

“Grandpa used to tell us about his travels, too; basically, he’d practice with us before his lectures,” recalls Florin, leaning against the door frame, cigarette in hand.

“He was a cheerful guy, talked to everyone, and was restless,” Dan adds. “He never took the bus in the city, he’d only walk around Buzău.”

They’re both men of few words and steer clear of providing details, but it’s enough for me to realize that their memories are different from Mona’s. The ‘Grandpa’ in their stories is more open and jovial, probably also because, as they were older, they got to spend more time with him.

It’s gotten dark outside and one of the three cats, the white one, spotted black and orange, whom they call Half Tail, has jumped onto the bed, among the duvets, and is about to fall asleep.

“So, didn’t all those stories Grandpa told make you want to travel, too?” I ask them.

“I would’ve liked to travel, but couldn’t because of the regime,” Dan answers with a melancholy smile. “And after ‘90, I was too old to go anywhere.”

Florin takes a drag from his cigarette and doesn’t say anything.

“So you’ve never traveled abroad?”

“No, never. Our sister’s the only one who’s traveled a bit…”

“So, if you were to go abroad now, where would you go?”

Florin starts laughing and stares me dead in the eyes.

“I don’t know… anywhere… Maybe to Australia.”

“Why Australia?”

„Nu știu... poate pentru că nu am fost niciodată?!”

Florin suggests we go back to the cold living-room, to browse the collection of postcards and photographs their grandfather left them, many of them a century old. As Florin takes out the small archive, I ask Dan what he thinks of the articles that dispute his grandfather’s achievements. “Yeah, I know about that, I actually had a debate about it online with an American,” he says. “Some guy wrote something about how he couldn’t have made that trip.” I’m assuming it’s Davy Crockett, but don’t manage to find out more, because Dan quickly closes the subject. “My discussion with the American was left off… hanging. He’s got his truth, I have mine.”

In front of us, on the table, several dozen postcards, photos, and old documents are scattered: they’re postcards and letters Dumitru Dan received throughout the years, from people he met in various places that he actually did travel to, from Los Angeles to Băile Govora, as well as some which he sent his relatives here, from the time he traveled across Portugal, Italy, etc.

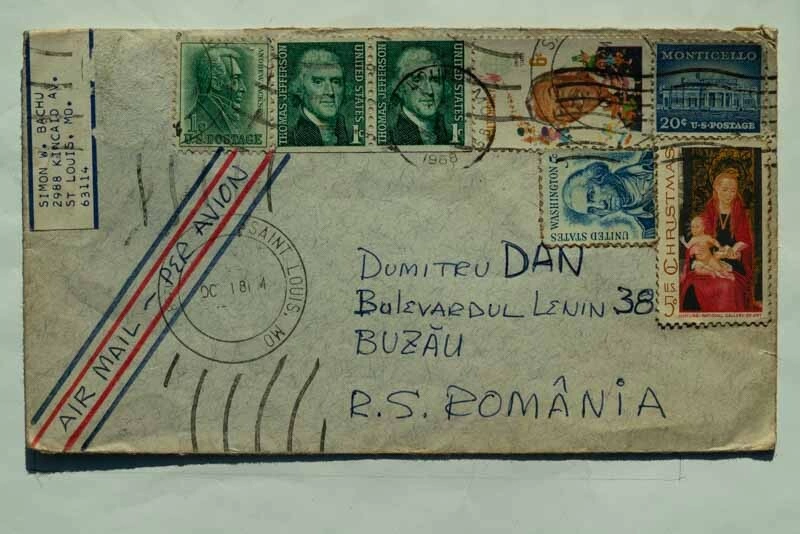

Some of the envelopes received on his address, including during the communist era, list “Dumitru Dan, Geography Teacher, Former and Current World Champion of walking around the world,” “World champion,” “World champion at 100,000 km on foot,” etc.

It’s obvious that Dan made a lot of friends during his travels, as Mona Sîrbescu confirms, while she remembers how “Grandpa would always be writing and receiving letters.” At the same time, what strikes me is that this archive doesn’t contain any postcard or document connected to those first few years of traveling, when he was allegedly ambling up and down the Globe. And it’s no coincidence that those writing to Dan only hail from Western Europe, Canada, and America. That is, the places Dan actually went to.

Still, I get emotional when I see all these cards weathered by time lined up on the table, under the nephews’ eyes: images of Venetian canals and parks in Rotterdam from the early 20th century, sights of monuments and landscapes in Montreal, New York, and Brăila, sometimes accompanied by thoughts for his sister and parents in Buhuși, which Dan signs as “Mitică.” Several worlds overlap here: the chaotic and intense years of World War I, when everything is about to change, the interwar era, when Dumitru Dan undertakes a few more trips through a Europe that’s been turned upside down and complains how badly his business is doing, followed by the communist era, with its sunny postcards, full of new highrise buildings and shiny Dacia cars, when Dumitru Dan’s life is narrowed down to Buzău’s Lenin Avenue.

Yet what most captures my attention is the 1914 documents, from the time when Dan and Pîrvu were performing shows in various American cities. Dumitru Dan had also made friends among the Romanians who had settled there and it seems many of them kept fond memories of him. As I browse these postcards, I find one dated January 1915, sent from New York by someone signing as W. Sass to Dumitru Dan, from a Washington address:

Honorable Mr. Dann,

we are glad you arrived in good health and are still alive, as Mr Pîrvu told and even wrote to many that your death is the cause of his return and I am put in difficulty by several persons but today I will prove to them that you are still alive at present. They have all already said may he rest in peace and we had such a laugh over it. Our compliments. Bravely onwards.

I must’ve read these lines about five times and I still couldn’t get over the daze they put me in. It didn’t surprise me that Pîrvu, whom glorious history had recorded as having died of frostbites, was still alive, as many clues already pointed in that direction--but that Pîrvu, in his turn, had spread the same fake rumor among his acquaintances, of his travel companion’s demise. I burst into laughter right then and there and, at the same time, realized that instead of clearing up my unclarities, this information only had me facing other complicated questions and leads.

En route to Bucharest that evening, I also stopped in Buzău, on 1 December Avenue (formerly Lenin Avenue). I wasn’t looking to find something in particular there, I didn’t even manage to spot the building where Dumitru Dan had lived. I walked down that dark, deserted street that runs parallel to the railroad tracks, until I reached the station, outside which there’s an old time Malaxa train engine.

EPILOGUE

End of February. I’m at home on the couch, perusing Valentin Borda’s book, Romanian Travelers and Explorers, where I first came across Dumitru Dan’s story, in December 2020. It’s designed as a dictionary and, a few pages after Dumitru Dan, also under the letter D, there’s a chapter dedicated to Constantin Dumbravă, glaciologist and polar explorer. Dumbravă, who settled in New York in the ‘20s, took part in and actually led some expeditions to the Arctic (among which the first Romanian expedition to Greenland), under the auspices of several French and American scientific societies. He died in Cannes, aged 45. But what really catches my eye is his date and place of birth: April 15, 1890, Buhuși, Bacău County.

Constantin Dumbravă was born in the same year and village as Dumitru Dan.

I also asked Silviu Neguț what he knew about this story and whether he ever talked to DD about Dumbravă. “Yes,” Neguț replied. “Dumitru Dan told me he’d met Constantin Dumbravă at an event in Romania. They met, but didn’t talk too much.”

* "Romanian Travelers and Explorers" (written by Valentin Borda and published by the Sport-Turism Publishing House in 1985)

Translated from the Romanian by Ioana Pelehatăi.