Romanian peasant, Orthodox Christian and Gay. Cristi Marcu, a cantor for 20 years at the church, could check all three boxes before learning he must give up one of them.

I can see Cristi Marcu through the van’s dirty window pulling into the bus terminal in Cluj-Napoca. He waits on the platform with his hands in his pockets as people bustle around him with their luggage or stand in line at Fornetti to get food for the road. He’s a large man, bearded and balding. His face is round and childish. We’ve never met before, but we hug like old friends.

The plan is to go to Sălicea, a village near Cluj, where he lives with his grandma. On the way, we stop at the former Libertatea furniture factory, a part of which now operates as a gym. A young man comes out of the building with a playful smile. He plucks a dandelion out of the grass, holds it up to Cristi, and hugs him. How’s it going, Badger? It’s his boyfriend, Paul Mureșan, one of Romania’s major young illustrators. I got you some gardening gloves, Cristi says. Today they’re planting onion, carrot and parsnip in the garden, radish and spinach in the greenhouse.

“The whole village knows, not just my family,” Cristi says about their relationship. “After 35 years of being kind of homophobic, I would say.”

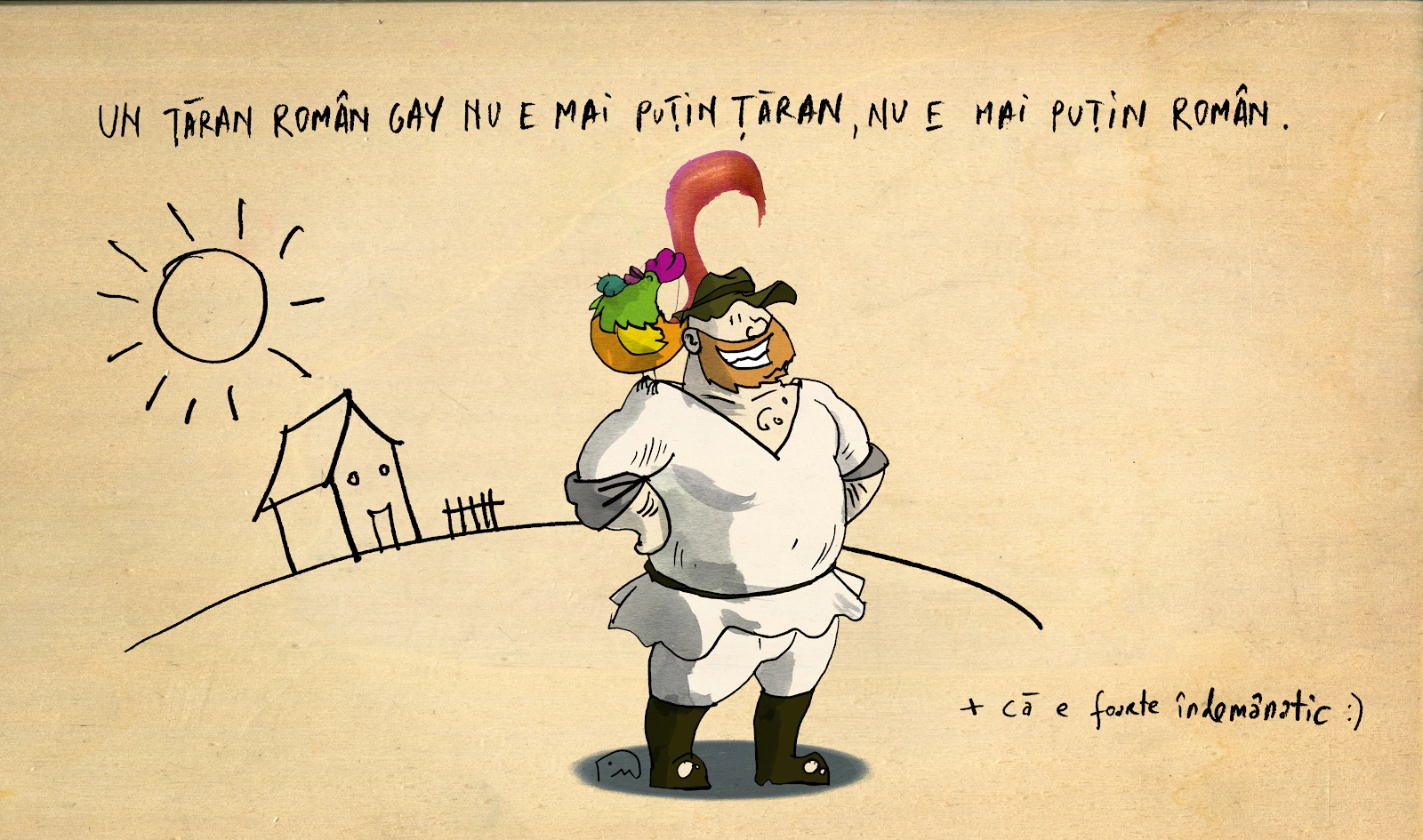

Paul did an illustration inspired by Cristi after the protests at the Romanian Peasant Museum against the screening of Soldiers. Story from Ferentari, a film about the love story between two men. The protestors argued that the Romanian Peasant Museum is a sacred space and that homosexuality doesn’t exist in Romanian villages. Paul’s drawing portrays a manly man, dressed in traditional peasant’s clothing, a rooster on his right shoulder, with the words “A gay Romanian peasant isn’t less of a peasant, isn’t less of a Romanian.”

All three of us get in the car and head to Sălicea. We drive by the newly built villas on the outskirts of Cluj under the perfect blue of an April sky. We arrive at the village in fifteen minutes and Cristi parks the car next to a village store to do some shopping. The church is just across the road where he sang at the lectern for 20 years.

Why?

Cristi’s grandmother used to be the cantor at their village church, and he took over her role when he was 14-15 years old. He was a sort of choir leader, first in one village, then in two. As a pillar of the church, he accompanied the priest for all of his important activities—they had Easter meal together, they were like a family. Cristi tried to convince his neighbors and friends to go to church and to be more religious.

He knew he was attracted to guys by the time he was 11 or 12, but didn’t tell anyone about it. He thought what he was feeling was an abomination, something unhealthy, not right, not good. As a teenager, he tried having relationships with girls and when they failed he gave up looking for any kind of intimacy. He didn’t know LGBT people. His only contact with the gay community came through films and then through discussions he had on the internet, during the mIRC days. By the time he was 35, he’d had three or four sexual encounters which he’d considered slip ups. He was ashamed of them. He would tell himself, “I slipped up, I messed up, that’s it. We’ll start over again.” In his circle of friends, he made gay jokes to avoid any suspicion.

He grew up in Cluj-Napoca, but moved to the countryside at 23 to get away from family troubles and a dad who had problems with alcohol. He started renovating the house, raising the animals, planting vegetables and flowers. In 2005, his mother got sick and he took care of her. His life kept him busy externally, and kept his internal problems at a distance. But he gradually began to feel that he was trapped in a despair he couldn’t get out of, summed up in one word: why. Why should he go on?

“I think about the last ten years of my life a lot. The period between 2008 and 2015 is blank. I did absolutely nothing. I survived and that’s it. I was slowly, slowly dying those days. The flowers are a good way to measure it. 15 years ago, there wasn’t a lady of the house in the whole village who had flowers like mine. And it got to the point that I had no flowers at all. I’ve always loved flowers. Some survived in the garden but in the pots, everything died. I didn’t take care of them anymore, I didn’t have any more energy.”

Then something unexpected happened.

On the morning of September 1st 2015, Cristi woke up to an extremely lucid thought: I’m not alone. He was at a party the night before where a friend he hadn’t talked to for years came out to him.

“I just realized that I wasn’t alone. I thought about it a lot. I can’t think of a very clear explanation, but it was basically the thought that I’m not alone. I’m not alone. Look. Someone I know is going through the same thing. And it’s ok. It’s not the end of the world. I guess I saw him as a person I could stand shoulder to shoulder with.”

The thought kept snowballing as, one day after the other, he started accepting himself as he is. He was 35 years old and he hadn’t had a single relationship. “At that point, I made peace with God, saying in my prayers, Lord, this is how you made me. This is it. And I joke with Paul about it, September 1st 2015 is pretty much the day I was born again.”

The Stork Chick

Four cats play in the yard of Cristi’s house, their fur warmed in the sun. His grandma is outside, stretching over a bench. Her name is Ana and she’s 88 years old. The TV in the background is on Trinitas TV—we shall forgive all for the Resurrection.

Paul changes into work clothes, plays an Arcade Fire song on his phone, then goes to the garden and starts digging ditches for seeds. After focusing on drawings and heavy subjects for days on end, it’s a relief to work with the earth. He recently finished an animation about the fear of death, which included nearly 10,000 illustrations. It was also through an animation that he came out to his parents.

Cristi shows me around the property: the house, the well, his carpentry workshop where he recently built the setting for the play 3milioane (3million) about the petitioning efforts to change the definition of a family in the Constitution. Then we sit down to talk under a tree. On the table next to us, there are bunches of the parsnip they planted last year. They stayed in the ground through winter and he pulled them out now. Some of them shriveled a little, but most of them held out beautifully against the cold months. “There is no more why,” Cristi says watching Paul, working. “I’m so glad he likes it here.”

Cristi couldn’t go back to Cluj. He realized that at the end of winter. He went out to clean up the yard, take care of the trees. He felt he’d gotten a hold on life.

The only stork’s nest in the entire village is in his yard. It’s about 15 years old. The storks toss out their chicks sometimes and, one year, Cristi saved a chick that had fallen into the lilacs under the nest. He was renovating the house with a craftsman from Sălicea and the neighbor took the chick to his house. Together, they took care of it, fed it frogs, insects and fish from the priest’s pond, they taught it to fly. It became the village pet. Then, one morning, the stork woke up more agitated than usual. It walked around a bit on the roof, then flew away.

Penance

In the months immediately following his revelation in September 2015, Cristi tried to reconcile the two worlds that had been silently grinding against one another inside him for years: his faith and his sexuality. He was still singing in church but he started discussing his sexuality with his family, close friends, and people in the village.

Sometime around the end of January 2016, he went to the priest in the village, a person he’d considered a very close friend for the last 20 years. He told him he was depressed, and the priest sent him to a confessor. “Pray, don’t give up on yourself. That was the message the confessor and the village priest had for me. Meaning don’t do anything that would resemble the life of a gay man. Don’t have sex, don’t do anything related it. Live a life of chastity. The church still considers homosexuality an illness and, what’s more, they consider it curable.”

The thought that hurt him most was that he should live life alone, without any affection.

The confessor had him say prayers including The Prayer of Penance. I, the unworthy sinner, I am not worthy of your love. A week later, he went back to confess. He was relieved for a few hours, but then he felt like he’d fallen into an even larger abyss. The following week, he cried almost continuously, with nowhere to turn. He started taking Xanax to ease the depression.

Then, in March he went to his brother’s place for a week in Cluj. He clearly remembers the evening when he knew he had to make a choice. “I was in bed and I told myself, ok, I have to give up one of the two. I can’t give myself up. And I didn’t need to tell myself, ok, I’ll give up church because—even if it sounds strange—I could feel something was already falling apart in me somehow.”

The next week, he started coming out of his depressive state, but he also was experiencing a kind of freedom that he didn’t yet know how to process. He lost the cornerstone of his identity, the church. “For some months I felt like a piece of cloth that had nothing to hang on to.”

He had a talk with the priest in the village. Cristi asked him what was Jesus’s most important commandment, and the priest responded: Thou shalt love thy neighbor. Cristi told him that this isn’t the whole commandment. “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. The most powerful part of the commandment is as thyself. You ignore that. You don’t teach people to love themselves, you teach them to hate themselves. And so, if I was taught from a young age to hate myself, to hate what I feel and, effectively, hate myself, what love can I give to someone else if I have no love for myself?”

He told the priest that he felt abandoned by him. “I just needed you to put your robe aside for five minutes and ask me What’s going on? How are you? I started to cry. He felt it, too—that he didn’t do something and he should have. I told him: I really felt your absence. But it was no use. The demands of the job are so much that he can’t stop it.”

He wanted to see a priest who would reassure him, what the hell, there’s nothing wrong, you’re fine. Right after going to therapy, he realized a priest couldn’t truly help him. “Because right when I’d find the priest to say it, he’d be outside the church framework. And I realized that, in my case, I needed validation from the entire Orthodox church. And I thought what the hell, are you stupid? You want to change the church? I mean, I never was a half believer. I was a believer. And then the burden was even heavier.”

The Pill

The theory underlying conversion therapy is the claim that homosexuality is an illness that can be cured, usually through faith or sexual abstinence. This is what the priest and the confessor suggested for Cristi.

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) decided that therapies to change sexual orientation lack medical justification and threaten health. “Since homosexuality is not a disorder or a disease, it does not require a cure,” said Mirta Roses Periago, the former director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

In a quick Google search of the word homosexualitate (homosexuality), the first results take you to sites that present homosexuality as a treatable disease. If you’re a young person with questions about his or her sexuality, or a mother trying to get her head around the sexual orientation of her child, you’re going to read that homosexuality can be treated, that the highest percentages of mental diseases are among homosexuals and that most pedophiles are homosexual.

Some of these sites are directly or indirectly related to Coaliția pentru Familie (Coalition for Family).

The first page that appears in the search is the site homosexualitate.ro, which promises “A Hope and a Cure for Homosexuals.” It offers information about reducing and eliminating “same sex attraction, confessions of people who succeeded and comments and analyses of social norms.” The former IP address of the site also hosted the webpages Coalition for Family, PRO VITA Bucharest and Cultura Vieții (Life Culture).

Still on the first page of the Google search, there’s an article called “10 myths about homosexuality” published on activenews.ro. The article was taken from the book, Fața Nevăzută a Homosexualității (The Unseen Face of Homosexuality), by Virgiliu Gheorghe and Andrei Dîrlău, published by Christiana publishing house, owned by Pavel Chirilă, a member of the Initiative Committee for the Coalition for Family. The book aims to help “people oppressed by the engulfing passion of homosexuality to realize that there is a way back to normalcy” and to make us aware that “homosexual propaganda represents the greatest assault on the human race in all of history.”

The books co-author, Virgiliu Gheorghe, is a specialist in bioethics, in the "destructive effects of pornography" and in addiction to television. Beyond this, Virgiliu, under his real name, Virgiliu George Vlăescu, is an associate of George Becali with the Imunomedica ProVita SRL company, which supports treating cancer with alternative methods such as oxygen and heat therapy.

One of the main ideas of the book Fața Nevăzută a Homosexualității is that changing sexual orientation is possible. They reference the American psychiatrist Robert Spitzer: “Similarly, Robert Spitzer, a pro-gay psychiatrist, also considered that changing is real and there are no negative consequences. (Spitzer, 2003)” In the book however, an important piece of information was omitted. After retiring, Spitzer acknowledged that his study was flawed, and apologized to the gay community.

If society views homosexuality as a disease, there are those who’d like to “cure” it. Or to “cure” you. 10-15 years ago, Cristi thought that if there were a magic pill that could “rid” you of homosexuality, he’d take it. He wouldn’t have problems with the church anymore, he could have a regular family and he would go back to being a functional person.

After beginning to accept himself in 2015, he pondered the same question. This time, it was clear to him that he wouldn’t take the imaginary pill. “It would have meant giving up on myself, transforming myself into something I’m not. Lying to myself.”

Auntie Anica

One of the first people Cristi told about his sexuality was his 22-year-old niece. It was in the fall of 2015. They went to the mall together in Cluj and, before leaving, she asked what plans he had for the rest of the evening. He said he was meeting someone for pizza and showed her a picture of the guy. He told her he’s gay.

“I was having a panic attack then. I was hyperventilating. And she goes, Are you kidding? I don’t believe you. You don’t believe me? I took her hand and put it on my chest. I think my heart was going at 200 beats per minute.”

Then he talked with the girl’s mother, his older sister. It was a week before Christmas and he remembers that he had to slaughter the poultry. After their mother died in 2005, his sister took over the role of the family matriarch, which made it difficult to tell her. He tried to prepare for her shock. “I was preparing for her to be freaked out. I thought there was no way she wouldn’t freak out. And when I told her, I got freaked out because she wasn’t freaked out.” She asked him if it would have been easier if their mother hadn’t died. Then, she suggested he not tell anyone else. “I told her not to worry, I wasn’t going to commit social suicide. But things went on differently. I didn’t commit social suicide, but I talked to people about it.”

In the same period, he went to Auntie Anica’s for coffee, a neighbor of his, over 60 years old. She asked him what was going on with him because he seemed down. “You know we can talk about anything.” And he worked up the courage to tell her he was gay. She was shocked at first, but also curious. They talked for several hours. “And at one point during the discussion, she said, Well, I think I’ll love the person you’ll be as much I love you now. Obviously, I started crying on the spot.”

Cristi gradually widened the circle of people he spoke to about his sexuality. He told the story to two or three people in the village whom he knew would spread the word like wild fire. A few days later, the whole village knew. A few people asked him over Facebook if it’s true. He confirmed that it is and he invited them to talk with him.

“I didn’t talk to the whole village about it, but I talked with anyone who was curious enough to ask, people I could see were somehow curious,” Cristi says.

The Green Egg

“Cristi, I have some wood here,” calls his neighbor Dan, a 70-year-old man with a kind voice. “I’ll take it. Can you throw it over?” There’s a blooming wax cherry tree in the middle of Dan’s yard, shining in the afternoon light. “Thank you,” Cristi calls back.

After Paul finishes pulling weeds and digging up the soil for seeds, Cristi puts the food on the table. He brings rice with vegetables, grilled meat and green onion. While we eat, Paul is reminded of a story. He was riding in a taxi and there was news about the referendum on the radio. “Man, these guys aren’t normal. They’re sick. It’s not ok,” the taxi driver said about gay people. “That’s interesting, man. Why do you say that?”, Paul responded, curious. “I don’t know, man, it just isn’t normal. Just think about it. Don’t you have a girlfriend, man, you tell me, how could you…?” Paul said he doesn’t have a girlfriend, he has a boyfriend. The man was caught a little off-guard, then he added: “Hey, man, that’s cool, you’re not hurting nobody.”

The change in reaction didn’t surprise Paul. “We learn a lot from these human interactions with the neighbor, the taxi driver, with someone at the gym when you talk. Because you can see there’s a person there, behind these theories.”

The mentality would change much faster if everyone was more active where they lived and with the people they interacted with, Cristi explains over the sound of Dan’s roosters crowing in the background. You can do the best work right where you are, talking with people as equals. “I had a few skirmishes online with different Facebook friends that I also know in real life. And the moment we got face to face, when they were met with humanity, they were disarmed.”

Cristi believes that any time you see that a person is curious—even if it’s in a negative way—it’s important to let the person be curious. Because he isn’t angry at you. He’s angry at himself because he doesn’t understand. Although Cristi is no longer religious, he is still spiritual. He believes that all philosophies on earth are somehow pieces to a puzzle.

“Because no meaningful ecumenism exists, the puzzle pieces don’t come together to make something. If you take any divinity and strip it of dogma, laws, organization, and whatever else, you’ll arrive at the essence. You’ll find just one thing that can be defined in a word. Love. Unconditional. Love that we owe to one another but, most importantly, love for ourselves. And I realized that fighting, being hostile, being aggressive, fighting for your rights at all costs, physically fighting, you don’t get very far. Your own hostility comes paired with the hostility of the other. But when you’re assertive, and you show the person, hey, I’m a loving person and I want to learn to love myself so I can then love you, when you show the person humanity, he can calm down. He starts thinking about it. As long as the person is hostile and his survival instinct is switched on, he can’t be rational.”

After we finish eating, Cristi goes inside to get dessert: crepes with plum and apple jam. His neighbor Dan calls him again from over the fence. Cristi doesn’t hear him so he calls for Paul.

“Come here, Paul. I have something for you.” I go with Paul to take the present. Some small hen eggs. One of them is greenish. “You ever seen a green egg?” the neighbor asks, smiling.

Grandma

Over the last two years, Cristi came to feel comfortable in his village—comfortable enough to have Paul come to visit. “Ok, not completely comfortable. There’s always a part of me that’s on guard. But it’s 100 times better than I could ever have imagined.”

The decision to talk as openly as possible about himself was a practical one. Two years ago, he came to the firm decision that he wanted to find someone to live with him in the Sălicea house. But for this, he could no longer keep his sexuality hidden from the people around him, his family and neighbors.

One of the most difficult times was talking to his grandma, a religious woman, 88 years-old. “She’s the person most responsible for my education and for that of my siblings. She’s a pessimist, she’s good, but she isn’t tender. She was always a strong woman, a woman that liked organization and cleanliness. She was a person who suffered her share. Her first child died when he was eight. The second, my mom, at 55. She’s a woman who, I’d say, I got a long with pretty well.”

He told her he was gay and that he wanted, at some point, to find someone to share his life with. It wasn’t necessarily easy, but she gradually came to accept it. When I tell Cristi that it must have taken a lot courage to do that, he quickly responds: “To me it seems she was the courageous one—to accept and to understand. I think it’s courageous of her to accept Paul.”

While Cristi and Paul work in the garden, Grandma eats beef salad on a bench outside. The cats gather at her feet and she jokes with them: “I fed you yesterday.” She asks where I’m from, what my parents’ names are, if I came all the way from Bucharest with those ripped jeans. She has pains in her bones so she can’t go to church anymore. “I miss the people, but that’s over now.” Then she looks at the two of them digging and says: “[Cristi] was depressed. But he’s been really happy since being with that boy.”

Night gradually falls over the village. A stork comes back to the nest carrying some branches in its beak. Several sparrows stir alongside the stork. “One of the secrets to keeping that nest together is that the sparrows make their nests inside it. It’s basically an armor,” Cristi explains.

“I feel extremely lucky to have people around who accept me, to have had the strength to take that step, to have been aware that I needed therapy.” He also wants to help in the future so he’s enrolled as a student at the Faculty of Psychology in Cluj. He’s in his second year.

We gather around the bench, Cristi sitting next to his grandma, and Paul on a chair. “Cristi, whose house is that with two stories?” “Which one, old lady?” he asks her kindly and puts his arm over her shoulders. I look at them from a distance and they debate over who owns the house for the next half an hour. They’re both completely convinced that they know everything that goes on in Sălicea—the village where Grandma’s lived for 88 years, and the grandson for 15. And all the years ahead.

Translated by Andrew Davidson-Novosivschei