A cloud of laughter rises up above the classroom. The Math teacher stops writing and turns around, angry. “Quiet!”, she yells. “Dana, please behave!”, she tells a 13-year-old student, hidden in the back of the classroom.

Dana has her head down. She buries herself in her sweater and tries hard to avoid the insults. “Peasant!”, “crow”, “gypsy!”. “Wash!”, “take a shower!”

She’s a nervous wreck. These words have been floating around her for about a year. Each time, they hit her with the same intensity.

“Dana, why do you provoke all this noise?”, her teacher asks her. She’s got short, brown hair, and wears glasses. “Leave the class for a while, give the children some time to quiet down.”

She gets up, hurries to the door, leaves the classroom, and then runs to the girls’ bathroom and locks herself in a stall. She starts crying, and puts her hand in the pocket of her jeans to find a metal pencil sharpener.

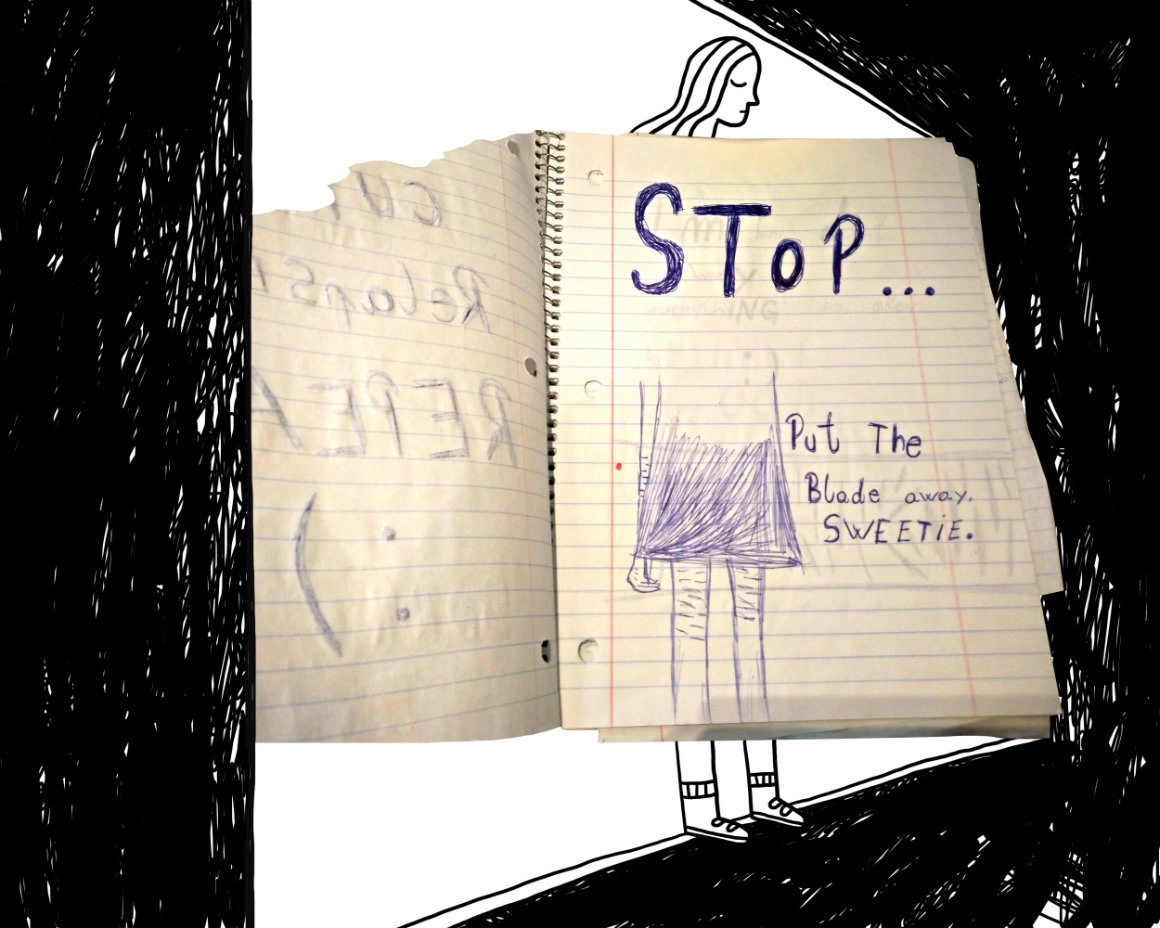

While crying, she manages to remove the screw, and take out the blade. She rolls up her sleeve and plunges the blade into the smooth skin of her left arm, close to the wrist. She closes her eyes and lets out a brief yelp, then repeats the action. She thinks about her 12-year-old friend, whose arms are filled with cuts. “When you start cutting yourself, the pain you feel in your arm dulls the pain that makes you cry”, the little girl explained to her in the schoolyard. But Dana now feels pain in both her arm and her chest.

After four cuts, she stops. She stays hidden in the bathroom stall for the rest of the class. Before the bell rings, a few girls open the bathroom door and see blood dripping in the sink. They get scared and run away. They talk to some of Dana’s classmates and her class teacher finally finds out.

“Do you think what you’ve done is alright?”, she yells at her. Dana stares at the floor. She’s got long hair, like a fairy, put up in a pony tail. Her hands hang limp.

“Now you’ve given them a reason to mock you!”

Close your eyes. Breathe, little girl. This will all end, everything will come to an end.

“It’s only your fault that kids laugh at you!”

“See, Miss, we told you so!”, Dana hears in her head the voices of the boys who have been mocking her for the past year.

After the talk, she rushes out the school gate and goes home alone.

This took place in March 2014, at the end of a school year that saw the student from the “Eugen Lovinescu” Bucharest high school repeatedly harassed by her classmates, under the lenient watch of her teachers. They laughed at her, called her names, isolated her, and ostracized her.

Dana didn’t know that she was a victim of bullying. In their school, nobody talked about it.

According to a study by Save the Children (Salvați Copiii), in Romania, 1 in 4 children is being humiliated in school, 3 in 10 are excluded from their circle of friends, and 4 in 10 have been injured as a result of a recurrent violent behavior exerted by their colleagues.

“Bullying is a continuous action, performed with the intent to harm and humiliate”, says Ciprian Grădinariu, one of the research authors.

The adults – generally, parents and teachers– perceive it as a natural strategy of the child’s social adaptation. “The teachers don’t see a problem with the constant harassment”, states Grădinariu. “And the parents’ reaction is along the lines of: «oh, come on, they laughed at you, you laugh at them».”

But bullying is not a random fight, or a kick in the butt, you forget about the next day when you’re out at McDonald’s with your aggressor. It’s the repeated actions – verbal, physical, or social (marginalization, public humiliation, and others) – that have a strong impact on the victim. “We’ve had children say during focus groups that they would have rather been beaten, than humiliated, because physical wounds heal faster”, says Grădinariu.

The results of a 14-year study on children from the UK and the US, show that the persons who had been harassed in school are inclined to experience mental health issues, anxiety, depression, and a lifelong of self-harm. The impact of emotional abuse from colleagues is comparable to that of sexual and physical abuse.

I met with Dana a few times. She’s a wary teen, who loves chocolate cookies and animals. She has a shy smile, doesn’t trust strangers, and reads anything and everything that she can get her hands on.

“Too Much Happiness”, by Alice Munro and “How I Became Stupid”, by Martin Page can be found on her nightstand.

“This book is about a guy who would like to, at least for a few moments, become stupid, because stupid people are happier”, she tells me. I open it and find a highlighted phrase. “A fish never knows when it’s pissing. The same applies perfectly well to intellectuals.” I ask her why she chose it. “Oh, yes! The stupid are happier, because they don’t know what they are doing. A smart person knows when they’re doing something, and that’s why they’re not happy.”

Dana’s problems started in the 6th grade, when she was 12. She was walking in the park with a few kids from her class. They were all mates. It was business as usual to mess with each other, climb trees, and paly ball during recess.

A blond girl, a classmate of theirs, came to ask her for a notebook for school and the boys began laughing at her and throwing rocks. The rocks were small, but many and were coming in waves. Dana stood up and asked them to stop throwing rocks at the girl. She thought they were exaggerating, that they were being way too mean. But the boys went on to throw rocks at both girls, so they ran away.

The next day, none of the boys were talking to her. For a while, they completely ignored her, but then they started calling her names. Shortly, all the kids in her class took their cue from them, and Dana was left with very few friends.

The adults in the school noticed that Dana was being isolated from her classmates and, as the girl recalls, they had even heard some of the insults directed at her, but they didn’t think it was anything serious. During Math, when she was asked to leave the classroom, the teacher thought it was too complicated to solve an equation with that many aggressors, so she removed the variable.

Mihaela, Dana’s mother, is a vendor at a small shop in Drumul Taberei, a few blocks away from the high school. She’s got a furrowed forehead and a soft voice. She found out about the blade incident, three days after it happened.

Dana remembers that the class teacher asked her to let her mother know about the incident from the first day that it happened, but she couldn’t do it. “I couldn’t just go to her and tell her I cut myself. I didn’t want her to find out, I was so scared and embarrassed!”

Three days later, the class teacher got a hold of the woman’s phone number and gave her a call.

“They should have called me on the first day”, the woman says bitterly. “My child could have died!”

In an official answer, the Sector 6 School Inspectorate of Bucharest claims that Dana’s mother had been informed “as soon as the class teacher found out the child was being harassed”, and that a police officer came and did a “classroom activity on the subject of harassment.”

When she saw her mother at school, Dana started shaking like a leaf. At home, the woman asked her to take all her clothes off so she could examine her entire body. She had cuts on both her arms.

“In Romania, teachers take action against the bullying phenomenon only when it escalates to physical violence”, states sociologist Ciprian Grădinariu, from Save the Children. “Until then, they either don’t see it, or they don’t consider it important. Sometimes, they themselves are the aggressors.”

Rosie Dutton, a teacher from Birmingham, did an experiment with her class. She brought two apples to school, and before the class started, she hit one of the apples against the table. The blows were gentle, and at the surface, the apple seemed intact, but on the inside, it was soft and brown.

She gave the two pieces of fruit to the children and asked them to say a few things to them. The abused apple received only insults – “apple, you stink”, or “you’re probably full of worms” – and the other apple only got nice words: “you’re adorable!”, “your peel is so beautiful!”.

At the end, the teacher cut up the two apples and the children were stunned. “They immediately understood the exercise”, says Dutton. “They saw what the inside of the apple looked like. The wounds, the bruises, the bits that fall apart are found inside every person who is verbally or physically harassed.”

Dutton wrote about her experiment on Facebook, and the comment section to the post was filled with thousands of confessions from victims, aggressors, or witnesses of bullying. “When people, especially children, are harassed, they feel horrible, but most of the times, they don’t show it, or talk about it”, says Dutton.

In some countries, bullying is considered a serious form of trauma and a public health issue. The schools and ministries are actively involved in reducing the phenomenon. For example, in the UK, where 46% of the children and young adults claim they’ve been harassed by their colleagues, the schools have dedicated anti-bullying strategies, and their implementation is periodically verified by school inspectors.

In Finland, the KIVA national program, managed to significantly reduce the number of bullying victims in schools. Aside from various instruments meant for parents and teachers, an important component of the program deals with working with the witnesses – children who witness the scenes of violence. The teachers realized that the witnesses are key, and if they choose to intervene, the aggressor stops. The students are taught, through simulations and computer games, to become empathic and to tell nice things to their classmates. The program is being tested in more European countries.

In Romania, the Education Ministry claims that it deals with the phenomenon in the context of the student’s safety in the school environment. As a response to our request, the Ministry mentions some ONG partnerships and campaigns meant to prevent juvenile delinquency and school violence. The prevention and involvement in cases of bullying don’t show up in any of the ministry’s action plans.

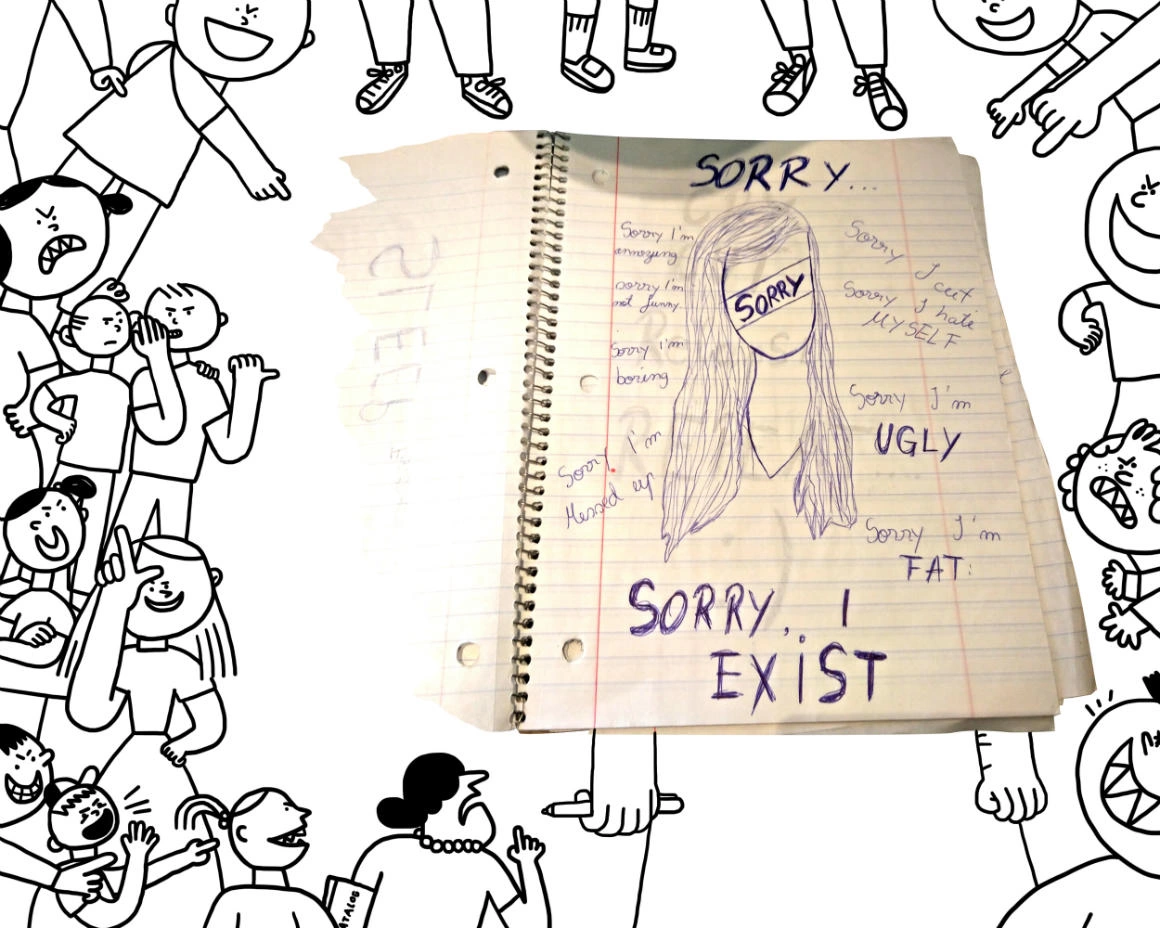

“They used to call me a «gypsy» and a «stupid nigger»”, Dana confessed about her classmates. “Usually, I didn’t say anything and I would just cry, but then when the teachers saw me, they would yell at me.”

At the beginning, it was only her class mates that would laugh at her, but soon the harassment spread to the whole school, with the same speed candy is handed out to children. During recess, Dana would sit alone at her desk. “I no longer belonged there.” She stopped focusing in school and her grades started falling.

“What got to me the most was when my classmates told me I should die. «Why are you even alive? What’s your purpose on this Earth? » ”

She was always crying. In class, during recess, on her way home, at home. Sometimes, she would cry so much that she thought her tears could create a river, long and deep. A river that would flow between the school and home and she could drown in it to avoid hearing all those people around her.

“At one point, I would start crying even if nothing was happening to me”, she tells me.

During educational class, the children would listen to music or do their homework. “I was always telling my class teacher that I was having issues. She would promise to talk to the boys, but she never did.”

A few of her former classmates with whom I managed to speak contradict her story. “When she wasn’t in the classroom, the class teacher would always tell the boys to stop being mean to her”, Ana remembers. Maria, another classmate, says that the “class teacher would talk to them, tell them to calm down”, and Iulia, who was closer to Dana, claims that “until her mother called the television, nobody cared about what was going on. From the teacher’s side, there was never anything more than «leave her alone», «keep it down» and «I’ll give you a bad grade!».

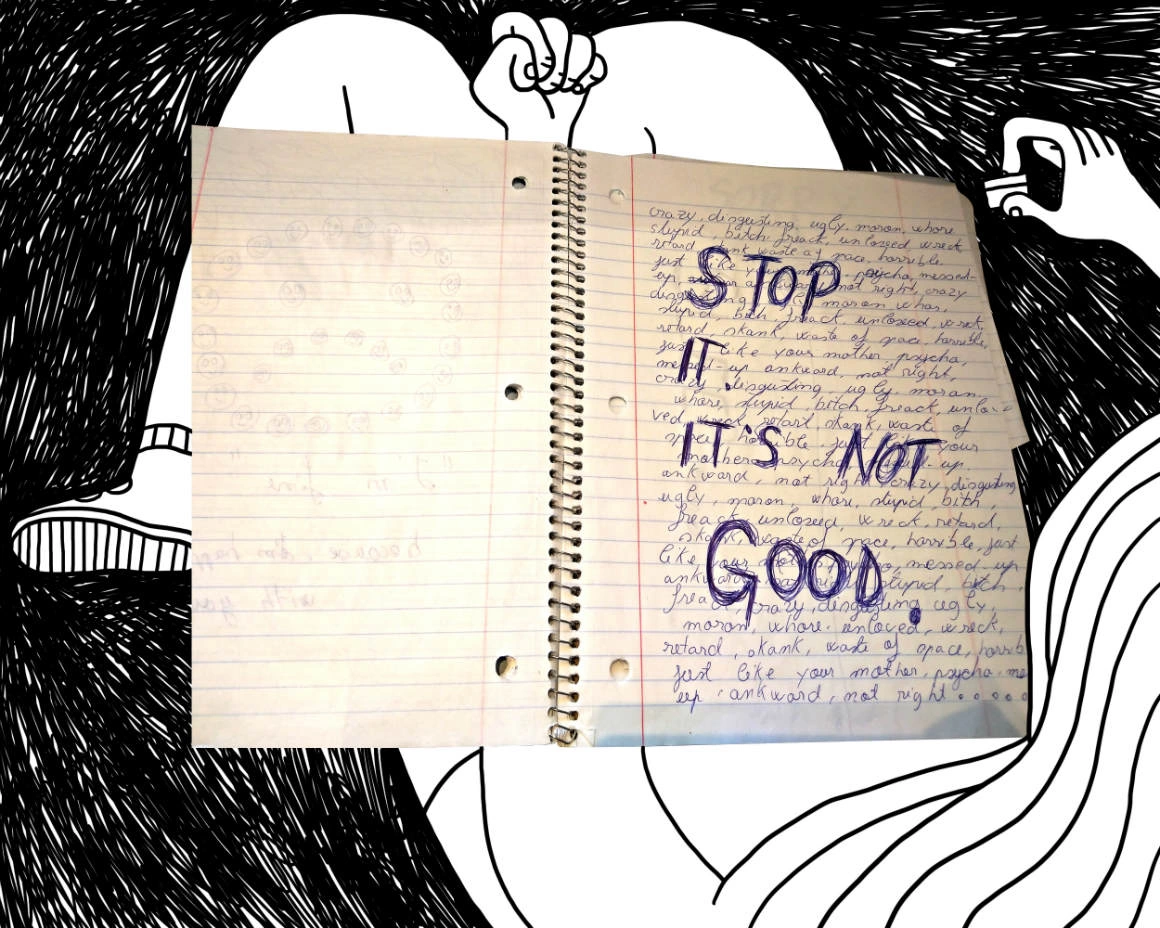

The children say that they laughed at her because she was a sloppy dresser and that she didn’t pay too much attention to her hygiene. The girls insist that they didn’t isolate her. That she started cutting her arms before the pencil sharpener incident and that she did it because of a former boyfriend. They had told her to stop, to no avail.

Before she left “Lovinescu”, the class teacher took Dana and a few of the boys who started the whole thing to go see the school phycologist. She remembers that the expert sat everyone down in a circle, and asked for details about the problem, and then told the girl that maybe the children had a reason to laugh at her.

“Why don’t you try wearing more skirts”, he allegedly told her. “Why don’t you style your hair with a curler?”, “Why don’t you put more effort into pleasing people? Maybe that way you would have less problems.” The boys triumphantly approved, like the good little boys they were.

One of the former aggressors regrets his behavior. “I wasn’t mature enough and I didn’t know how you really feel when something like this happens to you; even something as little as someone making a face at you”, says the boy. “One of my priorities at the moment is respect for people, I can’t even imagine laughing at someone right now. It’s very annoying when you get to experience this yourself, which is why I don’t want to cause this feeling to others.”

He remembers that some of the conflicts started because “there was an unpleasant smell in the classroom and our classmates would tell her “Dana, you stink!”. All types of things that are age-related, that lack maturity and discernment. She didn’t tie her hair up and had dirty nails, and that’s why miss counselor reprimanded her in our presence.”

A few days following the school bathroom incident, Dana went for a walk in the park with her neighborhood friends. In the evening, when she got to her room with orange walls, she discovered that someone had hacked her Facebook account and posted various messed up things on her wall: a picture of her on a railroad with the message: “not even the train wants me”, a photograph of a dirty bathroom as her cover photo and a series of swear words that suggest the 12-year-old girl was offering sexual services in exchange for money.

Dana’s mother got angry, and printed all the posts that showed up on Dana’s Facebook. She brought took them to the school, and she asked for a meeting with all the parents of the children who started the whole thing. But, when the time of the meeting came, all the parents of the children in Dana’s class showed up, and things got out of control fast. “They accused my little girl of being demented, and they called me an unfit mother who lives in cardboard boxes”, the woman confessed.

A police officer from the 25th precinct attended the meeting. Dana’s mother had filed a complaint, so they sent someone to investigate. The man jotted down some notes, and then he made himself scarce. The case was taken over by the Directorate for Investigating Organized Crime and Terrorism (Direcția de Investigare a Infracțiunilor de Criminalitate și Terorism, or DIICOT), but only a year later, it stopped prosecuting the case. “There was not enough evidence that someone committed this crime with an unknown author”, says Mihaela Porime, chief-prosecutor of the Department of Information and Public Relations DIICOT. In fact, the authorities claim that they couldn’t prove that someone had hacked Dana’s account.

“At school, there are sometimes teachers who act out the role of the aggressor”, claims Ciprian Grădinariu, a sociologist with Save the Children. “They don’t know that that repeated harassment is not alright, and that the victim will never get stronger, because they’re always the butt of the joke.”

From the outside, “Lovinescu” high school looks just like any other Romanian school. It’s got large, square windows, and a concrete yard. Here and there, weeds grow through the cracks.

Inside, the walls are filled with the students’ poetry and drawings. Noisy students roam inside its hallways.

The school’s principal, Daniela Beuran, is annoyed by my questions about Dana. “Why are you interested in a case that happened over three years ago?” She won’t let me talk to the math teacher, nor with Dana’s former class teacher, Liliana Voicu. She tells me that I should email the school. She’s also the one who replies to my mail.

“From our point of view, the case was closed three years ago. You seem to know a lot of erroneous details about it. According to the School Inspectorate of Bucharest’s image department, this case was very much embellished. (…) According to the rule of law, you are not to use the name of our high school or any of its teachers, in your article, in any shape or form.”

In spite of my persistence, she refuses to share the “erroneous details” with me.

Liliana Voicu, the former class teacher was just as eager to get over things. “I don’t want to dwell on the past”, she tells me over the phone. “She stopped being my student a long time ago. I believe that I’ve done my job. I’ve followed all the legal steps; I’ve done just about everything that was necessary.”

The math teacher doesn’t seem to remember anything. “I don’t think this happened during my class, because I would have known if it had.”

“Lovinescu” high school isn’t a first offender when it comes to bullying. Three years before Dana, Matei, a frail, little 11-year-old boy, was harassed for a year by his classmates and teachers. He was ultimately diagnosed by the therapists form the Save the Children organization with an emotional disorder.

When she saw that her little boy would start crying every morning, Matei’s mother began hiding recording devices on him, without his knowledge. “He was very calm at home, but when we would make our way to school, he would cry, shake, and became very agitated”, she admitted.

In the classroom, the children were laughing at him, they were teasing him, filming his reactions, and sometimes, they would even beat him.

Matei’s former class teacher called him “stupid” and “a moron” in front of other students.

„Go ahead and start writing, can’t you hear me? Are you stupid or what? You’re being an idiot again. You’re an idiot every single day!, „ Matei, the moron, closed the door again. Stop making that stupid face?”, „You’re a pain, you’re impossible, you’re laughing like an idiot again?”

After she publicized those recordings, Matei’s mother sued the teacher and moved her son to a private school, where he did therapy for years.

“I’ve fought battles on many levels”, she says. “I had to put Matei back on his feet, then to go through the trial. I wanted to prove that he was a victim of bullying, but our judges have no concept of that.”

She read Wikipedia pages, national and international studies on bullying, she sent letters to the Ministry of Education, and educated her lawyers. “The judges understood that this was a sensitive case, but that they didn’t have the required knowledge needed. They are used to looking at the direct consequences. What did the teacher do? Did they cause so much harm that hospitalization was needed? Does the child have a medical report to attest the injuries? This is what the police and the court are looking for. I had to talk to them about my child’s trauma.”

While this was happening, there was a petition floating around in favor of the teacher, which got over 200 signatures. Former students of his believed that Matei was subjected to a “so-called verbal abuse”, and that the whole thing was just a difference of opinion, and that this “doesn’t mean that we’re going to bring to justice anyone who works or thinks differently than us.”

On June 18, 2017, six years after the trial started, teacher Bogdan Sevastru, Matei’s former class teacher, was given a one year suspended sentence by the Bucharest Court of Appeal for “constant abusive behavior”. It was a first for Romania’s justice system.

In the weeks that followed the incident, Dana didn’t leave the house. Then, her parents moved her to another school. They barely managed to find an institution that accepted her. The girl’s case had appeared all over the media. The school principals all knew her and didn’t want her in their schools, for fear that trouble would find her there, too. After her parents tried their luck with six institutions, they managed to find a neighborhood school to have her.

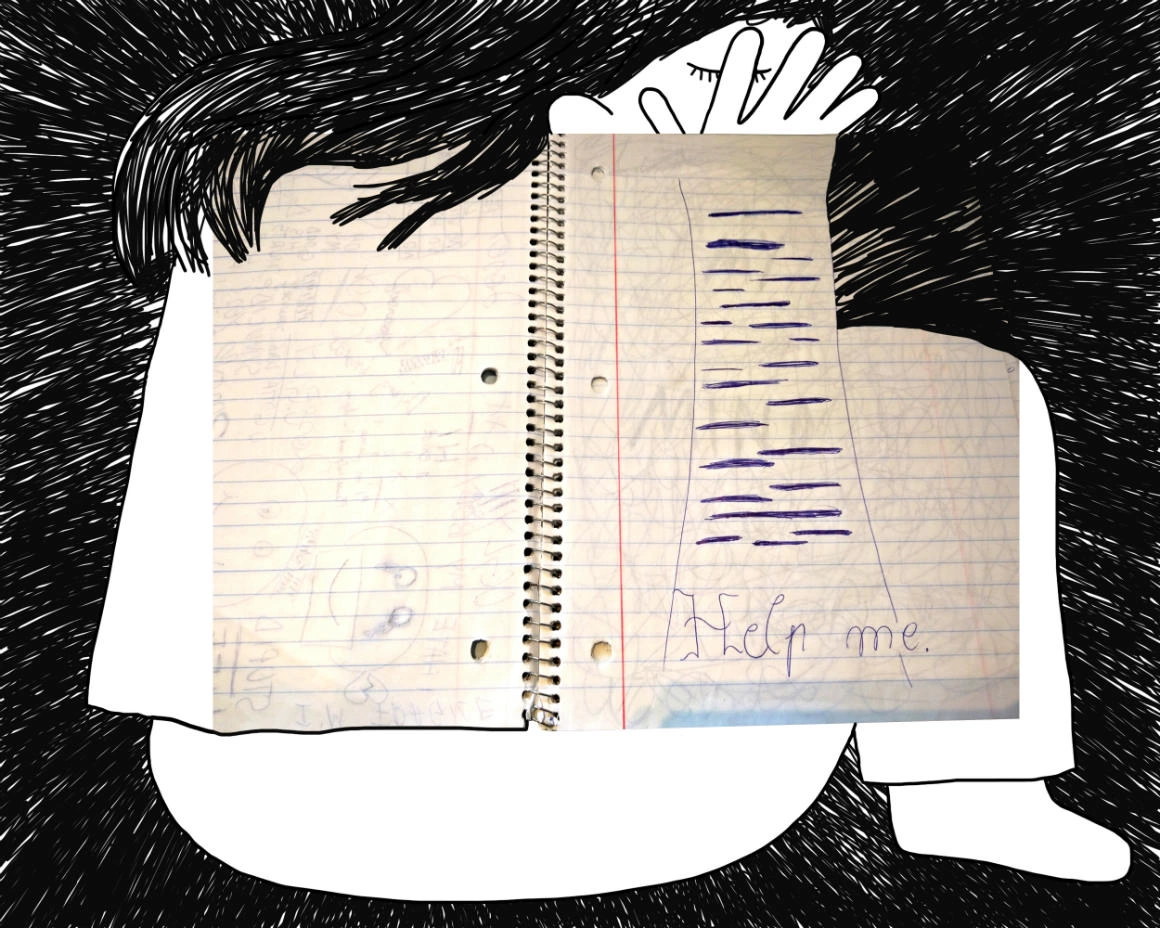

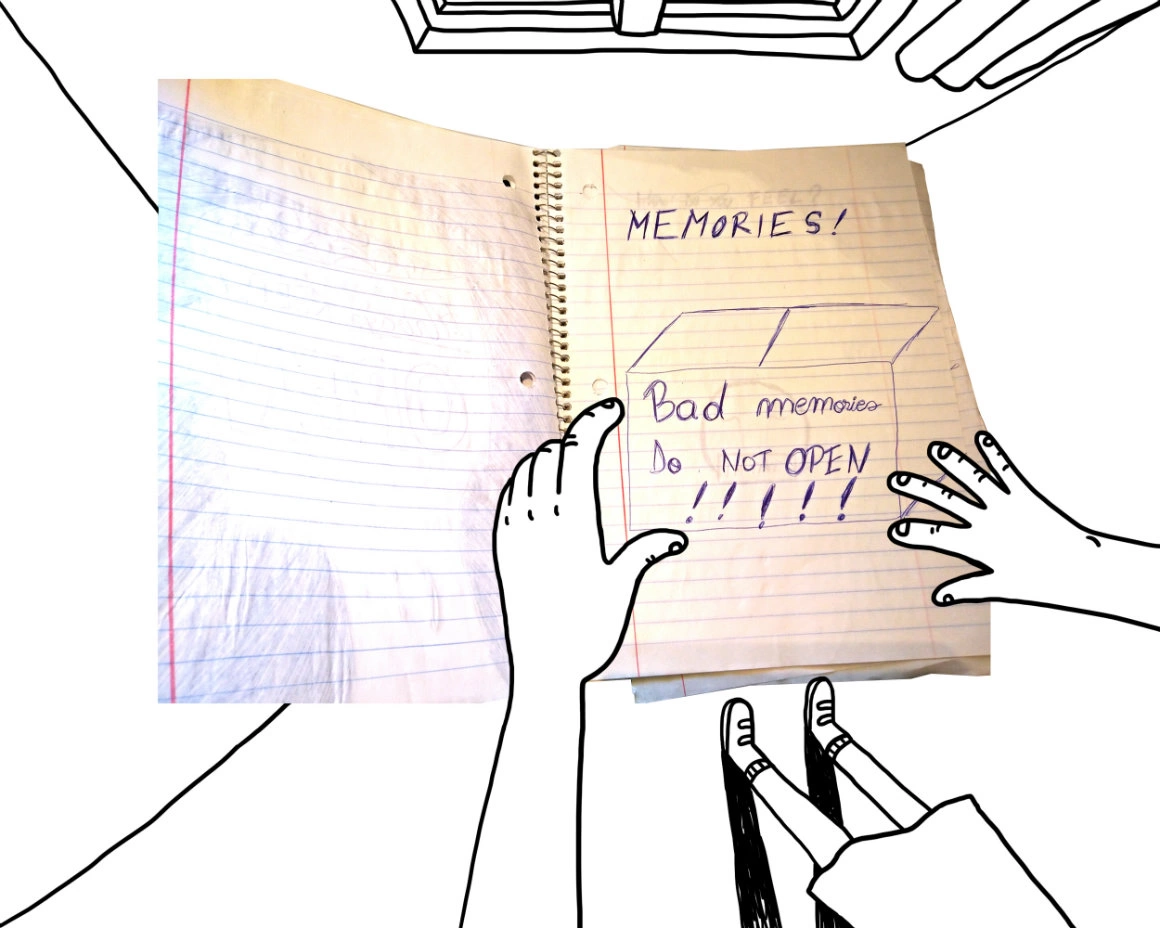

“At first, I used to walk her to school every day, until the class teacher told me to let her do it alone”, Dana’s mother remembers. She started being more careful with her, to communicate more, and to spend time together. She discovered a journal with Dana’s drawings, from the time she was being bullied by her classmates. “My little girl was a wreck from all that humiliation. She thought she was useless and ugly”, the woman confessed.

To try and recover from all that abuse, Dana spent 6 months in therapy. She was only 13. The librarian from the new school helped her deal with things. So did the friends she made at her new school.

I started documenting this issue last year, after one of my best friends from high school, Cristina, reminded me of an episode I had completely forgotten about. “Ha-ha, you were crying your eyes out when I got to the locker room, after gym”, she told me over a glass of wine, one evening. “What?”, I said, filled with surprise. “How? When did this happen?” I remembered absolutely nothing.

Cristina started telling me about it, and that evening I was 16 all over again.

I was in the girls’ locker room, when two classmates jumped me. “Everybody in this classroom hates you!” they yelled at me. I was sitting on one of those long, wooden desks and there was a wall behind me and on the hanger above, the girls’ change of clothes. I drowned in it.

“You’re arrogant and heartless! You think you’re the smartest, but you’re stupid! A stupid nerd with no life”, they continued.

In high school, there were mostly girls in my classroom. It was true, I was a competitive nerd, who didn’t let anyone copy from her, and because of that, I didn’t have too many friends. My classmates despised me. They called me names, mocked me.

When I asked the two girls to leave me alone, they screamed at me even louder. “You don’t have any friends. So, you have big grades! Big deal! Do you think those will get you far?”

At the end of the class, when my friend Cristina entered the locker room, my face was red from all the crying, and my eyes were swollen. She god mad, took the girls outside and started a fight with them. Cristina had a tough cousin, a trouble maker, and the whole city knew him. I think he was mentioned in that conversation.

Ever since that evening, I asked myself why I had forgotten about this episode. I deleted it from my memory, the same way I would clear the blackboard in the classroom. I forgot all of the names I’d been called in high school, all the parties I wasn’t invited to, and how I was spat at. About all the breaks I used to spend on my own, and about the psychology class when I crossed the classroom and one of my classmates told me I was so mean, that I could “walk over dead bodies” to reach my goal. I didn’t understand what she meant, but I felt awful. The trip to my own seat lasted a week.

I hated that time of my life so badly, that I decided to leave Moldova.

After I wrote about this on Facebook, I launched a type of call to arms. I wanted to talk to as many people who had lived through similar experiences in their childhood or teen years. The following weeks, I received dozens of emails, and some of them were really hard to read.

-

“My classmates were laughing at me for two reasons: I had excessive body hair and trouble hearing. In high school, they would whisper mean things to me, to see if I could hear them. I’ve become a withdrawn person who likes to keep to themselves.”

-

“At 16 I weighed 86 kilograms. A fatty makes the perfect punching bag, don’t they? Four boys from my classroom would kick me in the back, pull my pants down and call me fatso, butterball, or stuff like that. In the first six years of school, I would get at least four beatings a day. My name was Mayo.”

-

“In school, they called me «cheese» and «whale». I went on a lot of dangerous diets, and felt like a pariah for many years. I felt like someone who had to make huge efforts to fit in, simply because I was esthetically incorrect.”

-

“When I was born, one of the nurses wrapped me the wrong way and my left ear got pinned to my face. At home, my mom saw this and try to reposition it. She managed to do it, but my ear is still sticking out a bit. This was a big subject of amusement for my male classmates. It marked me so much that even now, after one year of relationship with a boy who’s turned out to be the love of my life, I’ve still not managed to muster up some courage to tell him about this. He’s never seen me with my hair up in a ponytail.”

-

“The abuse started around the 9th grade and went on for two years. I’ve went through the whole nine yards: swears, name calling, public beatings (beaten and kicked), humiliations, you name it. I had asked myself many times: « if I were to disappear, would anyone notice? »”

-

“I was bullied because of my nationality. I’m Hungarian, and this made my classmates offend my parents, my origins, and my rights. I started avoiding the recess, and public places would terrify me. During elections, my classmates would even attack me during class. They would tell me I had no right to talk in this country. That all «bozgors» need to be put on one stadium and be executed. I felt horrible and I made use of force many times. To protect myself, I became a bully.”

-

“The chief harasser was the teacher herself, who managed to turn all the students against those who, like myself, couldn’t afford to buy her presents, Mărțișoare, and expensive flowers. School was hell for me. My discrepant social status manifested itself not just in my ragged clothing, but also in my grades and the way the teacher treated me. Aside from the usual beatings (ruler over the palm, ears pulled, smacks), I was told I was the most stupid, laziest, and dirtiest student. I was the one who needed to be isolated from and hated by the others. I started getting bad grades and I slowly became an embarrassment to my family. My mom genuinely believed that I had a learning disability and she took me to a psychologist to get tested, and did a CAT scan on me to see if I had a brain tumor.

Dana and Matei are 17, and 18 years of age, respectively. They’re attending new schools, where they feel alright. They have friends, brave expressions, rosy cheeks, and are armed with strong words.

The psychologist who worked with Dana taught her not to listen to all the noise around her. “What I feel is much more important than the opinions of those around me”, the teenager says. At her current school, the counsellor is a constant presence in the lives of students. They know everything that’s going on, every single drama, teen crush, and who’s fighting with whom.

You can still see the cutting scars on her arm.

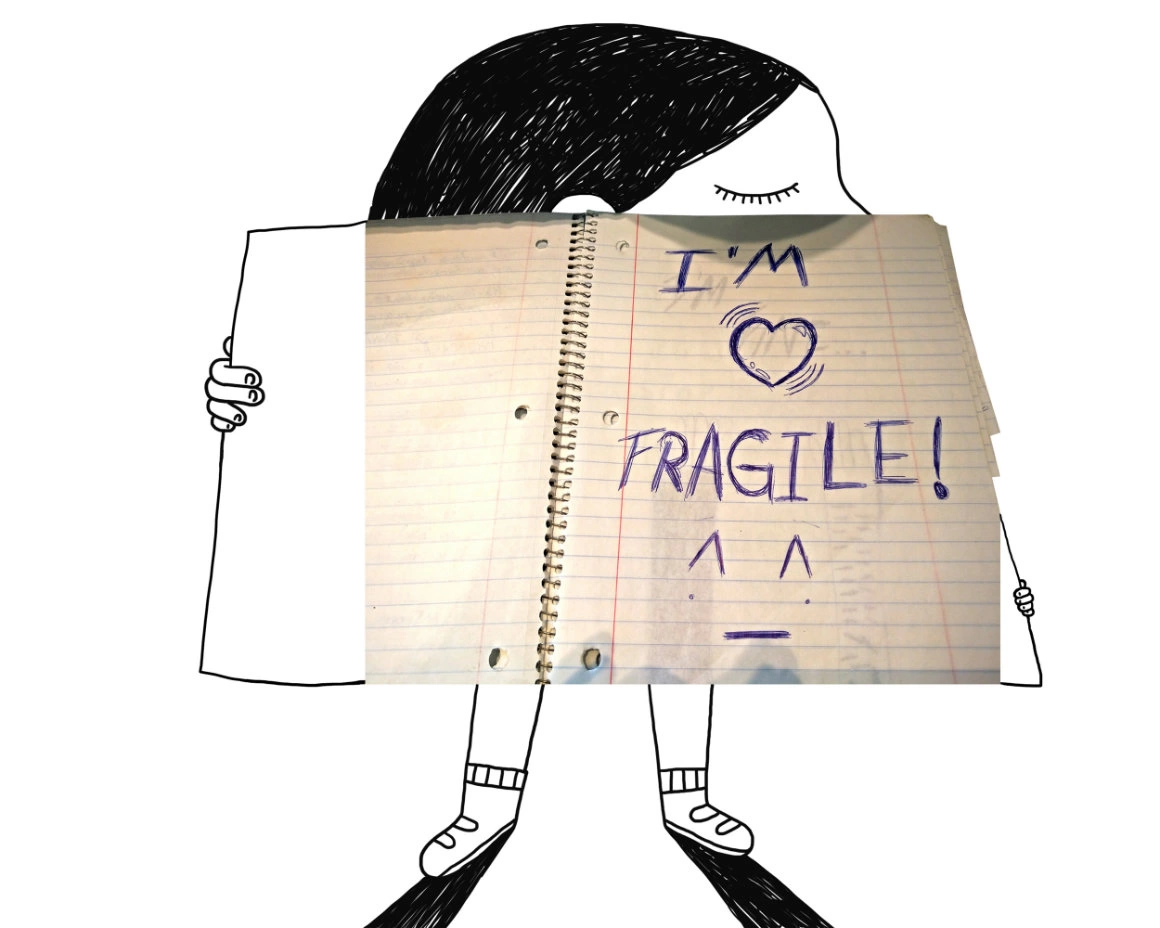

* The names of Dana’s classmates are pseudonyms. Illustrations by Sorina Vazelina, using pages from Dana’s personal journal.

* Romanian children who suffer bullying or other forms of abuse can call the The Child’s Telephone 116 111, where they can get specialized help from psychologists and social workers.

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea.

For more fresh English-language cultural journalism, brought to you by the new voices of Romania, look here.