She’s a contemporary artist, a teacher at the Photo-Video department of UNARTE, and co-curator of Salonului de proiecte in Bucharest. In 2014, Alexandra Croitoru got her PhD degree with a thesis on the “nationalization” of Brâncuși in Romania. In 2015, she published Brâncuși. O Viață Veșnică (Brâncuși. An Afterlife), an excellent analysis on the usage of the name and face of Brâncuși in various contexts, both underground (MISA), and official (country strategies). “Brâncuși. O Viață Veșnică” (“Brâncuși. An Afterlife”) is an essay that helps us understand the history behind “Brâncuși is Yours”, the origins of the cult and where it is heading. I talked to Alexandra on one of the last days of summer, in the garden at Green. We laughed a lot, which is quite surprising, considering that lately this subject has given birth to heated debates. As always, putting some distance between oneself and the subject always helps.

Why made you pause at Brâncuși? He wasn’t just the subject your PhD degree, but of a series of art pieces that spanned many years.

In the ‘00s, I produced several pieces that questioned the concept of national identity: what it means, how it functions, what the border between reality and fiction is. This is what ignited my interest. The first Brâncuși episode was in 2009, when Ștefan Tiron and I applied for the Venice Biennale with a project called “Moștenirea lui Brâncuși” (“Brâncuși’s Legacy”). It discussed the condition of a national artist and how it could be contextualized in Venice, the place where art was rumored to have national tendencies; that each country goes there and showcases its best and most representative work and people. It was a fun project. The content was written in such a manner that if you refused the project, you were rejecting Brâncuși himself, not just us. It was quite successful, from what I understood from the people in the jury, but it wasn’t enough to get us to win. We said to ourselves that we would apply every single year, until the authorities realized the importance of the project. (She laughs) We didn’t do it, but maybe we will…

So that was the starting point.

Yes, it was linked to nationalism and what it means to be a national artist. The interest in Brâncuși was what followed. In 2010, when I started the PhD at UNARTE, I thought it was a good subject to research for 3-4 years of my life. It was large, juicy, and in a way funny. Ultimately, that also mattered, the fact that it wasn’t divorced from everyday life.

Tell me a bit about the cult of Brâncuși pieces that you worked on while you were researching your PhD.

Maybe I should first mention that the PhD was a so-called vocational one, or an artistic research, as it is being referred to in an international context. It’s not exactly clear what that means and how work can be evaluated, but we were given plenty of flexibility and our teachers agreed to take into consideration our artistic contributions, which in itself was a massive achievement. Because the micro-system permitted, there are several of us who developed both text and artistic work. What followed was me putting together exhibitions on this theme, while I also was working on the book Brâncuși. O Viață Veșnică (Brâncuși. An Afterlife).

The pieces I created during my research years had many sources of inspiration, and many starting points. One was Mr. Laurian Stănchescu and the crusade for the repatriation of Brâncuși’s remains. Other pieces were born while I was in Paris, living in a place that was coincidentally called Brâncuși. It was there that I had contact with the Atelier Brâncuși, with his tomb in the Montparnasse cemetery, another trigger for me. What actually came to life on this theme is very diverse, from an object or performance, to video and text. It’s a topic that allows visual play. There was also the piece on the Brâncuși cane that I did together with Napoleon Tiron, which started from a discussion on Brâncuși and Romanian sculpture. I believe that many sculptors grew up with the idea that Brâncuși was the ultimate sculptor. It was almost blasphemous to dare question this in any way. Many people perceive my work, the text or the interventions that I do, as criticism aimed at Brâncuși. I’ve lost years of my life trying to explain that it has nothing to do with the man himself, but with people’s perception of him. He’s dead, he hasn’t approved of anything that happened after he died. I find it unbelievable that art-educated people can’t tell the difference between Brâncuși, the man, his work and how it is being used in the public discourse in Romania.

Aside from the art pieces on the cult of Brâncuși, last year, I did two exhibitions on the same theme. The first episode of „Fiii și fiicele lui Brâncuși” (“The Sons and Daughters of Brâncuși”) was Salonul de proiecte’s contribution to Timișoara Art Encounters. It was surreal. I didn’t want to make an exhibition where we would hang things on walls, so the first episode was centered on workshops open to the public. And in Cluj, at Plan B, we conceived an exhibition that was more of a documentary than an art display, featuring plenty of artists who had been interested in Brâncuși. In Timișoara, at the gallery of the Fine Artists Association from Romania, we would have workshops there every single weekend, on the city’s main street. We were aliens to those people, and we were being perceived with hostility because we were taking over their ground. Before Brâncuși became a controversial topic, there was a certain degree of aversion towards Bucharest artists who came to colonize the Fine Artists Association in Timișoara. Every weekend, all types of characters came there and it would always descend into heated arguments and fights. At one point, a lady even punched one of our collaborators. We called the police.

She hit him because of Brâncuși?

It was because of a discussion on political art, but I don’t remember exactly. What I do remember is that at one point, the lady simply cracked. I realized how fragile people are. In a way, that’s quite endearing, that art can still make one’s blood boil, and that it’s not a subject people are jaded about. But I believe the public perception of Brâncuși cannot really change in

In a text from Dilema, you said that the esthetic perception of Brâncuși is no longer possible at this point.

That’s what I believe. At this very moment, if you’re inquiring about Brâncuși, it’s because of the media circus that’s been going on. I find it a bit over the top and people are starting to react negatively to this.

A few days ago, journalist Teodor Tiță wrote on Facebook that he donated to the campaign and now felt like asking for his money back…

Yes, the campaign is too large for a mere sculpture, and this creates an unbalance. And let’s not forget that considering all the efforts made for this campaign, not much money has been collected. This is funny and sad, at the same time.

Have you donated?

No, but I will. Not because I’m trying to wash my sins away, simply because I have no sins, but because so many people strongly believe that I have something against Brâncuși. So, I think this is a good opportunity to show them that out of my meager artist earnings, I will donate. I will donate half of the fee that I received from MNAR when I did the exhibition “Aceasta nu este o piatră” (“This is not a stone”). The payment was a big surprise to me, simply because MNAR doesn’t work with living artists. It’s a touchy subject and many ask “Why should we pay so much money for a sculpture when there are contemporary artists who aren’t being funded?” But in the end, it did happen. I think that exhibition caused an internal revolution for MNAR.

The campaign will end around the time of the elections and I think everyone will start thinking about how this failure will be perceived by the public. What do the politicians think? I am very curious to see how this will be exploited.

A modern nation was also built by writers, poets, musicians, and artists, through the stories they created and this remains valid to this day. When it comes to a sculpture alone, you won’t be getting 6 million euros, but with the whole discourse of “Brâncuși is also yours, just as this country is”, you might stand a change. People don’t want the Wisdom of the Earth because it’s an interesting piece of art, but because it was made by a Romanian, by the “world’s biggest sculptor”, who was from village of Hobița and so on and so forth.

Should the Wisdom of the Earth stay in Romania?

No, I don’t think it’s essential for it to be in Romania. But I do think it is important that they tried to get it to stay, that they didn’t give up easily. After all, it is a very valuable piece of art. If you want it, you try to get it. If that doesn’t work, you just go wherever it is and see it there. The only issue here is that if a private collector buys it, it may not be available to the general public anymore. Officially, it’s not allowed to leave the country, but a collector can buy it and you could potentially never see it again. I don’t think there’s a law in Romania that forces collectors to publicly exhibit their art collections. That would be the only danger, not it going to another country. This touches upon that nationalist idea that “the foreigners are stealing the country from us”. The collective imaginarium goes into overdrive when it comes to the threat posed by foreigners, but in this particular case, it’s about the public versus private binary.

What archives did you have access to while doing your research?

Firstly, the Kandinsky Library in Pompidou, which you can only use if you’re a professional and you’ve got a subject you need to study there. I was lucky to have resided in Paris at the time, because I had access to the archives and time to put my ideas in order. Also, because in Romanian libraries, you can’t really find anything on art and critical theory. It’s tragic, the books you can find at BCU; and all book there are so dated. The mere fact that you can access good libraries and you can go about your business is a great advantage and privilege. Besides, I’ve also collaborated with people who had been doing research on this subject: Vlad Nancă, Dan Perjovschi, and many more. Actually, everyone who knew what I was researching was sending me whatever they could find in the media.

“From 1926 until now, the number of Brâncuși quotes, grew from the initial 13, to 120 in Pravila lui Brâncuși (Brâncuși’s Law), to 254 in Zărnescu’s volume, to 274 in Ștefan Stăiculescu’s, and to 550 in Sorana Georgescu-Gorjan’s book.” (from Brâncuși. O Viață Veșnică (Brâncuși. An Afterlife), by Alexandra Croitoru),”

Did you find anything surprising while you were researching the subject?

For me, the most interesting thing was to see how things just came together. They didn’t happen all at once, no. They started on an ascending trend even from when Brâncuși was still alive. I’m referring to the perception of him in Romania and how it had something to do with a type of inferiority complex.

You were seeing that he became cult-worthy only after he received outside validation.

Yes, and after you go through all the bibliography, you see that things suddenly make a lot of sense and that it was only natural for things to head into this direction. There is this legend that he wanted to leave everything to Romania, but the Romanians refused, and I find it quite interesting. There is no proof of this, but you can’t convince anyone that it is just a legend. A minor article by Barbu Brezianu, who used to be a highly respected brâncușiologist, gave birth to an absolute truth, even though there is no research done on this. I’ve read several texts written by dignitaries, people from the 60s political scene which reveal that Brâncuși was not seen as an enemy of Romania. I believe that things are highly nuanced. But, because we still have the need to vehemently deny the communist past, people aren’t ready to nuance. Not yet, anyway. Maybe they will, in a future not too far away. Brâncuși even popped up in Sighet, at „Maeștri după gratii” (“Maestros Behind Bars”). What was sown at the beginning of the 90s, grew roots in the national consciousness as an indisputable truth.

What are the main stages of the manner in which Brâncuși is perceived in Romania? And at what point did this perception steer over into cult territory?

At first, when Brâncuși was still alive, the avant-garde in Romania wanted to be connected to him, because he was a renowned international artist. But then the war came and Brâncuși was no longer a hot topic. Then there were the 50’s, when the decision-making apparatus focused the attention on socialist realism. The focus simply fell on different things, but this doesn’t mean that there weren’t any Brâncuși exhibitions. A year before his death in 56, there was one in Craiova and one in Bucharest. Thus, he wasn’t completely invisible on the Romanian art scene.

This interest in Brâncuși was also manifested through the confiscation of Wisdom of the Earth.

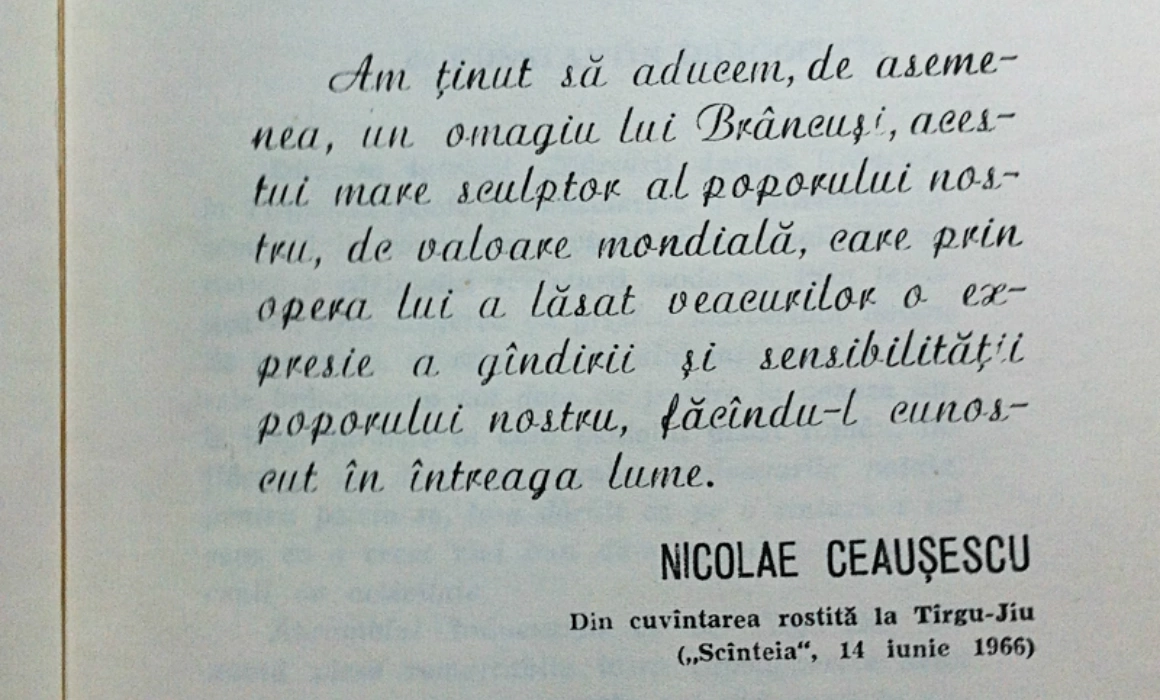

Of course, back then they took whatever they could. And so it started… The first homage symposium took place in ’67 and it was then that the mythologization process of Brâncuși began. It ended up getting caught in the protochronism story and steered into the popular area, with traditions and folklore. On the other hand, in the 60s, some Romanian critics were reacting to Sidney Geist, an American critic and fan of Brâncuși, as he was judging him according to some “universal” art history criteria. They were all trying to dismantle his theory and show that Brâncuși was a Romanian and what he was doing was to continue a certain local tradition. Even Eliade supported this populist tendency in a way. There were some theories that connected the work of Brâncuși to the substance of the Romanian people. But things were a bit more complicated than that. For example, Eliade was saying that this ancestral local element met with archaic universal ones.

There was also plenty of literature that opposed Sidney Geist, which sparked the idea that Brâncuși and the Romanian spirituality were interconnected.

So the cult has its roots in communism?

Yes, at least the one we’re experiencing right now. And it’s tied in with protochronism. Brâncuși is a national treasure, a pioneer, the “inventor of modern sculpture” – these are the words that are still being used today. But does it mean, to be the inventor of modern sculpture?

If someone wanted to see who Brâncuși really was and what his artistic motivations were, where could they turn?

From what I’ve read, Brâncuși was a person who cultivated a certain degree of mystery about himself. He didn’t use to talk about his pieces, he didn’t explain things. He was a highly charismatic character, who always welcomed that mystery about him, which lead to so many interpretations of him.

For his work, one must see his Paris atelier. There are plenty of pieces that can be seen in museums across America. I recommend direct contact with his work, and as much as possible, to avoid Romanian literature. There are very few texts that don’t discuss his work from a nationalist perspective.

Barbu Brezianu put out a raisonné catalogue with all of Brâncuși’s pieces from Romania, with many details for each piece. It is very technical, which is a good thing, because it doesn’t leave any room for interpretation. I also find the DVD that Centre Pompidou put out a few years ago very interesting. There was an exhibit with Brâncuși’s photographs and the clips were on that DVD. It’s wonderful to see them, because you get to see the character. It’s well worth it. Otherwise, in Romania, it’s hard to avoid the exacerbated and populist tendencies.

In your book, you speak quite lot about appropriation. What does it mean, exactly? You give Western examples, such as Miró and Wagner. Does a central culture appropriate differently from a marginal culture, such as our own?

The mechanism is the same, everywhere you look. At certain times in history, cultures need to justify, engulf, annex, and appropriate entities that would benefit them in terms of public image. It’s a mechanism that works both in business and in national communication. It’s the same reason why our country’s branding uses the image of Brâncuși. National advertising has its origins in strategies that were initially used commercially. I used the word appropriation only because my mind works in symmetries. The idea that artists appropriate elements from the social area, from their everyday life, is absolutely fine. Because they can do it critically or they can use those elements to create a whole different discourse. But there are situations, where the exact opposite happens, when an artist or an artwork are appropriated by a society, broadly speaking. I felt that such was the case of Brâncuși, and that the word appropriation illustrated this very symmetry.

But is this type of appropriation fair? On one side, artists are a minority who can fight against the consumerist society and which why they’re appropriating elements from it. On the other side, is it fair when an entire society or nation appropriates an artist? The artist is dead, they don’t have a say in this.

Still, if an artist is such a significant part of a nation’s consciousness, one just can’t deny the benefits. This has been happening since the dawn of time, these transfers from the domains of art and the world, in general. Then, there also this: many consider that it is just a very unfortunate event that such an important and historical artist ends up in a very populist discourse. But we don’t want art to only be for the elites, do we? For the extremely educated people, who go to Pompidou, and they’re only allowed to talk about Brâncuși there and only there. And in the books, and in the everyday life, you can find arguments for both sides: that Brâncuși must remain in the art world, or that he can escape and may be used by everybody. I don’t think art is only for the elites, but I don’t believe that art can justify embarrassing nationalist actions, either. He can be ours, everybody can use him, but for what purposes?

One of the chapters in your book is about renowned brâncușiologists. Are you a brâncușiologist?

Unfortunately, I believe I am. (She laughs) I am the on-duty brâncușiologist, the young one with a sense of humor. Lately, every time Brâncuși has been the subject of radio shows, they invited me in their studio. I’ve had a good relationship with some brâncușiologists and I find it interesting that people from a different generation can understand things the way I do. For example, take Mrs. Sorana Georgescu-Gorjan. Her father was the engineer who poured the concrete for the Column. She later became a brâncușiologist, wrote books, articles, and even has an archive of photographs from when the Column was erected. I’ve reached out to her a long time ago, I went to her house where she showed me everything she had on Brâncuși and we’ve met on various other occasions. She even came to “Fiii și fiicele lui Brâncuși” (“The Sons and Daughters of Brâncuși”) and we had a great conversation. She recently called my house, one early Sunday morning and told me that she had read the piece in Dilema or that she heard me on the radio. It brings me joy to see people who can understand these types of nuances. Also, I have to mention that there are very few women brâncușiologists. So, we need to work on fixing this. (She laughs again)

How does your generation relate to Brâncuși?

It is difficult to make a sweeping statement, because I believe that myself and a few others from my entourage are the exceptions to our generation. The people I come in contact with have a very distant and critical view towards the fetishization of Brâncuși. Many people have worked on this issue or have been inspired by certain events and wanted to comment on it, which is what started “Fiii și fiicele lui Brâncuși” (“The Sons and Daughters of Brâncuși”). To be honest, I just wanted to have a conversation with those whose art pieces focus on Brâncuși and an exhibition seemed like just the thing. We would have loved to also hold it at MNAR – an idea that was sparked by Dan Perjovschi and was taken over by Valentina Iancu. But, in the meanwhile, the museum got a new director and it just didn’t happen. The first two episodes of the exhibitions were simply imagined differently. The one in Timișoara, had activities, fun and more radical stuff, with a potential of upsetting conservatives. The one in Cluj had a more historical approach, based on research and documentation. I’m preparing a new episode at Magma, in Sfântu Gheorghe. We’ll be opening the exhibition in the middle of September and it will be a mix of the previous episodes, plus one new artist. Speaking of Magma, I thought it was so interesting to discuss Brâncuși from a Hungarian perspective. I am very curious as to how this project will be received there. I just think it’s a really nice experiment.

The exhibition „Fiii și fiicele lui Brâncuși. O intrigă de familie” (“The Sons and Daughters of Brâncuși. A Family Saga”) can be seen at the MAGMA Contemporary Art Space in Sfântu Gheorghe, between September 15 and October 9. A project by Alexandra Croitoru, in collaboration with Dan Acostioaei, Brynjar Bandlien & Manuel Pelmuș, Simion Cernica, Rafael Dubreu, Teodor Graur, Monotremu, Ciprian Mureșan, Vlad Nancă, Dan Perjovschi, Sergiu Sas, SUPER US, Napoleon & Ștefan Tiron.

Main photography: The Ministry of Culture’s Facebook page

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea.