People tired of the din of big city life, marked by personal crises or undertaking spiritual quests, go to live in an alternative community in Romania’s Apuseni Mountains. Alongside the quiet of meditation and a life close to nature, they are served a hefty dose of pseudoscience and conspiracy theories.

This report was initially published in the third print issue of Scena9 magazine, in which several dozen journalists, photographers, researchers, writers, artists, and philosophers discuss what our shared future might look like.

A metta morning

“May all the beings in the Universe, seen and unseen, be truly happy and released from their suffering,” all 70 of us in the meditation hall think to ourselves as one. We’re sitting on the floor, blankets wrapped around our waists, our eyes closed, trying to send compassion out into the world. “Let us expand the metta,” says the man guiding the meditation. Someone asks if they may send these thoughts to the homeless or to “puppies.” We can think of whatever we want, so long as we don’t recite the sentence as we would a poem. We then listen to a slow, otherworldly Indian song. Some of us burst into tears.

It’s almost 10 AM and the February sun, the chirping of birds, and the rustling of trees are coming in through the windows. A few burps, allowed in meditation, occasionally break the silence.

We’re at Children of the Sun, a community in the heart of the mountains, in Hunedoara County, where they teach Vipassana, one of the oldest meditation techniques in India. After centuries of having been forgotten, Vipassana was resurrected last century by S.N. Goenka, a former Burmese businessman who became a meditation teacher. The New York Times wrote that he brought mindfulness to the West. Among those who extoll the benefits of this technique, which has helped them focus better and influenced their work, there’s Israeli historian Yuval Harari, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, and artist Marina Abramović. “The entire exercise of Vipassana meditation is to learn the difference between fiction and reality, what is real and what is just stories that we invent and construct in our own minds,” explains Harari, the author of bestsellers Sapiens and Homo Deus.

Each year, roughly one thousand people from all over the world attend the yearly classes held in Dumbrava de Sus, where the Children of the Sun community has existed since 1997.

A class lasts for ten days and the rules are strict. You wake up at 4:30 AM, after the gong is sounded and the bells rings. You meditate for about ten hours per day, in one-hour long sessions; during that time, you sit still, your back straight. You can fold your legs under yourself, knees tucked in, knees to your chest or legs outstretched. During the ten-day class you are not to speak at all, except in the evenings, when you can ask your instructor questions about meditation. You have no access to phones, books, notebooks, radios, or TVs. Aside from these items, upon arrival, the organizers check that you haven’t brought along pens, hairdryers, sprays, perfumes, electric toothbrushes, heavily scented creams or oils, pills, food. You are only served vegetarian food and you sleep on a wooden cot, no mattress, in a room shared with several other people. The women in one house, the men in another. At 9:30 PM, it’s “lights out.” If you can’t take it, you’re free to leave. The classes are free of charge, but they recommend you make a donation at the end, if you’re happy with what you’ve learned, so that others can also receive what you have.

The purpose of Vipassana meditation is to help rid yourself of suffering, through eliminating mental impurities. You try to detach yourself by closely observing your breath and the feelings in your body, as you sit still. When thoughts flood your mind - past actions you regret, plans and memories, minor events, what you had for lunch, or some bill you forgot about -, you try to refocus your attention on your body and not react. If, for instance, you get a leg cramp or an itchy ear, you try not to move or scratch. This way, you learn that sensations are transient, that everything shall pass. At the end of the ten days of silence, you should leave there feeling calmer, with a balanced, compassion-filled mind.

The Dumbrava de Sus center is surrounded by mountains and valleys scattered with households. There’s a meditation hall here, houses for the attendees, and a few homes for the 70 community members. Close by, in the village of Țebea, there’s another core group, which largely works the land. The people living here grow most of their fresh food, in the field and in greenhouses. Children of the Sun is also on Workaway, an online platform which allows you to work in various countries. You work for a few hours a day and, in return, receive room and board. This is how an increasing number of foreigners from all four corners of the world has been coming to Dumbrava de Sus.

The entire community is organized on the philosophy of Ardelean Farcaș, the man who founded it in the ‘90s. Adi de la Brad, as he is known, is a burly 57-year-old blue-eyed man, whose gaze and smile suggest that he always knows something you don’t. He looks more like a shepherd than how you’d imagine a spiritual leader. He also leads the meditation session in which we “expand the metta,” so that our positive thoughts reverberate into the Universe.

After spending a few days disconnected from the world, Adi gives us a rundown of the news: there’s a disaster in Europe, the new Coronavirus has reached Italy from China, and Romania will also be affected as soon as possible. He tells us he was asked to help heal some people and has already sent to Italy a vial of black pebbles, which people are supposed to keep in their mouths for a while.

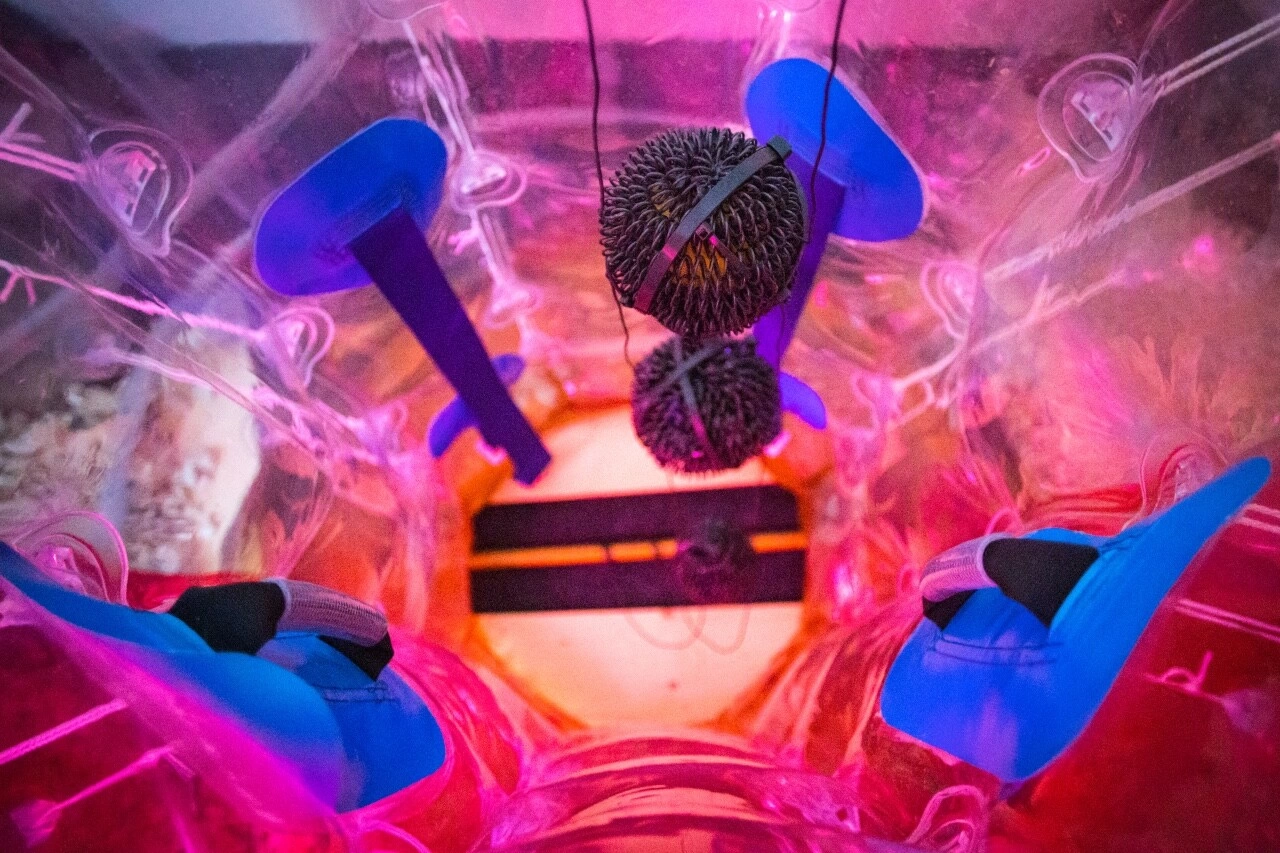

In the middle of the meditation hall, there’s a blue semitransparent plastic sphere, about 10 feet in diameter. It looks like a gigantic beach ball. Adi tells us that’s an Ark he built himself and that its powerful force balances people’s electromagnetic fields. He informs us it’s the first time he’s testing it out in class. “I’m glad no one died,” he adds jokingly. A few giggles in the room, a few puzzled looks around; I burst out laughing. But what if this Ark is dangerous?

The silence

I first arrived at Children of the Sun in the fall of 2019. I was a reporter for the country’s top daily, Libertatea - a coveted job for nearly any young journalist. Yet I was unhappy. I was always on the go, running around in all directions, constantly comparing myself to everybody else, and under the impression that everyone wrote more and better than me. I was feeling like I was going against my own rhythm. My personal life was also chaotic and I was trying to fix all this with psychotherapy and yoga.

I had found out about meditation classes in Romania and, since the Cluj-based center, part of the international Vipassana network, was sold out, I enrolled at Children of the Sun, which is not accredited. I had read a few comments online about the community leader, who allegedly “mentally manipulated” people and “stole women’s energy,” but three women who had already been there recommended that I go. It’s a wonderful experience, they assured me, even though the instructor sometimes says things “that might seem out of line, sci-fi, or taken out of a paranormal rag mag.”

I was happy to find out that Adi de la Brad was going to hold a lecture in Bucharest, a few days before the class I had signed up for. Warmly dressed, hat on his head, he sat in front of a room with an attendance of about a hundred people - the men to the left, the women to the right. Vipassana is not a meditation technique, he told us, but a way of life, to which he invited us to “give an honest chance.” It doesn’t require focus, he assured us, as focus boosts the ego; it only takes attention.

At the end of the lecture, he confessed that his body is host to a bacteria discovered by the Russians in the Siberian glaciers. “Translated into our language, it’s the bacteria of longevity or immortality. I am a meditator, so this bacteria developed. ‘Cause if I didn’t have this bacteria, where would I be now? I’ve been poisoned many times. By the communists, priests, wizards.”

A few days later, I was on a train to Deva. Even if Adi had said a lot of wacky things, he hadn’t left me with the impression that he was ill-meaning. My need to find peace was so strong that I ignored his deviations from the truth. On my way to Children of the Sun, I met Bogdan Dincă, this article’s photographer, with whom I was casually acquainted at the time. I felt a little bit safer. A car dropped us off at the foot of the mountain, where we started climbing through the forest, dozens of young people in colorful outfits.

Upon entering the center, the women were separated from the men, as the Vipassana tradition requires, we left our things there, and filled in forms with our identification data, professions, whether we practiced any other types of meditation, whether we had mental issues, or were on any sort of psychiatric treatment. As we had found out upon enrolling, people with mental or neurological issues were not allowed in the class.

At first, it wasn’t at all easy for me to stand still and perfectly silent for ten hours a day. All my problems and worries popped up into my mind and there was no way for me to shake them off with a Facebook session, a book, or a chat with a friend. All I could do was cry during meditation, on breaks, and before I fell asleep. Sometimes, when I felt like bawling, I’d clench my jaw, so as not to bother the others.

At the end of the ten-day meditation course, I felt free. I had made peace with a part of my past, fears, and pains. My mother’s voice had often emerged in my thoughts - when I was a child, she told me she had wanted to abort me and I realized I had spent all my life seeking to be wanted. I had talked to her about it and I knew she meant something else - I didn’t want you and look what a child I could’ve lost -, but her words had taken a larger toll on me than I thought. I forgave my parents and forgave myself for all the bad decisions I had taken. I learned to accept that nothing of what had happened could have happened any differently. Not the death of my father, when I was eleven, and whom I missed so much.

I returned to Bucharest feeling extremely grateful for this experience and found out that many city-dwellers who had gone there to meditate, people of all ages and social classes, artists, corporate employees or workers, left the place feeling the same. The reasons that had brought them to Dumbrava de Sus were different, but they often had to do with tough times in life. People undergoing personal crises, tired people, suffering from depression and other serious illnesses, or who wanted to free themselves of addiction; or spiritual seekers, fueled by pure curiosity.

Photographer Bogdan Dincă and I decided to report on Children of the Sun, to better understand what made some of the class attendees start their life over from scratch and move out there - as well as what comes after that. At first, the place had struck me as a sort of monastery for the young, where you withdrew when you no longer found your place in the known world, but where you didn’t have to say dozens of paternosters every day or bow to a sole god. Yet, gradually, I discovered new forms of obedience here.

In order for the people at Dumbrava de Sus to decide if they’d allow us to document their lives, we spent another week with them. We weeded carrot beds, picked roses for making jam, did dishes, picked out triticale - a staple grain in the cooking there -, and meditated by the Ark at least once a day.

Before we left, we paid Adi a visit in Țebea, where he confessed to us that, among other things, his goal is to have 500 heirs, so he could create a new human species. At the end, he looked at me and said, “You are so beautiful! If I make you a baby, what are you going to write?”

Although I’d kept my impression that the spiritual leader of the group meant no harm, I came back home with a new question: can you cause harm even if you mean well?

A short while later, I found out that Bogdan and I had passed the test and no member of the community had opposed us reporting.

“Do not exile yourself!”

The sky is orange at sunset and we’re heading toward the home of Damia, the newest Children of the Sun community member. She lives here with her partner, Marius Căpîlna (Sică), and Amza, their one-year-old son. We walk through a pine forest, where you can sometimes come across wild boars, and Damia touches a juniper, which she tells me is used for making gin. That’s one of the many things she’s learned out here, along with recipes for syrups, jams, plum brandy, floral water, or sundried tomatoes. Sică stops to saw off some hazelnut branches, which he uses as poles to prop up the tomato and bean vines. He enjoys digging, planting, building, “anything that helps other people come here and meditate,” says the 23-year-old with a boyish air, and a perpetual smile on his face. “Living out here is fulfilling, if you see these things as a step in your evolution, ‘cause it ain’t easy.” In the winter snow needs to be shovelled off the houses and greenhouses, the firewood needs chopping and the fire needs building. During the other seasons, there’s farmwork to be done, sometimes for as long as twelve hours a day.

Their place smells of freshly mowed grass. The old-style house windows are painted blue, there are baby clothes hung out to dry, and some water barrels for watering the garden are perched on tall beams. Amza is sitting buck naked on a wooden bench. The young couple want to get him used to going to the toilet in nature from a young age, the same as all the other children here.

Until recently, Damia’s life was nothing like this. In 2018, at the age of 28, this dark-skinned, green-eyed, beautiful young woman sang along to trap beats, with breakout sensation Șatra B.E.N.Z., one of the most popular new bands in Romania. “I feel great in my new sneakers!/ Nike, 23, or Adidas Yeezy,/ Or Off-White Vans, yeee-yaaaa,/ Step out in front with your sneakers, that’s the point,/ Step in front, step in front, show off your kicks,” she’d belt out, in the electric lights of the video for “Adidașii” (Romanian for “Sneakers”), which has amassed over 16.5 million views on YouTube to date. The day the song officially dropped and the comments, likes, and congratulations started pouring in, the young woman had already rented out her Bucharest apartment and moved a part of her belongings to Dumbrava de Sus. She knew she had ended a chapter.

Damia had heard of Children of the Sun the year before, from some colleagues in the musical world - hip-hopper Shift and the guys in Șatra B.E.N.Z. They’d just returned from there and struck her as totally changed - they were calmer, talked about spirituality, and had started penning lyrics inspired by the peace they had found through Vipassana.

At the time, her career was on a meteoric upwards path. She had just left the troupe of singer Alex Velea, along whom she had danced for some six years and with whom she had released her first song as a vocalist. “Beauty is a phase/ It lasts so little/ What matters is what’s inside your soul,” she sang on the chorus of “Ești atât de frumoasă” (Romanian for “You Are So Beautiful”).

Despite her fame, she was a mental wreck. She had amassed a lot of frustration in all those years she’d been waiting for her debut as a solo singer, she had just left a long-term relationship, and her parents had recently separated. “I was looking for something to bring me balance, calm me down, because I wasn’t OK at all,” she told me one day, under a pear tree in the garden of the meditation center. Over the past few years, she had become interested in spirituality, she’d started reading the Dalai Lama and asking herself about the existence of God. Her mother is an Orthodox Chtistian, and her Syrian-born father is a Druze - a religious spin-off of Shia Islam -, but she says she didn’t grow up in a religious envirnoment. Her questions about the meaning of life came after she realized her accomplishments weren’t bringing her happiness. “The first time I got my apartment, I said that wasn’t it. When I’d put out a song and get likes on Instagram and have I-don’t-know-how-many millions of views, that’s when I’d feel fulfilled. And then that didn’t happen.”

At her first Vipassana class, pain invaded her entire body and she felt constantly agitated. Sometimes, she’d open her eyes, look around, and think everyone else there knew how to meditate, except for her. She slowly unlearned being in a constant hurry and started paying attention to what her body was telling her. “The first class really tore into me,” the young woman recalls. “I couldn’t believe that we’re born with so many things, but we’re not advised to see them in ourselves.” It was the first time in many years that she experienced ten consecutive days “with no disordered eating and chaotic sleeping,” no talking, phone, or drugs. A blessing.

She remembers resonating with what Adi had said at the end of the ten days, “that we need to trust ourselves, that we’re a spirit in the Universe, torn off from a little star, that you need to live out your experience on Earth beautifully and not exile yourself, work your whole life for a wage or for fame.” But, at the time, she resolutely rejected his invitation - “‘Come live with us, we’ve got room, it’s good. You’re afraid of starving, why are you out there, living like they do in a jungle?’ I thought I wouldn’t move here even if threatened at gunpoint.”

Once she returned to Bucharest, she couldn’t really find her place any longer. “I couldn’t be a part of the industry, of this madness anymore. Man, do I really want this thing, or do I want to be at peace?” Life on stage meant many a sleepless night, frequent trips around the country and abroad, dancing and singing in the cold, in front of crowds that expect energy from you. When she went out with friends, she no longer smoked weed and felt it was becoming increasingly hard for her to have fun, even though she’d known them since childhood. “How long can you go on lying to yourself?”

More classes at Dumbrava de Sus followed, alternated with spans of work, for which she was feeling increasingly less motivated. Once, after coming down from the peace of the mountainside and entering Bucharest, through the Militari neighborhood with its cramped highrises, she got scared by the car honks and the congestion of stores, signs, and colors. “It was as if I was having an epileptic seizure. One of those things just hit me, and I said, God, I don’t think I want to live here anymore.”

She wanted to find out who she really was, take off her borrowed masks, gestures, and language. Up to that point, she feels like her life had been a series of choices dictated by others. She’d taken up volleyball because that’s what her schoolmates were doing, dancing because that’s what the girls in her class were doing, then singing and writing lyrics because she had been told she had a good voice and was creative. In the fall of 2018, after her hit song “Adidașii” was released, Damia says she did the first thing she had ever decided on for herself: she moved to the Children of the Sun community. She was going to wear her colorful clothes, with sequins and fur, her hand painted jackets and shiny leggings, in a village by the edge of the woods. “I wanted to be meditating Damia, I no longer wanted to be ‘Adidașii’ Damia.”

When she started her new life, Damia shaved her head, as she had seen many community members do, both men and women. Adi de la Brad had told them hair is an electrical conductor and keeps you from focusing on meditation. When she looked in the mirror, she felt like a little boy. “It really does kind of hit you right in the ego.”

The founding parents

One summer in the late ‘80s, Rodica, a blue-eyed 17-year-old girl, met a charismatic young man on a train. They’d both gotten on in Brad: she was accompanying her mother to a traditional dance in a nearby village, he was going home, to Țebea, alone. The man asked her to the dance in his village, but didn’t manage to convince her.

Thirty years later, Rodica, a soft-spoken woman, remembers that at the time she was a child “who hadn’t gone out into the world”, with simple, country-folk parents, and a violent father; she was instantly impressed by the man on the train. “There was something different, special, in his eyes and in the way he communicated, the way he knew how to envelop me with his, like, spontaneous knowledge.” A few weeks later, they met by chance at another village dance. When Ardelean Farcaș showed up “like Cinderella,” at midnight, the woman realized he had charmed everyone. “By the time he got to me, he’d danced with all the other girls in turn, but every time he’d look at me, to see how I reacted to the fact that he wouldn’t dance with me.” He eventually did ask Rodica to dance, too; in his arms, she felt something special, just like the time she had met him on the train.

As they were hopping around to traditional music, Ardelean, six years her senior, asked her to marry him. In return, Rodica asked for some time off to complete her studies; she was in the tenth grade and wanted to pursue her mechanical highschool studies, while also applying to a shoemakers’ school. They continued seeing each other and got married seven months later. She enjoyed his attention and the fact he respected her “simplicity” and those around him. But the spiritual bond she felt with him mattered the most. “[I wanted him to be] a fulfillment, a reconciliation for me, because my mother had suffered a lot with my father. There were many arguments, many scandals, and I decided that, at least for myself, I wanted something else.” Shortly afterwards, they had a daughter and a son, who are now also living in Dumbrava de Sus.

When she met Adi, Rodica was a religious woman, who prayed a lot. She was born into an Orthodox family, but attended Jehova’s Witnesses sermons for a while, too. She quickly gave up, because the leaders there struck her as “very possessive, dead set on indoctrinating you.” From a young age, she had realized earthly things don’t make man entirely happy, so she kept looking for answers. She wanted to understand why people “are so mean, why they argue, why they don’t see eye to eye, why they create so much suffering in each other.”

In the ‘90s, the two newlyweds would leave their children in their parents’ care and go off throughout the country selling medicinal plants, all-natural creams, and tinctures made by them. They sold best at yoga classes, which had flourished in post-revolutionary Romania.

*

In 1990, articles on Hindu spirituality printed by the freed press, the arrival of certain guru-teachers to Romania, and spiritual tourism to India were essential to the expansion of yoga groups and Indian-inspired religious movements, writes researcher Liviu Bordaș in the book Handbook of Hinduism in Europe published this summer by Dutch publisher Brill.

Under communism, yoga had been repressed for a long period of time. Condemned by the regime, it was practiced in secret at first. The only place where public hatha yoga demonstrations were allowed was the circus. From 1964 onward, owing to the USSR’s opening toward yoga, it started becoming accepted in Romania as well, especially as physical education and medical calisthenics. Articles on its benefits were published and it was included as a relaxation method in psychiatric research. In the early ‘70s, a yoga committee within the Health Ministry was founded. Yet publishing handbooks was under strict control: only nine such books were published in Romania by 1982, when yoga was once again prohibited and the groups that practiced it came under persecution.

After the Revolution, yoga was reborn. The Yoga Committee within the Health Ministry was reestablished, under the lead of a psychiatrist. It was very briefly operative, but it did manage to release a few permits for teaching yoga classes. Gregorian Bivolaru was the first to make his meditation school official after ‘89, writes Bordaș. In the first month of freedom, Bivolaru and 20 of his students registered the International Movement for Spiritual Integration into the Absolute (MISA), which had amassed 20,000 members by ‘97. The MISA leader was later charged with human trafficking and organized crime offenses, and, in 2013, sentenced to six years in prison for “continued sexual acts with a minor.” Gregorian Bivolaru was released on parole in 2017 and the organization he founded is active in 250 Romanian localities nowadays.

The Group for Transcendental Meditation, annihilated under communism, was also reborn after the revolution, in Bucharest and Cluj-Napoca, and, in 1993, Nicolae Iftene, a former painter who had fled the country during communism, would be the first to bring Vipassana to Romania, in Iași. He had learned this technique in Australia, in S.N. Goenka’s tradition.

Nicolae Iftene, who returned to Romania after 25 years of living in Australia, tells me over the phone that he taught Vipassana classes in the mid-90s, in highschools, student camps, and balneary resorts, where he’d rent out rooms. He says that in 1997 he collected donations from abroad for a meditation center in Romania and set out through the country to find the right place. That’s how he got to Brad, in Hunedoara County, where someone introduced him to Ardelean Farcaș, who knew the locally available plots of land. The latter then attended two classes taught by Iftene at the Strunga resort, close to Iași, and shortly thereafter laid the foundations of the Children of the Sun center, in which Iftene says he was not at all involved.

In 1997, says Rodica, Farcaș bought land and two houses in Dumbrava de Sus, with money from Fares, one of the best known Romanian plant-based product makers - to which he added their savings and other donations. He had chosen the spot, because, to him, it seemed “energetically charged.” Thirty-five youngsters moved there with him, enrolled by her husband from all over the country, but especially from Iași, while he was selling plants and tinctures.

Mihaela Ionașcu and Lușa, two of the first members of the Children of the Sun community who still live there today, were also a part of that group. When she met Adi, Lușa was a Psychology student in Iași. In the graduation paper she was working on, she had started from the premise that your pain threshold is higher when you’re relaxed, and someone recommended that she talk to Adi de la Brad. “When I saw the look in his eyes, I said, This is it. I knew this is a man who really knows what he’s talking about and he’s not talking out of books. I just felt it entirely: This is the man I have something to learn from,” says the 52-year-old woman in her yard in Țebea, as she pushes her four-year-old daughter in a swing. She named her older son Ardelică, as a sign of gratitude to Ardelean Fărcaș.

In ‘97, Mihaela Ionașcu had just graduated Philosophy and was a social worker when she met Adi in Iași, at a conference on alternative therapies. “My subtle sense told me that he was a special being, that he is something I’d never met before. He didn’t impress me intellectually, although I was into intellect, but I also had an underdeveloped spiritual side. When he said he wanted to found the association, I knew I had met the person with the necessary strength to help me fulfill my dream of helping people.”

Mihaela was working for Child Protection Services and says she’s seen all forms of suffering. She had dealt with abandoned, mistreated, HIV-infected, or cancer-suffering children. She had helped both them and their parents to the best of her abilities - with clothing, shoes, a kind word; but she felt it was all to no avail. “After eight years, my job had exhausted me both physically and mentally, and the people were still flooded with the same problems. After I meditated, I realized man needs to be taught to fish and find the cause of his suffering himself. Pity knocks you to the ground, but compassion builds you up into a beam to support the Other.”

Slowly, Children of the Sun expanded through sponsorships, donations from former students, and selling their own products: vegetables, “plasmatic products,” which they say are therapeutic, and, of late, crickets, which Adi believes are the food of the future. At first, the locals were suspicious of him and would put out rumors regarding organ and child trafficking. Gradually, however, the people overcame their fear and many think highly of the meditators. As for their spiritual leader - “good on him for having populated that land there. It would’ve been barren if it hadn’t been for them,” villager Elena Sauca told me.

Nowadays, 70 people are permanent Children of the Sun residents and Adi says his association owns hundreds of acres of land and several houses. In one live the men, in another the girls and single women, and in a third one the mothers with children. There are also a few camper vans, tents, and small, recently built homes, occupied by a single family each. Of the initial group of 35 founding members, Rodica says 15 of them are left.

Within the community, Adi now has four extraconjugal female lovers. He has four children with them. “It’s extraordinary,” his wife says, when I ask her how she feels about being in this position. “It’s an experience I’ve never even dreamed of. But I thank the Universe for gifting me with that peace and inner understanding, because everybody loves, everyone has the right to love. When you move past jealousy, everything is peace and quiet and fulfilment and love.” She then sighs: “It’s not easy.” She says she respects her husband and offers him her entire support, both on Earth, as well as “on other planes.” She has often wondered what her life would have been like without him and she believes it would have been “empty” on the spiritual plane.

A small scale society

The program according to which Children of the Sun functions and the philosophy it’s predicated upon have largely been set up by Adi de la Brad, starting from a few Vipassana principles he’s adapted.

Damia says she wouldn’t have stayed on if the rules had been as strict as the ones established by the man a few years back - waking up at 4:30 AM every day, meditation, then work - and if gender-based segregation had been mandatory in all cases. “It was an experiment, I think. At the end of the day, life on Earth is an experiment and no one’s forcing you to be a part of this place.”

The young woman thinks she’s lucky for being one of the few who are allowed to live in a small separate home, because she couldn’t picture herself alone with the baby in the mothers’ house. The couples who have no other choice adhere to this rule.

Damia and Sică plan on building their home with their own money, but at times they do wonder if they want to stay here forever with their child. “Amza is a great thing that happened to me, I don’t know if he’s the best one, but he’s a beautiful thing, and I think if I’d stayed behind in Bucharest, he wouldn’t have happened.” Damia says she and her partner strive to offer him everything they think is best and not deprive him of information. They have internet access and would like their son to learn English, Spanish, and whatever else he wants.

At present, the roughly 20 children in the community are being homeschooled - they’re being taught to read and write by their parents. In a few years’ time, Damia would like Amza and the other kids to be involved in group activities, as they once were. “It’s tough being both a teacher and his friend, teaching him both Geography and Romania.” Seven children were born at Dumbrava de Sus last year, so, in the future, Damia hopes that the parents will all come together to organize a shared schedule. She’d like to teach them dance classes.

She says the kids raised here speak English, know how to use the computer and the internet, watch movies, and have interests typical of any regular teenager. “I don’t think they’ve been deprived of stuff, and I think meditation gives them a lot of self-confidence.” Damia was the only parent who allowed us to photograph her son Amza from behind. Adi prohibited us from taking pictures of the other children, because he says people would transmit bad thoughts to them if they saw them.

The artist receives a child raising stipend, an allowance, and intellectual property royalties for the songs she was featured on, so she can afford to eat other stuff than what they receive from the center. “Generally, you lack nothing out here. But, well, when I was pregnant I did crave for an avocado, a mango. And I want the baby to have millet, amaranth, quinoa, some stuff you can’t buy out here.”

Since she’s moved to Children of the Sun, Damia has been weeding vegetable beds, has picked fruits and veggies, picked hay, milked goats and taken them out to graze. Aside from the daily chores, she also works as a translator for the meditation classes, but doesn’t get paid for it. Farmwork is also for free. Community members only receive room and board.

Aside from farmwork, the Children of the Sun share the tasks when classes are held for people outside the community: they clean, sound the wake-up bell in the morning, cook. Some of the people here, Damia says, “become immersed in work, just like they would in the city, others become immersed in their children. You find a refuge, read, hang out online, play a mobile game, there’s stuff like that here, too.”

In their spare time, the youngsters go swimming in a lake nearby, lounge in hammocks, and gather around a fire in the evenings. When she gets pangs of longing for all that she left behind, Damia picks up a small speaker, goes out into the fields, and dances.

When she and the others out here hit a rough patch, they meditate. The meditation hall is closed outside the hours scheduled by Adi, one in the morning and one in the evening. The work, however, can be done whenever. This summer, the Children of the Sun only meditated for a single hour per day, in the evenings. They couldn’t wake up early because of the accumulated exhaustion from working in the garden, in the fields, with the goats, or in the “plasmatic technology” lab.

Starting this year, thousands of crickets live at Țebea, in a room decorated with linoleum flooring and black plastic grates. Vlad Abrudanu, a 20-year-old Cluj-born man with a degree in Psychology, who moved there this year, is the one in charge of raising them. Adi says he’s brought the crickets in from Germany and Italy and that he wants to mate them with local crickets. He makes a “cricket protein” solution from them, which allegedly benefits the immune system. He claims he doesn’t kill the insects during the preparation process, but allows them to enter a hibernation state. Before becoming a human cure, the critters jump around in egg cartons filled with hominy, cucumbers, and vials of “electromagnetic grains.”

Adi de la Brad

It’s a fall evening, but the sun is still up, the clear sky traced with pink strips. Adi is sitting on a wooden chair by the pitch where several boys and girls are playing soccer. He’s holding a red cap, which he keeps putting on and taking off.

Next to him sit three of his four partners outside the marriage, with their sons. They bring them to Adi, in turn, to play with him. The youngest is around one-year-old, the oldest around three. The man affectionately calls all of them “daddy’s little mouth,” kisses their cheeks, and pinches their noses: “My God, children are so pure!” He calls one of the women to have her massage his back. She asks him if he’s had anything to eat. There’s a speaker in a tree, playing Transylvanian folk music. “From today until tomorrow/ My love keeps toying with me/ I’m not one to fool around/ And I want the best for you, my dear.”

The man closes his eyes, takes a few deep, heavy breaths, then presses his hand onto his temple. He’s feeling ill. Bogdan the photographer wants to take a picture of him. “Please, don’t, I’m wearing this protection and I don’t want this secret to transpire. I’ve been poisoned. They threw something in my face in a place near the river Prut and I had a quick commotion. I dropped to the floor last night, now I’m recovering,” he tells us. He then warns me not to write about these things, because I’d be taking on the responsibility for whatever might happen next. It’s at least the third time I hear Adi saying that someone tried to kill him. This time, he says it was some relatives from Israel who wish him ill and who threw a vial of poison through the car window. “These guys have a reward on my head, because I teach people to free themselves of tiredness and that’s the secret to immortality, to stop people from being tired.”

In about half an hour, the online meditation, broadcast live on Facebook, is set to begin, and Adi turns up the music. He recounts having been a folk musician who played the taragot, and that he used to make more money than he could fit in his pockets. Then, that he was a spy who made it to Captain rank within the Romanian Secret Services, but that the Securitate secret police kept apprehending him in the street in ‘84, when they wanted to execute him and other “paranormals.” “From that time, I’m left with some sores on my body, where they irradiated me.” Apparently, the only ones who escaped were him, father Iustin Pârvu, and quasi saint figure Arsenie Boca, about whom he says was his cousin.

It’s hard to separate fact from fiction in Adi’s life, as he tells it. He’s constantly adding more and more absurd details. In his version, he’s over 100 years old, has 80 children in various corners of the world, is descended from Slavic princes, and hails from a family of meditators. He learned meditation from a grandfather and his father, who is also in his 100s, lives at a temple in India. Aside from being a spy and a folk musician, he adds he was also a psychologist and trained secret agents, both in Romania, as well as in Dubai. “I now have a private pension of 17,000 Euro, I receive it in Switzerland. The bank teller goes all wide-eyed whenever I take it out from the bank. In 1990, I paid for a private pension amounting to 150 years of work.”

However, Simina Lazău, Adi’s sister, who lives in the village of Țebea, outside the Vipassana community, says their parents didn’t meditate. The mother was a housewife, and the father, who worked as a miner, died five years ago. She doesn’t know a thing about his career as a spy. The woman says her brother graduated thirteen years of school at the industrial high school in Gura Barza and worked at the Shoemaking Cooperative Moțul Brad, served in the army on a ship in Turnu Severin, and worked at the Țebea coal mine.

Vasile Popa, a former bookkeeper at the Țebea mine, confirms that Ardelean Farcaș actually did work there. “He supervised the workings of the ventilator. He’d introduce clean air in the mine. He had to be very careful there.” Mihaiu Gorcea, mayor of the Baia de Criș commune and a former engineer at the same mine, adds that Adi also worked as an underground locksmith. “There were transporters carrying the coal there. He’d fix the transporters if they broke down and supervised the production flow.” Gorcea also visited the Children of the Sun, to see for himself what’s out there and says he was impressed that Adi brought water pipes all the way up to the top of the hill. “He’s an OK guy, it’s just that it’s like an army barracks out there, and he’s the boss, ordering them to work: that guy does this, that guy does that.”

The Children of the Sun community founder claims he met professor S.N. Goenka in Dubai in ‘99 and, after a class that lasted for a few days, he received a certificate from the latter, attesting that the technique he teaches is Vipassana. However, he doesn’t want to show us this purported document.

“Mr. Farcaș was never named [a teacher] in our tradition,” states the teachers’ committee at the Vipassana Romania Foundation, part of the official international network of Vipassana centers. “The Dumbrava center is not affiliated to this tradition, they are in no way associated with Mr. Goenka. Of course, everyone is free to take part in any meditation class and we have no monopoly, but the students should know that this group [Children of the Sun] is in no way linked with S.N. Goenka,” the committee explained in an email to me.

In 1997, Ardelean Farcaș took two meditation classes with Nicolae Iftene - one as a meditator, the other as a servant - a volunteer who helps organize the classes. Iftene, who was named a teacher by Goenka himself in 1995, and who taught Vipassana in Germany and Australia, says that the process through which one becomes a teacher is lengthy and complicated. First, you need to take two classes a year and meditate for two hours each day, for ten years. Then, you need to take month-long classes and be a servant at least 30 times. Then, “you would be put under the observation of the senior teachers, that you do not kill, do not commit adultery, do not have children with all sorts of women,” Iftene explains, critical of Farcaș, who has children with “a whole bunch of students.” Only after Goenka’s personal assessment could you become a junior teacher, and receive the senior teacher status after some more classes. Adi de la Brad never went through this process, but “called himself a teacher.”

In a snappy tone, which I would have never associated with such an experienced Vipassana teacher, Iftene tells me Farcaș is a “pathological liar” and “a crook”, whom he accuses of exploiting the members of his community. What’s more, he claims Farcaș “threatened his female students they wouldn’t progress spiritually unless they had sexual contact with the teacher.” “First of all, they don’t do Vipassana there. They do Farcașana. It’s not different, it simply has nothing to do with Vipassana.”

“The Ark of peace and inner harmony”

At the end of the lecture Adi de la Brad held last year in Bucharest, a woman who had undergone cancer surgery asked for his advice. The man firmly told her she shouldn’t have “let them cut her up” and recommended a Vipassana class and some sessions with the “plasmatic module,” one of the many items he’s invented, sold by Children of the Sun on their website, energetik.ro.

Although in the Buddhist tradition Vipassana means seeing things for what they are, the spiritual leader’s perspective on reality is often distorted. Especially when it comes to health matters. Regardless of whether it’s cancer or COVID-19, all the “treatments” he recommends are made in the improvised community lab, by people with no scientific background: “mini Ark,” “plasmatic argyle,” “plasmatic bottle,” “plasmatic crown,” “plasmatic pulveriser,” “negatively ionized circles,” or “plasma vial for immunity.”

To get to the lab, you enter the bakery, pass the oven where bread is made, and reach a door with the yin-yang symbol on the outside and Mendeleev’s chart on the inside. The room is about the size of a typical living room, and on the shelves there are plastic boxes with various types of forming “plasma”, most of them in earthen tones. Above, silver and transparent hoses out of which the “plasmatic crowns” and “negatively ionized circles” are made. Jars filled with powders and liquids, multicolored vials and small bottles crowd the table. The air smells heavy, like at a balneary resort. We don’t have permission to take photos here, because, if they saw it, people might transmit negative thoughts to this place. And plenty of them already wish to do them harm, says Delia Burnham, a 40-year-old woman from the United Kingdom and one of the main people responsible for the products created via “plasmatic technology.” Delia moved to Dumbrava de Sus five years ago.

“The plasmatic crown,” a plastic circle filled with liquid, which all members of the community, including the children, wear on their head, promises to purify the mind and protect you “from social stress, the negative thoughts of those around you, and low frequency vibrations.” “Plasmatic argyle” is recommended for the widest range of afflictions, from stomach aches, anemia, or the common cold, to heart problems, varicose veins, vaginitis, muscle and joint pain, burns, and skin diseases.

Valentin Mortoiu, 38 year-old man who works in social security, has been a Children of the Sun student for a long time and sometimes stays behind after class for a few more days, to help out in the garden. Back home in Constanța, he wears the “plasmatic crown” and two “ionized circles,” one around his neck and the other around his waist. His understanding is that negative ions help him connect to the earth, which he misses, because he lives in a highrise building. He says he hasn’t felt any concrete effects, however; it’s just that the crown helps him be less scatterbrained as he meditates. Even though he doesn’t understand the technology behind the objects, he’s convinced that the community members “wouldn’t hurt people” or “scam them with anything.” Valentin met Adi de la Brad four years ago, at a detox camp. “He charmed me. He told us about some entities that live in our non-physical bodies and are parasites to it. And he somehow removed these things from the girls through a massage. He said he won’t touch the men,” says Valentin.

A year and a half ago, Ștefan Lipan gave up his postdoctoral studies in anthropology, which he was undertaking at a Belgian university, in order to look for his peace at Children of the Sun. He says that “plasmatic technology doesn’t go with the intellectual mind, ‘cause that one’s programmed, it’s doubtful. Here, things are intuitive. When I wear a crown in town, it’s easier for me. Without it, I come back exhausted after a day in the city, I come back listless, when all I did was to go shopping.”

Of all the objects invented here, the one credited with the most efficient “healing” properties is the Ark, whose name has been borrowed from the semantic field of religion. Christians keep the Eucharist inside the Ark, while the jews say Moses came down from the mountain with the Tablets of the Law inside such an Ark. According to Adi, the Ark charges people with energy, makes them wiser, and develops their attention and positive attitude. Besides, it also helps the animals, trees, plants, soil, and water, and protects them “against solar, nuclear, and 5G radiation.” Allegedly, it also saved Adi from being repeatedly poisoned.

Delia Burnham says that last Christmas Adi told her he wanted to create a new object. They both agreed it should be something round. “Since the Earth and the planets are spherical, he got this idea and I was always coming up with ideas that everything in nature is round, not straight.” The last large object invented had been the “plasmatic module,” a sort of cabin for “energetic re-balancing.” However, a single person could go inside the module at a time, so Adi decided to make an Ark, around which more people could gather.

Farcaș says he had the concept for the Ark since ‘97, but only last year managed to get all he needed in order to finalize it. “I couldn’t store telluric energy. I managed to do this through the electromagnetic grains designed by Davidoni,” he recounts. Ioan Davidoni, a self-proclaimed “eternal idealist,” worked for 30 years as a metrologist for a glass factory in Timiș County. Among his 900 inventions, we can find “the vibrating shoes,” “the magnetic bra,” “the anti stress magnetic shoes,” or “magnetic manure.” A “magnetic bra,” which consists of two hexagone-shaped shields made of “precious and semiprecious stones” and “noble” metals, worn under a regular bra, costs 188 lei. Davidoni promises it reduces the risk of contracting a breast disease by 90% and helps heal 60% of cases.

A major influence in designing the Ark and the other items sold by the Children of the Sun, as well as Adi de la Brad spiritual model is Iranian M.T. Keshe, the inventor of “plasmatic technology,” which he also discussed in Bucharest, three years ago, when the MISA School invited him to hold a lecture. Keshe, a controversial character, claims to have invented technologies for flying saucers, heal serious illnesses with his products, and, in brief, to be the Messiah. “I’m not ashamed or afraid of any leader or religious leader who tries to attack me. I created you and I can take your life at will. You’ve been waiting for the Messiah for a long time - here I am, in front of you,” the Iranian claimed at a 2014 workshop. In 2017, the Atomic Energy Committee of Ghana revoked the deal they had signed with the Keshe Foundation, citing a lack of scientific proof for building “the first space launch platform in Africa,” which Keshe had promised.

The main element in the Ark and the other allegedly healing products is the “plasma,” which the community members created in the lab inside the bakery at Dumbrava de Sus. Delia Burnham, who learned how to make “plasma” from Keshe’s online tutorials, explains the method. In one recipient, you put “two metal plates, tie them together with a copper wire, place them in salted water, leave them there for a while, and, if you also use heat, you’ve created an environment where plasma can become manifest. Illnesses are caused by an imbalance in your electromagnetic field.”

Physicist Octavian Micu, a scientific researcher with the Space Science Institute within the National Institute of Laser, Plasma, and Radiation Physics - Măgurele, says plasma is the fourth aggregation state of matter, alongside the solid, liquid, and gaseous ones. It is “ionized matter: a gas of ions and electrons.” Fire, lightning, the Earth’s ionosphere, and the inside of the Sun are examples of plasma, the researcher explains. This state can only be obtained in strictly controlled environments, such as nuclear fusion reactors. “The people at energetik are selling pseudoscience. To be clear: there is no type of plasma in those objects and there was nothing scientific behind making them.”

The Ark and all the other items are sold not only via the website, but also at the end of all the Vipassana classes held at Dumbrava de Sus. On the last night, you’re invited to a product presentation and, after having spent ten days in silence and you’re feeling that meditation helped, you can let yourself be convinced pretty easily that they will have an equally beneficial effect. The experience is so intense that reason sometimes only comes through once you’re back home. After my first class, I also bought a “bottle of plasmatic water” (125 lei) and half a kilo of “plasmatic argyle” (90 lei), in the hopes that they would rid me of my stomach pains. I spent half an hour in the “plasmatic module” for free. At home, after swallowing a teaspoon of argyle and nearly throwing up, I stopped the treatment and threw out the bottle at some point, while cleaning and realizing I no longer believed in its power.

In the beginning of my first class at the center, Adi told us to place one of these “plasmatic water bottles”, cap on, inside out water bottles, to help us meditate more easily. Although I didn't know what was inside and felt suspicious, so long as we didn’t have to drink its contents, I did it, too.

On their site, however, there’s also a “vial of plasma for immunity,” whose contents are poured into a larger quantity of water, and, once the sediments settle at the bottom of the recipient, you drink it in the morning and the evening, on an empty stomach. This allegedly protects the body against viruses and bacteria, improves “urinary functions and the emotional” system, and eliminates toxins from the body. It costs 70 lei.

We tested the content of this little bottle at the lab of the National Institute of Research and Development for Chemistry and Petrochemistry (ICECHIM). The results show that the “immunity vial” contains water, a fine powder, and grains that each contain various concentrations of copper, zinc, and iron.

Victor Ionescu, a resident epidemiologist and research assistant at the “Victor Babeș” National Institute in Bucharest says that, first of all, “metal oxide powders don’t mix with water. They remain in a solid state, decanted, no matter how many hours they’re left in there. Any amount that ends up inside the body is negligible.” The doctor’s conclusion is that this “immunity vial” cannot influence any bodily process, since its added elements “are not soluble in water solutions and cannot be absorbed along the digestive tract.”

*

Aside from “plasma,” the Ark also contains “little plasmatic brains,” some sort of metallic springs that supposedly transmit energy. Delia claims Keshe himself congratulated them for his invention, which could clean large bodies of water, from lakes to oceans. “The ideas and the form came through Adi and we helped him put it together,” the woman recalls. When the Ark prototype was finalized, “subtle changes started becoming apparent” in all the six people who meditated around it, she says.

They gradually started producing “mini Arks,” easier for people to bring back home. For meditators, a “mini small Ark” costs 2,000 lei and a “mini large Ark” 3,500, while for those who don’t meditate, they’re each 500 lei more expensive. They look like barrels of pickles with a few test tubes protruding from them. The prices aren’t listed on energetik.ro and those interested can only learn about them over the phone.

People in the community also place “mini Arks” in the greenhouses: they say they sense harmony and peace around them, while the vegetables develop more beautifully. The comments on the website from those who purchased them inform us that they helped some of them handle themselves better around people, cured them of depressive states or eye infections, while making pets more energetic.

“The Ark of Peace and Inner Harmony'' lacks solid scientific foundations to grant it any medical properties, but it does have “an extraordinarily important social function - to aggregate, define, and code the purpose of the spiritual community,” says anthropologist Cristine Palaga, university assistant at “Babeș-Bolyai” University in Cluj-Napoca. This ritualic object gains power so long as those who believe in its force gather around it. Its main function, Palaga explains, is to create “a sacred space, which allows breaking away from the mundane and mediating the relationship to the divine, understood as the pure form of a creative energy.” In a way, the Ark works in the logic of magic, the researcher adds, “through contagion”: once you come in contact with it, you automatically take on some of the promises of the supposedly magical object: “as direct a connection as possible to the immaterial/divine side of the self, protection, rejuvenation, healing, or the exorcism of those elements that pollute and block the being in permanent cycles of blame and suffering.”

“Usually, postmodern spiritual communities wish to re-enchant a world dominated by calculations, reason, and predictability,” says the anthropologist. And this re-enchantment is a first step in their breakaway from the society they criticize. “In these groups, it’s not just ritualistic objects that aggregate the community, but a so-called charismatic leader, a magnetic, fascinating figure, able to inspire devotion, and guide the community members towards a form of salvation, understood, in this case, as illumination and total liberation.”

“The entire vibration of meditation is found inside the Ark,” Adi told me the evening when he recounted the poisoning attempt by the Israeli relatives, to the tune of folk music. “Each man will be helped in accordance with how open he is. (...) I have become one with the Ark.”

*

Before coming to Dumbrava de Sus, Delia Burnham owned a recruiting company in Bucharest. “At a material level, it was all beautiful, but inside I was miserable. I was depressed, I was sad, I hated everything about my life, you know? I was trapped in a cage of my own design.” When she met Adi, she felt they had to work together right from the start.

One day, as we were picking beans off the vines in Țebea, Delia confessed that she’d found her peace in Dumbrava de Sus, but was pained by her inability to have children. Although she does have a partner in the community, Adi initially advised her not to be intimate with him, so they’d be purified. Four abstinent years later, he was also the one “pushing” them to have sex. One day, the three of them visited a farmer in the village and that’s where „[Adi] got us drunk. I had a feeling it would happen,” Delia recalls. She got pregnant, but miscarried shortly afterward. Several women then recommended that she see a doctor, but Adi was opposed. “He said, ‘You, Delia, a doctor? You need to trust nature that this is what was supposed to happen. Parents have a lot of sexual karma, shame, inhibitions, they’re not comfortable with their own bodies.’ Adi said it was as if my mother ate the baby, that I had unresolved karma with her.” He recommended two years of abstinence, to clean up her karma. The 40-year-old woman is worried she will wait all that time out and still won’t get pregnant.

Aside from getting involved in important decisions, Adi also controls seemingly insignificant moments in her life and the lives of other community members. He says this way he’s helping them evolve spiritually. Delia gave me an example from the previous day. She had slept in the afternoon, then swam in the lake, and wanted to eat before going back to work. “And then Adi looks at me and says, ‘You’ve eaten once today already, haven’t you? Please, go tend to the garlic, nothing’s going to happen to you.’ And I had such a strong inner reaction - not that I’d die without food, but I wanted to just sit and have a bite, ‘cause I was just feeling like it.” She didn’t eat and, half an hour later, she was no longer upset. She consoled herself with the thought that her work serves a higher purpose: “Your life is not your own. We really do live for everyone.”

Conspirituality

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Children of the Sun say they’ve sold a total of over 100 mini-Arks, big and small. The climax was during the months of lockdown. “Then, you could really feel people paying attention to themselves. Either they were panicking and needed protection, against radiation, for instance, or they wanted to meditate. The pandemic wasn’t about the virus, but about fear,” Delia believes. Adi de la Brad also thinks the virus is “a ruse.” Post-lockdown, when sales went down, the “bébé Ark” emerged, for only 700 lei.

Because he couldn’t hold classes during the state of emergency, Adi held weekly Vipassana classes broadcast live on the community’s Facebook account. Each session had about 80 participants, both from the country and abroad. Many expressed their gratitude to him and called him “teacher” or “maestro.” The classes were free and continued after lockdown was lifted. Some could also be attended by people who’d never been to a class before, if they were invited to the group by long-time students.

“Adi, what do you think about the whole pandemic situation?”, “Will there be a vaccine next year?”, “Will it get better when the vaccine appears?”, people would ask him on the chat. “We’d better not have a vaccine. Be very wise,” he answered to the camera. Instead of getting vaccinated, Adi recommends you buy “zeolite powder” from him, which you either put in the bath water in your tub or in your drinking water, in a large amount, together with a “cricket protein” solution, sold separately at their store. A liter of the substance goes for 300 lei. “Everything that is now manifested is just the beginning of a change of humankind. The animals will change, the politicians, everything. No one will be spared. (...) You need to understand very clearly that whoever has an Ark at home will be spared and get through anything.”

In a comment, a man told him he puts the Ark in his car and drives it around town, to help the others get through COVID-19 safely.

*

With the Coronavirus pandemic, which has gotten us used to living in fear and isolation, spirituality has become an increasingly trustworthy ally in all corners of the world. In the midst of chaos, people tried to reestablish a bit of order through any means, from yoga or mindfulness Zoom sessions, botanical therapies or astrology, to traditional prayer. At the same time, the pandemic has also bred fertile ground for conspiracy theories, which deepened the health crisis. Gradually, the two realms - spirituality and conspiracies - started to become enmeshed in certain respects.

Those who follow the phenomenon have revealed conspirituality, a concept coined in 2011 by researcher Charlotte Ward and David Voas, the head of the Social Sciences Department at University College London. The two show this phenomenon to be on the rise the world over; it stems from a total disenchantment with politics and the increasing popularity of alternative views of the world. At the same time, they point out, many New Age spiritual trends and conspiracy theories share a few core beliefs: the fact that everything in the world is interconnected, the fact that a secret group is controlling or attempting to control the social and political order, and that humanity is undergoing a “paradigm shift” of conscience. Conspirituality believers think the best strategy for coping with the threat of a “new world order” is “to wake up.”

In the Dumbrava de Sus micro-society I discovered such a universe of contradictions, in which meditation and a self-sustainable lifestyle close to nature is enmeshed with conspiracy theories and pseudoscience. Rodica Farcaș says all of her community leader husband’s exaggerations are meant “to provoke.” Other class attendants told me they could overlook the moments when Adi told them, for instance, that Obama had a house on the Moon, or when he prompted people to send compassion to 5G satellites, so that they’d send “positive waves” to the Earth. I, too, set aside a few of the absurd things I’d heard in the Bucharest lecture and came to the class to learn how to calm down.

But what happens to those who reach Dumbrava de Sus in the most vulnerable moments of their lives and start believing everything the spiritual leader tells them? To those suffering from grave illness and trust Adi de la Brad more than they do doctors? Who’s responsible for these people?

The history of alternative spiritual communities and utopian micro-society projects teaches us that when they’re centered on a charismatic leader, who cultivates his power, the road to various forms of abuse is almost inevitable and can sometimes creep up on you.

Those who leave

I met Irina* accidentally on a night out, when we started to chat and I noticed she was wearing a “plasmatic crown” on her head. She told me she’d lived at Dumbrava de Sus, which she’d left a while back. She doesn’t want to make her real name public, nor the time when she lived there and, although she was reluctant to share her experience at first, she eventually agreed. She decided perhaps it was time to end that chapter for good.

“I thought I’d found Mecca,” Irina recalls. When she took part in her first Vipassana class and heard Adi talking about life at Dumbrava de Sus, “I said I’d arrived where I was supposed to be and I blindly trusted that there are OK communities on this Earth, that people know what’s important.” She was captivated by what the people there had managed to build, she liked that they meditated and didn’t live with the stress of rent and bills, so she moved with them.

At first, she was told she could only take part in some of the chores and only if she wanted to, but shortly thereafter, she realized nothing was optional. If she worked less than others, she was excluded from the group. “People work until they become bitter,” the young woman recalls. “It’s like marketing: they push a certain image to the front - and I believed in that image. You have to spend a lot of time there to see some things and you have to want to and be brave enough to see them.”

What hurt her most was to discover that even the people there treated each other poorly at times. When they snapped at her, she recalled that, in the city, her employers talked to her nicely and even paid her. There, she worked for free and didn’t feel appreciated.

If she mentioned something they didn’t agree with, she got scolded. “It wasn’t OK to argue, it wasn’t OK to turn your back around and leave (…) I was bothered by the fanaticism. Only idolize Adi.” Only those who worked to the point of breaking their backs were allowed any kind of reaction. “If you work from morning to night, they don’t say anything. That’s how you earn your respect within the community.”

Although the others always told her they are one big family, she never felt integrated. During the time she spent there, she confesses she couldn’t be her true self - she didn’t feel sage. “I don’t want to say I was ideal, it’s just that they say one thing and do another. They say gossip is bad, but they encourage gossip there.”

Although the community claims to be vegetarian, Adi and other inhabitants eat meat, says Irina. The man explained his change in diet as a doctor’s recommendation. “All Adi does is that happens in society. People trust authority figures and hand over a part of their power to those figures. There, he decides what’s best for you, spiritually and mentally.”

Irina says the Dumbrava de Sus leader is “a sort of Alpha male,” with several partners, who “minimizes” the other men. “There are women who believe that if they spend time with Adi, he will help them on a subtle level to burn their karma, to evolve spiritually.”

During the time she spent with the Children of the Sun, Irina learned more practical things than she did during a lifetime spent in the city: to raise goats, farm, build, cook, chop wood. “These are priceless things,” she days. The most valuable one is meditation. “I think the greatest service you could give yourself is a Vipassana class.”

Both her and most of those I spoke to for this piece mentioned that, aside from the peace meditation brings, at Children of the Sun they feel useful and get the satisfaction that their work serves a greater purpose - creating a better world.

But when she drew the line, Irina realized she was paying too much for this. “I slowly started realizing I couldn’t take it. I saw that the world outside isn’t that bleak. It is bleak, but I got enough self-confidence to realize I had to leave there, because I wasn’t vibing. I left a part of my power there.” She tears up.

She’s grateful she was able to disconnect from the community, although it’s hard for her to live in the city. She’s now trying to find her place again, in a chaotic, polluted environment. “After living in nature for a few years, I don’t feel like working in an office anymore. It’s as if I’d be selling my soul, especially if you’re like me, and you haven’t found something you’re good at and enjoy doing.

Most of her current friends are also former Children of the Sun. It’s hard for her to reconnect with old acquaintances, because she thinks they no longer have much in common, but also because she doesn’t know what to tell them she did all these years. When she lived in Dumbrava de Sus, people would sneer. “You get judged a lot for having been there. People don’t have the capacity to understand communal living. I still believe communal living is the answer. But in another community, not this one.”

*

Epilogue

It wasn’t easy for me to navigate the nuanced universe at Dumbrava de Sus. Nor to separate the beneficial effect that meditation had on me from my work as a journalist, which was met with many moral conundrums.

Early on in the documentation process, I was afraid that this place would attract me so much that I would want to become a Child of the Sun myself. At a certain point, I even told my colleague Bogdan Dincă to take me out of there by force, should I, by any chance, decide to stay. In total, I spent 15 days as a simple meditator in the community, then a test week and another week of fieldwork. At the end of the first day of documentation, Bogdan took a picture in which I was beaming with joy, I don’t recall ever having smiled with as much as my being as I did then. Gradually, however, I began to understand how hierarchies work in this place, which promises peace and truth, and the fascination waned.

At times, I felt I was betraying a few people’s trust, by writing some information, which they later suggested I don’t include in the report. I decided to publish them anyway, because I feel like anyone who gets to Dumbrava de Sus, especially at a vulnerable point in their lives, has the right to know what they will find there, aside from meditation and quiet.

Irina* is a pseudonym.

Translated from the Romanian by Ioana Pelehatăi