Cugir, the smallest Romanian city to rise up in the Revolution, found itself without public institutions on the evening of December 21, 1989. A furious crowd took cover behind buildings from warning shots fired by the police then used Molotov cocktails to set fire to the town hall and the police station. Two police officers were burned to death that evening by the revolutionaries. The next day, the post-communist mayor took office in the football stadium, where, in the absence of ballot papers, the citizenry voted with a show of hands. Fearing reprisals by Ceaușescu-loyalists, the new mayor carried two automatic pistols and a semi-automatic. How did the smallest city to rise up manage to defeat a dictatorship in a single day? And what made the revolution in Cugir so violent?

Some 300 kilometres from Bucharest, not far from the centre of the country, Cugir is a scissors-shaped settlement at the foothills of the Șureanu Mountains, at the confluence of the Big River and the Small River.

The armaments factory is situated at this convergence. It has been in production for two centuries and has two wings. The lower factory manufactures arms and domestic appliances, while the upper factory is a munitions works. Before the Revolution, the factory had 21,000 employees, working in three shifts. Now, the armaments factory receives orders from NATO and only 900 workers remain.

In the communist period, Cugir was of great economic importance. In ‘89, living standards were relatively good there. The factories were busy and, people say, the wages at the arms factory in the communist period were very good.

Because of the weapons factories, the Cugir area was heavily militarized and hidden from prying eyes. The city was a ”Romanian mystery”, in the words of Ioan Cristea, the first post-communist mayor. It was carefully watched both by the Romanian secret services and the CIA. ”There was a desire to break free”, he says 30 years later. ”You felt that pressure; you never knew who was going to denounce you”. It is said in the town that one person in five was an informer.

I talked to nine of those who participated in the events of 21 December 1989 or whose lives were marked by their city’s day-long revolution. Thirty years later, many of them can recall how that fragment of history unfolded, moment by moment.

On Thursday, 21 December 1989, the Revolution had spread to a number of cities across the country. In Cugir, the revolt started with a moment of silence in the tool shop of the machine works, where items such as lathes and grinders were assembled and repaired, for later use in the assembly of automatic pistols, sewing machines and washing machines. Many of the factory workers there had heard from their children, students in Timisoara, that bloody protests were unfolding in that city. Răducu Crăciun, one of the first strikers, was 24 and had been working at the factory since 1984. At the outbreak of the revolt, Răducu found himself in a section of the workshop. He recalls how on that morning the workers gathered and discussed the news from Timișoara. ”People were saying there was a danger that that city could be wiped off the face of the earth. You can’t imagine how easy it is to make people disappear”.

”Have you heard what happened in Timișoara? Let’s show we’re on their side!” said Crăciun, to rally his co-workers during their lunch break. ”What kind of men are you? We have to do something if we want to get rid of Ceaușescu!” said another worker, Elena Motioc. Elena worked in the tool shop too, in the testing area. She was 34 at the time. ”I hated the old regime so much and really wanted to change things because I had my troubles. My husband didn’t get involved in anything, he was a sap. So I took my life in my hands and did it all, even when it came to the Revolution”, she explains to me, one afternoon in her home. When we meet, she is dressed as though for another Revolution, in a coat with epaulettes over black clothes and a military beret covering her blonde locks. Her yellowed palms attest to decades of work. She recalls how a handful of people went from section to section that morning, urging the others to hold a moment of silence.

One by one, the machines in the mechanical workshop shut down and silence fell over the entire section. The electrical generator was also shut down. A loud alarm broke the strange silence in the factory. Răducu Crăciun tells how someone jammed the bell of crane with a matchstick, turning it into a siren. Ion Mărginean, a 35 year old engineer, headed for the exit beneath the puzzled gaze of the tens of workers around him. ”Whoever wants to follow me, can”, he told them.

Some gathered in front of the building and began to sing the Romanian national anthem in a low voice. ”We only knew one verse, because during communism all we knew was Three Colours I Know in the World”, explained Elena, who marched out along with Crăciun, Mărginean and three or four other workmates. When they turned around, a gulf had opened up between them and the mass of workers who remained standing at the entrance to the section. They felt their legs unsteady with fear. ”It makes my hair stand on end even now. They were extraordinary times and memories”, recalls the engineer Ion Mărginean, showing me the bristling hairs on his arms. They then turned around and urged the others forward. They all began singing the soon-to-be national anthem. ”So much hatred and resentment had built up in them that when it was finally released it was like an explosion”, remembers his workmate, Crăciun.

On the way out of the factory yard, they were joined by dozens of people from the other sections, including the soon-to-be mayor Ioan Cristea and the president of Cugir’s 21 December 1989 Association, Liviu Bulzan, who had come out of the manufacturing section. Cristea recalls that at that point there were about a hundred people.

The director of the factory and other managers blocked their way and tried to convince them to return to work. Some remember even being threatened with losing their jobs. But the workers pelted them with dirt and continued their march towards the town hall. ”You should have seen them run like rats when they saw how determined we were!” says Elena.

From the town hall, they set off towards the upper factory. ”There were people from the town, and children, and everybody was walking along with their fists in the air towards the other factory, shouting Down with Ceaușescu! For Timișoara! We were euphoric, Romanian style”, recalls Bulzan. Then they went back to the town hall, and you couldn’t see the end of the line of people”. People danced in a circle, performing a traditional horă.

They became furious as the afternoon progressed. Like in a game of Chinese whispers, a rumour swept through the crowd that some of the protesters had been arrested and were being held by the police. One name that cropped up was that of Ion Mărginean, an engineer from the tool shop, who was considered an intellectual by the communists. ”We heard he’d been arrested. They [the leadership] said that Mărginean, being a university graduate, was an agitator and had mislead us. How else could workers get such ideas, for God’s sake, they had no education”, explains his workmate, Elena. Everybody was afraid that those arrested would be forced to denounce their workmates and friends whom they’d started the revolt with. Mărginean explains that he had headed home when he’d seen that some people had got drunk and were looting shops. His pregnant wife was waiting for him at home.

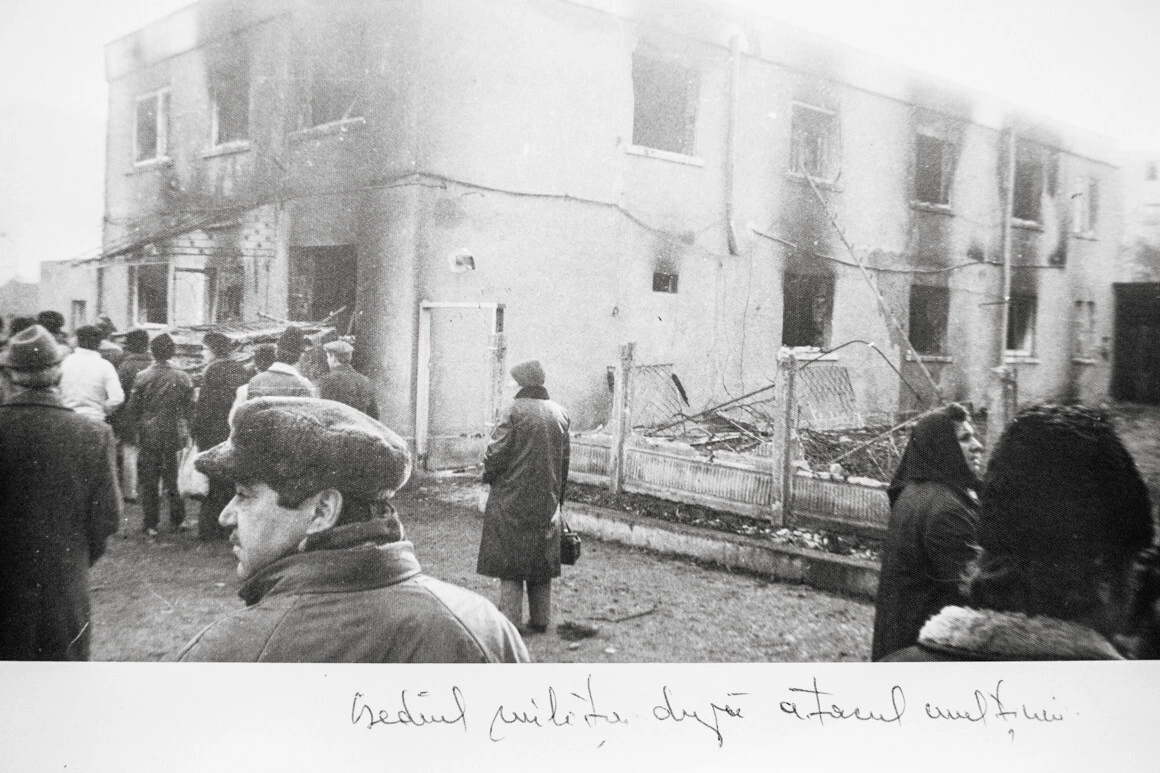

The crowd demanded that the police free those who had been arrested, but the commander on duty, Valentin Pop, denied that anybody was being held. Some claimed that members of the leadership and the Securitate were being sheltered in the building and that enraged people even further. An officer with the old Securitate from the city of Alba, lieutenant-colonel Ștefan Ceaușescu-Tătulescu, relates in the Romanian Intelligence Services magazine that he went to Cugir that morning and hid in the building that was later ”ravaged with flames” on the afternoon of 21 December.

The police opened fire at around 17:00. A rain of Molotov cocktails broke the building’s windows and the blaze spread from room to room. Some of the police fired in the air to frighten off the protesters. ”People took cover behind buildings and that’s when the real fighting began. They made petrol bombs from bottles and threw them at the police”, says Mărginean. ”You could draw petrol from the tanks of cars. You sucked it up through a tube”, explains Elena. The angriest of the protestors burned the cars belonging to the party secretary and the police.

Overcome with smoke, those in the police station flung the doors and windows open. Some fled through the woods dressed in civilian clothing, others went up to the first floor. When the flames took hold, they jumped down in front of the protesters. ”It was total chaos. Anybody with an enemy there looked for him in order to take revenge”, says Cristea. ”The police were beaten up, including those who didn’t deserve it. You couldn’t reason with anybody”.

In the end, only Commander Valentin Pop and Sergeant Ilie Staicu were left in the building. They jumped from a window and were killed by the protestors. Their burned corpses were then desecrated.

The violence of the police was common knowledge in the community. Some say the citizens took violent revenge against the authorities in retaliation for incidents in the past. Others believe people took out their rage against the regime on the last two of its representatives trapped in the police station. ”One day I went to the restaurant. They’d just beaten someone senseless and dumped him in a ditch. Some poor guy. I was so afraid”, recalls Florian Teodorescu. ”They abused their power, and mistreated people”, says Elena Motioc.

On the evening of 21 December 1989, the protesters set fire to the town hall, by then abandoned by the authorities. Nearly the entire city archive was incinerated.

”They cut off the penises (of the two policemen) and put them in their mouths”, says Valentina Nicula, the daughter of Valentin Pop, in her solicitor’s office in Alba Iulia. Above her desk is an icon and a drawing by her seven-year-old daughter. She speaks firmly about the past, as though it is a matter that is over and dealt with. ”People were furious. If there was a score to be settled, that was the moment to settle it”.

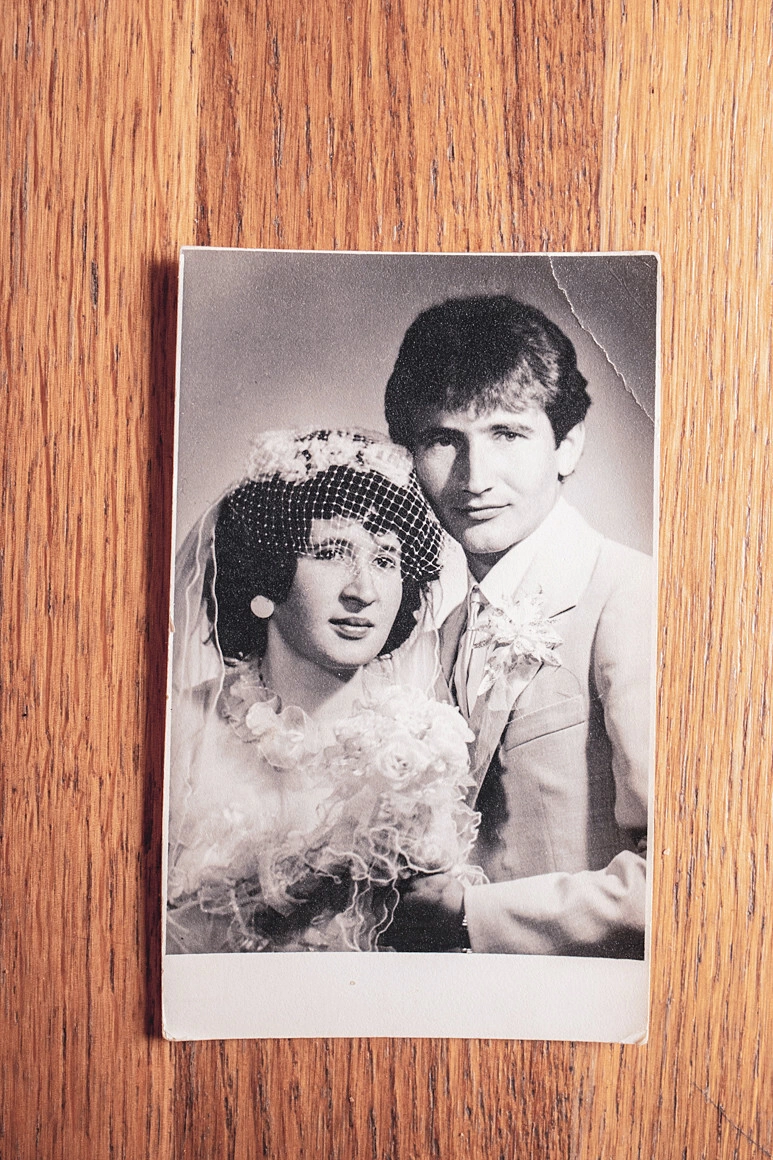

Valentina was seven when the Revolution occurred. She was in the kitchen, playing with her dolls when her father returned home for the last time, on the afternoon of 21 December 1989. He took a packet of pretzels his wife had made and said in a worried voice that he had to go back to the police station because there was unrest. Those were the final ten minutes the three of them spent together as a family.

That night, like many families of high-ranking functionaries, Valentina and her mother hid in a neighbour’s apartment. When the neighbours heard that public institutions had been burned down by angry protesters, they hid the list in the lobby that had the names of those living in the apartment block. Fearing the protesters, the families of commanders and police left their homes and brought their children to other addresses.

During the night, protesters could be heard in the stairwell as they went up to the apartments of known police officers. The neighbour sheltering Valentina and her mother guarded the door with an axe in her hand, while everybody listened to the sound of clothes and furniture being thrown into the street from the apartment above. ”The neighbours were frightened and told me not to sleep by the window. They were afraid the protesters might climb up to the first floor and smash the glass”, Valentina recalls. ”I got very upset and the neighbour’s children tried to calm me down by telling me my father was big and strong and could take on the lot of them!”

Those I spoke with gave varying accounts of how long the charred bodies lay beside the burned-out concrete shell of the police station. Some say they lay there for three days, as a symbol of revenge against an oppressive regime. Others recall them being removed the following day, on 22 December. Ioan Cristea says that as soon as he was elected mayor, he ordered the bodies removed to the hospital morgue. Pictures from the archive of the photographer Virgil Poenaru show a circle of adults and children staring at the uncovered bodies.

When their identities were established and the families notified, Valentina remembers asking her mother how they would now manage, with no-one to help them. ”Mama replied with perfect composure that everything was going to be fine. She gave me a sense of calm then that allowed me to carry on. If I’d seen her crying, I would certainly have panicked”.

Valentina’s mother wanted to know how her husband had died and made an official request for exhumation immediately after the Revolution. On 8 February 1990 she learned that Valentin Pop had died of his burns and not due to other violent causes. ”I would have understood had they attacked him with an axe. But in fact he was burned alive”, says Valentina, and for the first time in our three hour discussion she looks like she might cry. ”Losing a loved one hurts under any circumstances, but it hurts even more knowing how that man died”. She finds Christmas the hardest time; the holiday brings back memories and reopens the wounds she will always bear.

Eleven years after the Revolution, the Military Tribunal in Bucharest found four people guilty of killing the police in Cugir, sentencing them to terms of between 10 and 13 years in prison. In contrast, there were few convictions for the many killings of civilians throughout the country in December ‘89. An investigation was opened in the case of those responsible for law and order in Cugir, but no members of the old regime were convicted. Those convicted of killing the police have since served their sentences. Nothing more is known of them, except that only one may still be alive.

In Cugir, people immediately distanced themselves from those who killed the police. They say the killers were from Coșbuc, a neighbourhood “with problems”. A report by the Romanian Intelligence Services describes those convicted as ”unemployed Gypsies”.

”There were these Gypsies, ethnic Roma. I’ve no problem with … I’m just telling you who they were. The police know all about this community in Cugir. I see them now, when they have more rights: if there’s a robbery they tell me they look forward to being arrested. They have extraordinary conditions; there’s a room for conjugal visits at the weekend, if their girlfriend comes”, says Valentina.

When we met, Valentina recalls the reaction of one of the convicted men, who denied the charges and fell to the floor. ”It’s important that sentences to be imposed right after a crime is committed, so the person can understand why they’re being punished and for it to have a role in reforming the criminal. If you commit a murder in ‘89 and you’re not sentenced until 2000, you’ve had 11 years of freedom in which to formulate your own version of events in your head and you can’t comprehend the situation”, she says. When she grew up, Valentina wanted to be a police officer, like her father. But she wore glasses and the Police Academy did not accept those with poor eyesight, so she became a lawyer.

The following day, on 22 December, in the football stadium, Cugir held its first free elections. At nine in the morning the citizens raised their hands to vote. Ioan Cristea was elected. ”He was known as someone who could get things done”, says Radu Crăciun. As a dispatcher, he knew people in every section and dealt with every kind of problem which occurred at work. ”It was as though a new era was beginning. Everybody was happy, singing, dancing”, recalls Liviu Bulzan.

Cristea’s toughest decision as mayor was to arm the citizens to guard the city. In Cugir and throughout the country, rumours were circulating that bands of terrorists were on the way. “People were afraid that armed groups of Ceaușescu supporters would come and kill us for rebelling”, explains the ex-mayor. He supplied the bakery with flour and put the most troublesome of the townspeople to work to distract them from their anger. Then he sent people to reinforce security at another of the factory’s arms depots, in Vinerea, a nearby town. ”I didn’t sleep for three days and nights. I said to myself: if I let this crowd get out of control, the town is finished”, says Cristea. ”I had two automatic pistols, a semiautomatic and four full magazines on me. I was afraid. That was the situation; we were afraid and so were they. Nobody felt brave”.

The ex-mayor says he held the reigns in Cugir for three weeks, until the local branch of the National Salvation Front took control. ”They wanted to reinstall the old leadership. I didn’t agree so they got tough and said if I tried to stay on as mayor there’d be trouble with the old group”, he explains. Liviu Bulzan, the president of the December 21 Association, remembers the moment too. ”It was ephemeral, like a mimosa. I bloomed and then it withered”.

On 22 December 1989, on the road to Vinerea, a town seven kilometers from Cugir, a vehicle with citizens sent to defend the arms depot there skidded on ice and rolled over. Three passengers died. Among them was the 27-year old son of Florian Teodorescu, who worked in the testing station of the mechanical factory. Teodorescu tells how his son, Florin, when he saw him for the last time, asked for a bottle of wine from the cellar, to have something to drink with the lads at the depot. The next day, he was summoned to the hospital to provide information for the death certificate. ”I didn’t understand anything. I couldn’t function. I stood there for five minutes trying to remember”, the father tells me. He is a lean old man, with tears in his eyes. He doesn’t remember dates well, but the emotions associated with the event are fresh for him. That day he wanted to take his own life with a pocket-knife he carried as defence against terrorists. A nurse seized his hand in time. ”If my boy was dead, I felt it was all over for me. Maybe I wasn’t thinking straight, because I had another child”.

After the Revolution, the city of Cugir shrank steadily. In the first 12 years of democracy, its population fell by over nine thousand. Three of the nine people I spoke with have children who are working in other European countries, while the children of others are in bigger cities throughout the country. ”Romania could have been better in the last 30 years, if the young people hadn’t needed to seek better wages abroad. I feel let down”, says Elena Motioc, whose son now lives in Spain.

The factory suffered too, along with the people. The non-military manufacturing sections began to wind down in the ‘90s and much of the workforce sought employment abroad or retired. In 2008, fewer people were employed in the mechanical factory than had been a hundred years before, when there were a thousand workers. The remaining workers now meet orders from the private sector.

When the town hall’s archives and public records were destroyed by fire, a head mechanic who has served two terms as mayor, Aurel Voicu, created a place where local history could be preserved and protected. Since 2014, there has been a permanent exhibition in the old dormitories of the yard of the ”David Prodan” high school, where items of heritage value gathered from locals are displayed. ”If a great-grandchild has kept a photograph, we record the name on the display so visitors can see who has valued their ancestors and to encourage others to make an effort to find photographs of those who have gone before. There’s personal satisfaction in that”, says Aurel Voicu, as we walk through the 12 rooms with washing machines, looms and portraits of WWI heroes. ”It’s our duty not to just throw history on the rubbish-tip”. The only exhibit relating to the Revolution is two photographs of the town hall. One shows it before being burnt down, the other shows it after. ”This is the only city in Romania that burned its own archive”, says Aurel Voicu, disappointment in his voice.

Thirty years later, the Revolution has remained in the collective memory of the people of Cugir as a moment of youthful euphoria that promised more than it could deliver. Everybody wanted ”a better life”, but many of them now see their children seeking this life abroad. The revolutionaries still distance themselves from the killing of the police, and try to define what a revolution in fact is. ”If you grabbed a pistol and shot somebody, you were part of the revolution, that’s what happens in revolutions. But if you want to commit an outrage, that’s nothing to do with it”, believes Cugir’s first post-communist mayor, Cristea.

special thanks to Mihai Mateaș

translated by Philip O'Ceallaigh