In August we had the chance to see and take part in several dozens events at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, one of the biggest of its kind in the world. Founded in 1983 and becoming an annual event in 1997, the EIBF hosted around 900 writers from more than 55 countries at the 2018 edition, totaling almost 800 events in 17 days. Unlike other festivals we are familiar with, EIBF doesn’t just bring together well-acclaimed writers and artist and then organize events for them, but rather the other way around. That is they pick a series of themes and guest selectors, and invite authors whose fields of interest are related to that theme or who are known for approaching certain topics in the same area of interest as the chosen theme.

Besides having Freedom as a general theme, the festival had four individual selectors and a collective one for five different themes: Adele Patrick, Lifelong Learning and Creative Development Manager at Glasgow Women's Library. (Revolting Women), the Greek economist, academic and politician Yanis Varoufakis (Killing Democracy?), Afua Hirsch, British writer and broadcaster (Identity Papers), Ehsan Abdollahi (Illustrator in Residence), artist Tania Kovats (The Sea Around Us), Young Programmers (Year of Young People: Codename F). Because just preaching equality and diversity is never enough for such a big event, the geographical cover of the guests’ countries of origin looks like this.

Everything from how the space looked to the baby blue sweatshirts all the staff members wore was so new to us. In Romania, the largest literary gatherings are generally organized as book fairs. The two best known and most attended are, of course, Bookfest and Gaudeamus, held in Bucharest. This means that most publishing houses rent a display space from the organizers and hold events presenting their recent publications. By their own nature, fairs are cost-oriented rather than reader-oriented, that is they are at their core designed to popularize and sell books, not to create a proper environment for the interaction between author and reader or for the debating of relevant socio-cultural issues and trends.

Thus they have a quasi non-existent international component, although there are some international writers present at every edition, with a single guest country usually participating. Such an approach tried to be counterbalanced by the emergence, in the past 15-20 years, of a few international literary festivals, most notably FILIT (Iași), FILB (București), FILTM (Timișoara), but also of some dedicated strictly to poetry, such as FIPB (București), Poezia e la Bistrița or Poets in Transylvania (Sibiu). These festivals include series of readings, workshops, dialogues and debates, focusing visibly more on the authors, readers, and the author-reader relationship, trying to access new audiences and tackle topics of discussion relevant to the world around them.

How to literally build a book festival village

Because 1. The Edinburgh Fringe (the biggest art festival in the world) takes place at the same time and happens at over 500 locations around the capital - so there are really not many places available, if any - and 2. Edinburgh can get so rainy and awful (and WINDY) sometimes, the festival had to take place indoors, have walls and “roofs” everywhere, even though it was August. So not having much choice, they took a public square, called Charlotte Square and they turned it into a little village, with tents that had names and ice cream carts and gin carts (a popular favorite, THANK YOU Edinburgh Gin) and three bookshops and several book signing points and tent destined only for children activities, several coffee carts, and very cozy yurts for authors and the press - conveniently located in the same place so people like us can casually drink coffee around the area pretending that they’re not waiting for Karl Ove Knausgaard to come take his author pic and maybe, just maybe lightly brush against his jacket as he walks by.

Because we’re two and we haven’t been to the same events, we’ll now each talk about what we liked (or didn’t like) most.

Cătălina’s Highlights:

Revolting Women

I think it’s safe to say my favorite events at the Edinburgh International Book Festival were the ones included in the Revolting Women series. This series was an initiative of the Glasgow Women’s Library (a godsend, downright amazing institution if we’re at it, a library/museum that celebrates lives and achievements of women from all over the world, supports women artists, writers and musicians) and it was brought to us by Adele Patrick, the Lifelong Learning and Creative Development Manager at Glasgow Women’s Library. This series was developed to create a platform for women in artistic and academic fields to discuss their role in the society and the challenges and the discrimination they face. It was also centered around Queered Nigerian writing, women of color, women from all walks of life and how they position themselves in their field of work. The first event of this series that I attended was one chaired by blogger and activist Tomiwa Folorunso, with writer and activist Chitra Nagarajan and German-Nigerian writer, speaker and performer Olumide Poopola.

Chitra Nagarajan spoke about She Called Me Woman, a collection of 25 queer short stories from Nigeria, that she edited. Olumide Popoola spoke about her latest book, When We Speak of Nothing, which depicts the life of a trans person who moves from London to Nigeria. The way the events are designed makes it easier to get two sort of different perspectives (although similar at the core) about the same subject. So while Nagarajan’s book has more of an overt approach in speaking about internalized patriarchy and gender in Nigeria, Olumide Poopola’s book kind of integrates queerness into the narrative, normalizing everything. Chitra gave a reading of one of the twenty five stories and it was about this woman who had just had sex with another woman for the first time and it was so long overdue it felt like her brain was going to explode, like she had finally understood why sex feels so good and why it hadn’t for so long and God, her words just made you feel all kinds of happy.

Revolting Women events hold a really special place in my heart and one of my favorite ones was a discussion between Heidi Safia Mirza (British academic, Professor of Race, Faith and Culture at Goldsmiths, University of London), Djamila Ribeiro (Brazilian academic, feminist and philosopher) and Sara Wajid (Head of Engagement at Museum of London), about women of color in the academic space. It really made me understand I knew nothing about this, and that as much as I pride myself on being very informed about this type of things, I did not ever stop to think that for example, all of these words we use, such as multiculturality or just the word “diverse” just eventually become buzzwords that don’t actually do anything for women.

I didn’t realize these women still face blatant discrimination in the work space even when they are invited to, say, conferences or book events that claim to have a “diverse” line-up or an “open” approach to arts and artists. Akwugo Emejulu (author and Professor at The University of Warwick), who chaired the event, even said she gets mixed up with other women of color when she goes to conferences.

Each of them spoke about how people need to detoxify their own academic space and the little steps they themselves do to combat discrimination. For example, Djamila Ribeiro (human rights activist writer and Political Philosophy professor at Universidade Federal de São Paulo) spoke about women of color not being able to explore their own culture in Brazil and how she encourages her students and even fellow professors to stop talking only about American and European feminism, and include more black feminists into their curriculum, such as Audre Lorde or Lélia Gonzalez.

Book events should really feel chill and relaxed sometimes

It was always uplifting to see how many people attended the events, even when they were really early in the morning. I went to another joined event, writers Ottessa Moshfegh (My Year of Rest and Relaxation) and Heidi Sopinka (The Dictionary of Animal Languages) and although it was 10 a.m. on a workday, the room was still full. But I remember looking around me and seeing these two girls who were (judging by the books they brought for signing) Moshfegh fans and were SO genuinely happy to be there, whisper-giggling and never moving her eyes from her. This was one of my favorite events, actually. It just felt like an intimate gathering with friends and I was curious to find out more about the two writers. Heidi had a very unconventional and exciting career path, with her being a cook and a travel writer and a helicopter pilot (yes, VERY cool, I know) prior to becoming a novelist and Ottessa is let’s just say.. your slightly awkward friend who gets distracted quite a bit, but is also so funny and charming and (I really have to say this) wrote “sweet dreams” when she signed my copy of her new book, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which is a book about a woman who decides to sleep continuously for an entire year (wishful thinking for most of us, right? But she’s quite diligent about it.)

Speaking of intimate gatherings, another one I went to was Jenny Landreth’s event, which was actually my first ever EIBF event and it was in this little tent called Writer’s Retreat. I had never heard of her before, but the description of the event really sounded interesting to me, because Jenny Landreth wrote a book about swimming suffragettes. I was immediately smitten with both the book and her, because she was so laid back, so funny, so witty and also because she came up with the word Waterbiography as the description of her book Swell and I like puns more than I care to admit. I decided to buy the book and I also learned surprisingly much (in one hour) about the pioneers of women swimmers and the first types of swimming equipment and about swimming in unconventional spaces.

But the most interesting to me was how everyone seems to have such a personal relationship with water and everyone is so different in that regard and I guess I had never thought about how important this relationship is in defining your existence and you as a person. ”Happy Swimming” wrote Jenny Landreth on my book. She asked me if I’m a swimmer and I said I did swim, but never thought of myself as “a swimmer” and she said I should definitely start doing that, anyone can be a swimmer. So, obviously, now I need to find the closest lido (because Jenny Landreth is into old school swimming places and I figure so should I) and just do some laps like nobody’s watching.

Something I wish also happened in Romania

Obviously I wish all of this happened in Romania as well. But towards the end of the festival I attended the Herland Literary Salon, an event organized on a regular basis at the Glasgow Women’s library, but this was the first time it happened outside the walls of the library and it features young women artists, poets, singers and it was a really fun evening in the Spiegeltent, where there were little round tables covered with burgundy tablecloth and everything looked like an episode of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. The dress code was red and because I am a goodie goodie I really wanted to dress in red and was disappointed to realize I do not own red clothes (I am a beige and brown type of girl, what can I say). I tried to make up for it with red lipstick and a white shirt with red stripes that I normally sleep in and a red beret I just kept in my bag and never wore because it felt too ridiculous and nobody really cared. There was music and spoken word poetry and more music and a quiz and here comes the real reason I mentioned all of this: the team I was in won the quiz and I got a bag of goodies to go with my suffragette crown (every table had paper crowns with suffragette names on them).

On a more serious note, I really wish there was an organization like the Women’s Library in Romania, to support women artists and to organize events like this and the other Revolting Women events. People in Romania still roll their eyes when anyone so much as mentions gender inequality at literary events. A man once told me women should BE literature, not WRITE literature (sidenote: really not something you should say to a woman who offered to give you a lift because it was pouring outside). Of course he thinks that when in Romanian schools children still learn about women as inspiration for writers, women as life partners of writers, women as characters in male-authored novels (even then, mostly because it helps build a stronger male character), but almost never about women as writers.

Vlad’s Highlights:

The World Around Us

I will start with my personal non-fiction favorites, because the EIBF hosts a great amount of events with academics, scientists, artists, journalists, cooks, etc. & doesn’t focus only on fiction writing. For instance, the first talk I attended was between Anne Applebaum, professor at London School of Economics and Columnist at the Washington Post, and Allan Little, former BBC reporter and correspondent to, among others, Moscow in the last two years of the Yeltsin presidency. The discussion revolved around Applebaum’s most recent book, Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, that analyzes the Ukrainain famine of 1932-1933, also known as Holodomor, during which (according to Applebaum’s sources) around four million people died of starvation.

The premise was one that resonates rather unpleasantly with, for instance, some of the public discourse in today’s Romania: peasants were seen as “unnecessary class standing in the way of evolution”, so Stalin decided to simply have all their food confiscated in order to “feed the cities”. In the end, as Anne Applebaum emphatically put it, “just being alive arose suspicion”, because peasants were not supposed to have anything to eat. It was a compelling and strangely contemporaneous evocation on behalf of the American-Polish journalist, because she referred to the peasants as a social class that have been constantly dehumanized for more than a decade before the actual genocide took place. Obviously made me think about the current dehumanization of certain social categories by others (and sometimes the other way around), and of course, again, about the incredibly violent and murderous policies of Communism that seem to be simply brushed under the rug by a series of contemporary Marxist thinkers.

Speaking of Marxism, there was actually one event dedicated to Marx’s 200th anniversary, with the participation of historian Gregory Claeys and literary theorist Terry Eagleton. I went and it was a peculiar feeling. On one hand, you know you have in front of you acknowledged scholars, widely published and respected authors, who raise legitimate subjects such as work poverty and the threat of the world ending because of environmental issues. On the other hand, you have them talking about China as a Marxist “success story” (in terms of what, exactly? Clearly not human rights - so what are we really talking about then - just the economy? Because Yan Lianke talked about his books being banned & how hard it is for him to find a publisher in China a few days later) and about how Marx “remains a democrat, while Lenin departs from that model” (well, at least Lenin is not a “success story”), among others. I had ambivalent thoughts during the event. Like now they’re talking about something I completely agree with and see and understand and two seconds after that they start saying stuff that seems like complete nonsense to me. Quote of the event: “Marxism is about freeing us from work” (Terry Eagleton).

Moving from China to its neighbor whose human-rights record is arguably worse, North Korea. There was a dialogue dedicated to North Korea as well, or, more so, to the journey through North Korea that Canadian author Rory MacLean and British photographer Nick Danziger took. I won’t repeat here all the things we know about how North Korea works, I’ll just mention something I didn’t know before the event that struck me as strange: the country’s citizens required to keep an every day diary in which they, besides describing daily life, have to self-criticize and mention any “wrong” things done by their closed ones. This probably makes North Korea the biggest producer of fake-diaries/memoirs in the world.

Of course each and every one of these events at some point touched on Trump or Putin or Brexit, and the escalation of verbal and physical violence in public discourse, and perhaps historian David Andress best characterized the state we’re in as “cultural dementia”. We forget what we don’t like, remembering only what we do or what suits our own purposes or confirms our misconceptions.

Overall I would describe the non-fiction selection of the EIBF as very broad and encompassing. From gender studies to sports to music to business to politics, they touched an extraordinary amount of themes and interests, so it’s no wonder that I have never seen less than 30-40 people at any event. There were plenty for everyone’s taste (letter of advice to Romanian event hosts: it doesn’t have to be critically praised fiction for its author to make it to a festival). Mind you, they were ticketed events with prices ranging from 8 to 10 pounds. The only two talks that we wanted to get in and couldn’t (because they sold out way too quickly) were Yanis Varoufakis’ talk with the Leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn; and Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish First Minister, speaking to Ali Smith about her books. Imagine the Romanian Prime Minister speaking to any contemporary writer about their books. Yeah, that’s what I thought. Or leading the Pride:

Proud to lead this massive @prideglasgow march today - celebrating and reaffirming the values of tolerance, diversity, equality, love and respect. #chooselove #pride pic.twitter.com/kTgVnDlJMk

— Nicola Sturgeon (@NicolaSturgeon) July 14, 2018

A Guide for Absurd Reality

Maria (Masha) Alyokhina is one of the original members of Russian protest punk group Pussy Riot. She was in Edinburgh to talk to Yanis Varoufakis about her newly published book, Riot Days. They didn’t let her fly out of the country, because they threw paper planes at the FSB (the former KGB) Headquarters in Moscow and she was supposed to be “on probation”, so she illegally did it anyway (and came to Edinburgh by car). For some context, the story of Pussy Riot began in 2012, when five members of the band improvised a concert/performance in Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. Two of them, Masha and Nadya (Nadezhda Tolokonnikova) were sent to jail for two years because of that. This is actually what the memoir’s about, the first protests and being incarcerated (actually working in a camp for 12h daily and receiving somewhere between 2-3$ a month for that work). It’s the same group that protests for LGBT rights in Russia and who invaded the pitch at the World Cup Final this year.

But what struck me about her, more than the book, which I’ve read since, was that she’s really a natural. Whatever Varoufakis (in his own weirdly pretentious and sometimes self-centered manner) threw her way, she came up with something that we all should remember. Asked how it all started, she replied “I didn’t want to be an activist; [...] I’m just a girl who decided to do something”. Asked if she was afraid, she replied “if the fears grow, make fun of them”. Asked a question with a lot of conditionals in it, she replied “if, if, if, I don’t like these ifs”. Asked about “the economic view of Pussy Riot” (really?!), she replied that “the question of economy is not for a country who works against its people physically”. Also, for other Eastern European countries, and also for us at the moment, the fact that “what was a scandal six years ago happens now every day” in Russia should really make us think of how authoritarian regimes work their way and slowly take rights away from us. Varoufakis at some point said we’re in the presence “of a real hero”, but Masha looked at him like he should know better. To quote an art piece at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, “There will be no miracles here.”

I absolutely have to talk about the literary sensation of the moment in Romania and arguably the headliner of the festival: Karl Ove Knausgaard. Presenting the sixth and final installment of the My Struggle series, Knausgaard was his usual articulate and composed self, charmingly navigating through questions. Of course, at some point, after your books become an “international phenomenon”, the questions you get from your interlocutors and the audience get repetitive. So here’s what I’ve learned: 1. No, he doesn’t remember all the details in the books. They are made up; 2. Yes, it’s a novel exactly because those things are made up; 3. No, he didn’t let himself think of any consequences of writing so much about real people in his life while writing the books; 4. No, he doesn’t talk about his life, he uses his life to talk about other things - painting or literature or shame or Hitler; 5. Yes, he sometimes doubted the memories; 6. He “tried to create a space where something is possible to be said”; 7. Yes, he was afraid of some people in his family’s reaction after the publication of the books. As always with Knausgaard, there’s only one conclusion I keep getting to (has somebody said this before? probably): even when it’s boring, it’s really, really good.

Apparently all the events and books I chose to write about are either non-fictional or clearly deeply connected with real life. Whatever happened to my fondness for fiction?

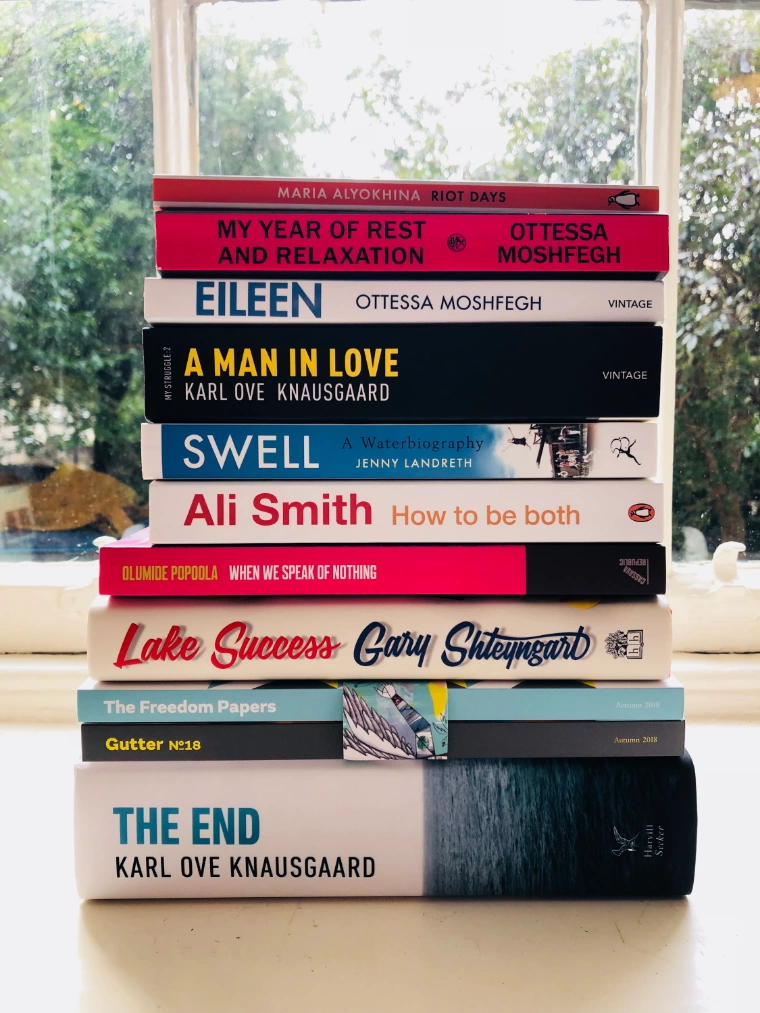

Vlad’s recommendations (or what he would like to translate if he knew all these languages):

Maria Alyokhina - Riot Days

Anne Applebaum - Red Famine. Stalin’s War on Ukraine

Karl Ove Knausgaard - My Struggle Book Six: The End

Ottessa Moshfegh - My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Gary Shteyngart - Lake Success

Dag Solstad - Armand V

Ngugi Wa Thiong’o - Wizard of the Crow

Cătălina’s recommendations (or what she would also like to translate if she knew all these languages, except maybe the second one because have you seen how bloody long it is?)

Maria Alyokhina - Riot Days

Diane Atkinson – Revolting Women

Jenny Landreth - Swell

Ottessa Moshfegh - My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Chitra Nagarajan (ed) - She Called Me Woman

Olumide Popoola - When We Speak of Nothing

Gwendoline Riley - First Love

Instead of an ending, here are some other things we found out about at EIBF and want to share with you:

- one of the tents was called the Spiegeltent and people kept pronouncing it in various different ways and we still aren’t sure what the correct way is

- the only piece of advice Philip Roth gave Gary Shteyngart about writing was: don’t eat butter

- people in Scotland are really fond of queuing and now a queue just feels like home to us

- everyone just loves Muriel Spark

- you can always eat soup and scones somewhere

- people actually buy tickets for book events (lots of them)

- if you go to a Ngugi Wa Thiong’o event, be warned: he speaks in stories - lovely ones nonetheless

- when translators work on books set in places they’ve never been to, they sometimes use Google Maps to “get familiar” with it

- people can actually commit to schedules

- Javier Cercas thinks that “if literature tries to understand the worst things, it is useful”

- Sergio de la Pava thinks “there is something fundamentally violent in America”

- Terry Eagleton says you should tell all your friends you’re a Marxist just to annoy them (if true, this actually explains a lot)

- Dag Solstad really doesn’t think he’d enjoy having dinner with Thomas Bernhard

- The Last Poets are still up and going

- 1 hour is usually enough time spent with any writer (except maybe a few)